|

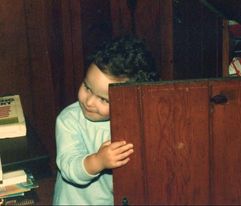

It has been quite a while since I have written an entry to this blog. An immensely sad event has prompted me to return here now. A few days ago, my Sindhi family and our entire circle of acquaintances were shocked by the sudden death of my youngest Sangi sister, Mehak. She died of cardiac arrest on 19 September 2020, following a few months of heart issues that might have been caused or exacerbated by the case of COVID-19 that she contracted earlier in the year. The family had been quietly worrying for her, but no one could have expected such a sudden and tragic outcome. This post is a tribute to a wonderful younger sister, written by the sister who came late into her family, but was nonetheless treated with love from the heart. My sister Mehak was perfectly named, as the word means “fragrance.” Her presence was a gentle one, always calm and pleasing, never brash or bold. What I will always remember first about her is not something concrete, but rather a feeling and a glow that accompanied her presence. She is a difficult subject for writing, because her memory wafts in ideas and colors more than in solid facts or anecdotes. It is often easier to describe her in terms of what she was not; and yet I do not want to give the impression that she was insubstantial as a person. Quite the opposite: she was strong, a person of grit, integrity, deep thought, and compassion. Nonetheless, it is her spirit that seems to me the most vivid aspect of her, and which I hope that these rambling words of mine will evoke in some small measure. In groups, Mehak spoke little, but smiled often. I would not call her shy, however: she had a sense of ease about her, a sense of comfort in her place, which had the effect of putting others at ease. I am sure she put me at ease on countless occasions. Especially early in my time with the Sangis, when I could understand almost no Sindhi, there were many times when conversations would flow around me, leaving me feeling muddled and misplaced. I can’t remember any of the gentle and amusing things that Mehak would tell me in these moments, but how well I can remember the childlike smile that would accompany them, that innocent grin which could instantly lift a sagging mood.  Baby Mehaki Baby Mehaki Mehak was the baby of the brood, the last but most loved of our generation of Sangi children. (I myself, though last to arrive in the Sangi family, am the eldest of the ‘kids,’ being a couple years older than the otherwise-eldest, Marvi). With her especially round cheeks and bright eyes, Mehak fulfilled the role of the baby sister to perfection. Though the Sangi household was already a sunny one, Mehak herself soon came to embody that sunniness. As the other siblings grew older and started to have inclinations away from the home, Mehak seemed to grow deeper into the heart of the home itself. She knew all the ins and outs of the household. She was the one who would make certain that Papa and Ammi took their medicine whenever they were ill. She would pack Papa’s suitcase for any trip he might take, knowing better than he what all he would require away from the house. She anticipated the needs of others and responded with subtle grace. In that special way that youngest siblings sometimes have, she was able to combine her bright youthfulness with unexpected emotional maturity.  Mehak with niece Areej Mehak with niece Areej Though she was the baby of our generation, Mehak was the most excited of all to welcome the babies of the next. I can well remember her immense excitement upon the birth of Marvi’s first daughter, Areej. Mehak had designed a large poster offering in glittering letters: “Welcome Areej Fatima, our precious angel.” Mehak took to Areej, and then to the two nieces who followed soon after, with no less love than if she were their mother. And their love for her was scarcely less intense than for their own mothers. Mehaki’s new name in the home became “Kaka Mehka,” which was Areej’s early version of “Kaala (Aunty) Mehak.” Her presence was a natural balm to young children, and a source of true joy and comfort. Although Mehak was as much of a household angel as could have been desired in olden times, she was also a modern woman of emancipated intellect. She took her medical studies extremely seriously. When her other household duties had been attended to, Mehak was always to be found with a textbook on her lap. I am a bit amazed when I think back: this peaceful person was actually never at rest. She was working, she was caring for others, or she was studying. In all of these, she was giving herself wholly and sincerely.  at her bridal shower at her bridal shower Mehak was tremendously beautiful, and yet not the least vain. Her beauty was of the freshest and most natural kind. Many times I have seen her in the first moments of her day, upon rising from sleep, already in a state of rosy loveliness that most women can’t achieve even after hours at the mirror. And when she was in fact made up and adorned in wedding finery, she was absolutely radiant, as countless photos will attest. And yet she never sought compliments or attention based on her appearance. The photos of which she was most proud are those from her medical school graduation, in which she is enveloped in elaborate academic robes, her face framed by hijab, her warm eyes beaming with soft intelligence. It was her hard work and accomplishment, not her surface, in which she placed value. Closely linked to her hard work was her generosity. I happened to be living in the Sangi home at the same time as Mehak began her ‘house job,’ which I understand to be something like joining the medical rotation staff: a first stage in a doctor’s career. With her very first paycheck, she went out and bought gifts for the whole family, including me. How many of us, upon receiving a paycheck for the first time, would even think to spend it on others? And yet I am sure that this was Mehak’s natural and unquestioned instinct.  receiving Papa's blessing receiving Papa's blessing When a person like this suffers, she tends to draw the suffering inward. Not wishing to make a show of herself, or to cause unpleasantness for others, Mehak would tend to hide any pain, emotional or physical, within herself. She was subject to migraines, one of those most invisible of illnesses, which causes the sufferer such internal agony. She never revealed that pain upon her placid face, but bore it bravely, fading into the background to take rest only when it was absolutely needed. When life events brought her emotional upheaval, very few of her loved ones could know how much she must be suffering inside. It is possible that when she became ill a few months ago, this internal suffering could have aggravated the problem with her heart—but of course there is no way to know what happened with any certainty. What I feel sure of is that Mehak had a deep interior life, rich with emotions of many kinds. Although the keeping-in of pain may have caused her harm, other aspects of her interior life gave her great strength. She was deeply religious, a true believer in Islam, and one of the finest examples of a Muslim that I have known. She prayed regularly, but never made a show of it. She did not lecture others on how to act; instead, she simply acted well herself. She was a model of selflessness, generosity, and kindness.  Mehak with her husband, Ghulam Mujtaba Sangi Mehak with her husband, Ghulam Mujtaba Sangi I last saw my sister Mehak during her wedding celebrations in December 2019. A few nights before the wedding, we held a bridal shower for her in ‘my’ room (which is a great big room at the top of the Sangi house), for which I took photos. The next night we decorated the lawn and ourselves with flowers for her Wanwah celebration, and Mehak was bright and glowing among the marigolds. Our sister Moomal did the makeup for this night and the next, and she told me how special this was for her, because as a little girl Mehak had often requested: “moon khey kunwaar kayo!” (“Make me a bride.”) On the night after the Wanwah, we celebrated the Mehandi (‘henna’), at which the engaged couple receives blessings from the family and then is entertained by dancing from the siblings and cousins. The ceremony opens with all the sisters and female cousins processing in carrying cakes of henna bearing candles. Being the eldest of all, I was given a place at the front and center of the procession, which was an honor I will always cherish. I also led the dandia (stick) dance, which was the last of the evening—and though our performance was not exactly stellar, it is a sweet memory too. It was a delight to see our beautiful Mehaki sitting next to the young gentleman who would be her loving husband, though we now know how brief a time they would be allowed together in this life. After the Mehandi ceremony I had to spend much of the night packing my suitcases, because I had been called back suddenly to the US: my father’s long illness had become suddenly critical, and I was needed to help care for him in his last weeks. As a result I had to miss the actual Nikkah (wedding) ceremony, much to my great regret. Mehak was completely understanding about my need to go home to my father, and we parted with hugs and assurances that there would be many more occasions to celebrate in the future. And I returned to Sindh with the intention of seeing my Sangi family in the middle of March, at that time not knowing how widespread the COVID pandemic would become. That trip was cut extremely short: I spent a few days with friends in Karachi and then left again directly from there, as countries were beginning to close their borders in quarantines. Thus I was not able to see my sister then, and now, not ever again.

At time of posting, it has been seven days since Mehak left us. Our sister Marvi sent me a photo of her grave, strewn with fragrant rose petals. Yet it is impossible for me to grasp that she could be within it. Marvi wrote to me, “she is invisible, but she is all around us.” Mehak is not gone: she is the fragrance of the rose petals. She is the peace that will eventually bless the home once more. In this world we will forever miss her company, yet we will never be without her spirit.

48 Comments

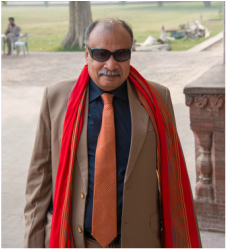

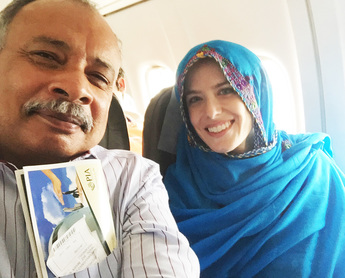

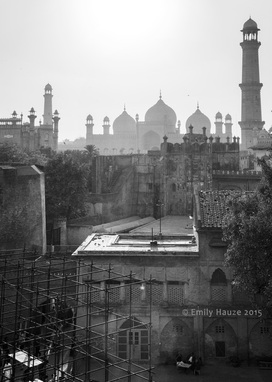

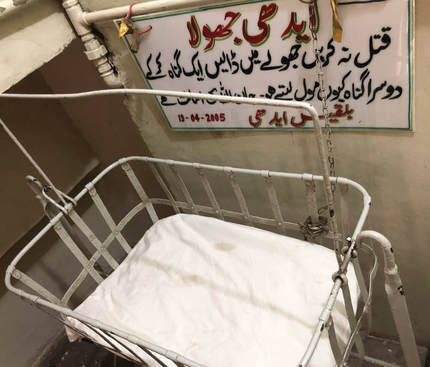

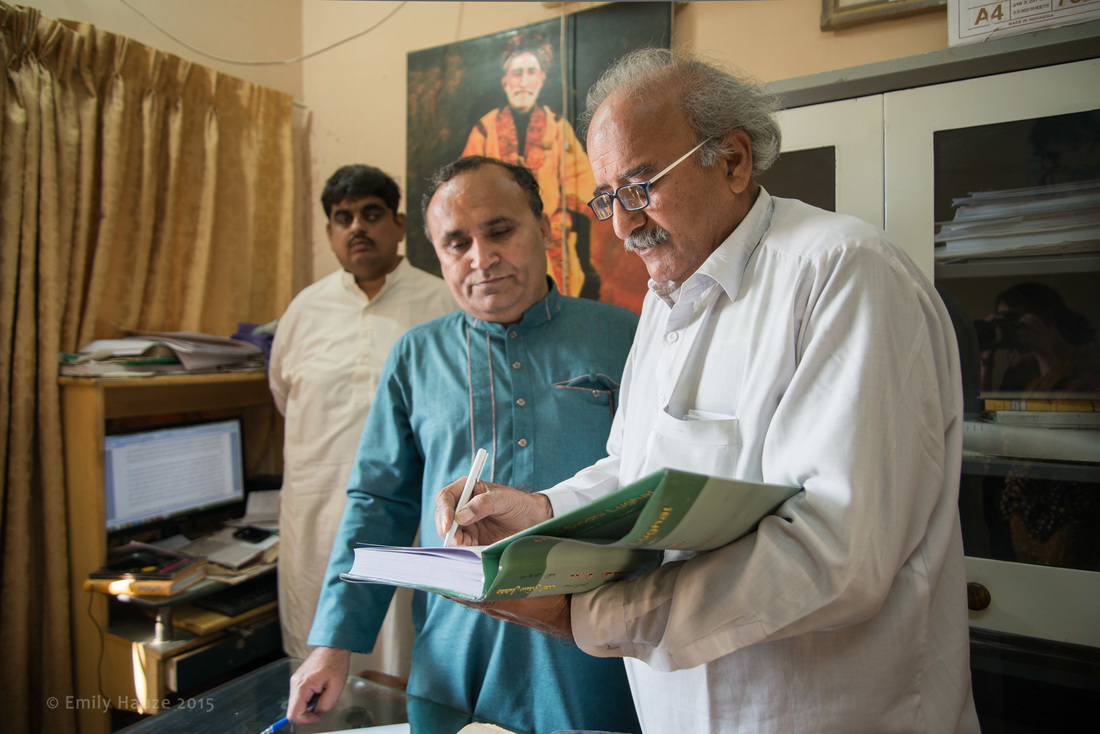

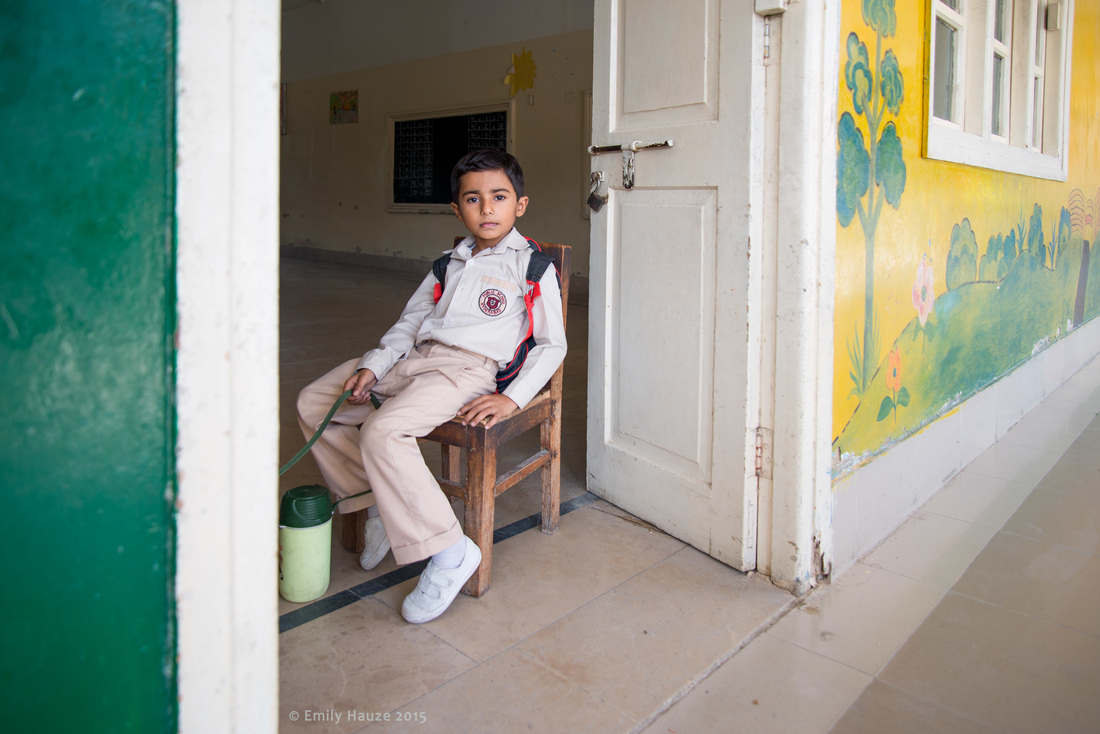

Little Sharif and the Birth of an IdeaMy heart does not require any special reason to go to Sindh. But sometimes there are particular reasons, usually weddings or births within my Sangi family, which determine the timing or destinations of my travels. When I set off for Sindh this February (2018), I had a different reason in mind. I wanted to meet Bilquis Edhi. Her name is not known to many Westerners, but every Pakistani will recognize it, at least the surname, and acknowledge it with respect. She and her husband, the late Abdul Sattar Edhi, whose recent death was cause for national mourning, established the largest charitable foundation in the country. Mr. Edhi is the name associated with most aspects of the Edhi foundation – its network of ambulances and hospitals, for example. He was the greater celebrity of the couple. But Mrs. Edhi has been known as long to me as Mr. Edhi has, for a very specific reason: Mrs. Edhi is in charge of adoptions. In fact, I have known about Mrs. Edhi since even before my whole Sindhi journey began. It was seven or eight years ago when my husband and I first had the idea of adopting a child from South Asia. That in itself is proof that there has long, or perhaps always, been a seed of interest in South Asia within me, which was only waiting to be germinated. Perhaps I could trace this interest back to many different points in my past.But the way our adoption idea came about is a simple story. I was working as a production assistant for a Philadelphia arts television show, and I had gone with my producer and her small crew to film a segment at an inner-city elementary school. There were many beautiful children there, of diverse races, but there was one boy in the second grade who instantly stole my heart. He had a round face and big, joyful almond-shaped eyes, and he was full of energy and activity. I talked to him for a few minutes during the breaks between filming. He told me his name was Sharif, and that he had recently moved to America with his family from Bangladesh. He spoke with a broad melody of enthusiasm in his young voice. I remember everything about him, down to his orange sweatshirt printed with “DUBAI” in large letters. He was, quite simply, the most adorable little person I had ever seen. When I came home from work that day, I told Andrew all about little Sharif, describing him in great detail, because he had been my favorite part of a good day. “Well,” said Andrew, “I think we’re going to have to adopt a baby from that part of the world, so that you can have one of your own!” He had been only joking, but I looked back at him with wide eyes. We were silent for a moment, and then I said. “That’s it. You have just conceived our child.” And he knew I was serious. He nodded in assent. Before this, we had spoken only a little about having children some day, and maybe adopting. But on this moment, we knew that it had been decided. We weren’t ready to start the process yet, but it became a real plan for the future. It was as simple as that. Of course, only the initial decision was simple. We knew from the outset that the process of adoption would be long and difficult. But we were not in a hurry at that point. We took our time in learning how to adopt a child from South Asia, and quickly found out that the process is extremely different for each country. India seemed the most likely option, but most of the websites indicated that prospective parents would not likely find a child under the age of four or five, and this was partly because the legal process of adopting the child could take up to two years even after the child had been located. Bangladesh and Sri Lanka seemed to have very little structure in place for adoptions in general. And then there was Pakistan. There seemed to be a different system in place in Pakistan, and we tried to understand it. We followed the online trail of clues like detectives to discover whether this might be a possible option for us. We found that many American couples have adopted babies from Pakistan – but it seemed that these couples were all at least partly of Pakistani origin, and apparently all Muslim. Would it be a problem for us to adopt, being Christians? The available information was hazy on this, given that almost all the people wishing to adopt from Pakistan were Muslim anyway. But I found enough indications that individual Christians have succeeded in adopting from Pakistan that I didn’t give up the idea straight away. All searches concerning adopting from Pakistan led in one direction: to the Edhi Foundation. That is how I learned the name of Bilquis Edhi long before my Pakistani journeys began. I marveled that this one woman had overseen all the adoptions, who knows how many hundreds or thousands, since the venerable foundation had opened. There was something about this which brought an immediacy to the whole idea, replacing the idea of paperwork and bureaucracy with a maternal warmth and familiarity. Could Mrs. Edhi perhaps help me, too? But there was a different reason, all those years ago, which seemed an insurmountable obstacle. By all accounts it was essential to have contacts in Pakistan—friends or family who can assist, make calls, submit legal papers—in order to attempt an adoption at all. And there we were, a white American couple who had perhaps never even met any Pakistanis before; how could we possibly make connections with them that would be strong enough to entrust them with such a personal and burdensome responsibility as might be needed during an adoption? Seeing no possible solution to this, we simply filed the idea away in the recesses of our memory until we would be truly ready to become parents. Somehow I always trusted, as I still do, that when we are meant to become parents, it will happen in the right way. In Karachi, 2018 Me with one of my favorite Sindhi kids, my niece Areej. Me with one of my favorite Sindhi kids, my niece Areej. The above story unfolded eight years ago. If you, dear reader, are familiar with my story, you will know that an astonishing number of miracles and adventures have occurred since then. I have been blessed with countless Pakistani friends, many of whom I could trust with very personal matters if needed. Most miraculously of all, I myself have been adopted, by a wonderful Sindhi family. (If that story is not familiar, please read earlier entries of my blog to find out how it happened.) All of these events occurred entirely independently of our prior wish to adopt a child, and perhaps they have even delayed our urge to become parents, because there has been so much new life to live in these years. But all the while the idea had been simmering within us somewhere, waiting for its time. Over the past year and a half, we began the process officially and whole-heartedly. First we had to document every aspect of our lives and get it all meticulously examined and attested by the right authorities, in order to get authorization from the US government to adopt a foreign child. That stage of the process was painstaking, slow, and expensive, but has been completed. The next stage would transfer all the field of action from the US to Pakistan. And most of the action to follow would be simply waiting. But that time of waiting could not begin until I had done one important thing: to visit the Edhi Foundation offices. My immediate family in Sindh are the Sangis of Larkana, which is a good six or seven hours drive away from Karachi, where the Edhi Foundation is based. But fortunately there are close branches of the family in Karachi as well: various uncles and cousins who often host me for a few days at a time when I come into or out of the country. My brother Faisal, in fact, has lived in the home of one of these Karachi families for the past several years, as he begins his career. It was to that house, home of Uncle Nusrat and Aunt Yasmeen, as well as almost a dozen other cousins, nieces and nephews, and elder relatives, that I arrived at the beginning of my most recent stay in Sindh. And these kind-hearted Sangis, who always treat me as one of their own, arranged for me to visit Mrs. Edhi’s office. When we made calls to the Edhi office, we couldn’t speak directly to Mrs. Edhi, but that was not surprising. Her assistant, Asma, handles most of the communications with prospective parents. And I received no specific promise that I would be able to meet Mrs. Edhi herself, but it was hinted that she is normally present at the office in the mornings, and so it might be possible to see her. My cousin Asad was the one who accompanied me that morning to the office. He is a lawyer and works from an office that adjoins the house, so he promised me that it would not be a big difficulty for him to take an hour or two first thing in the morning to take me to Edhi. We left home before 9:00, which actually is not so early, but it certainly feels early in Sindh, where most things seem not to get cranking until 10 or 11. In any case, the streets were blessedly quiet that day, and we seemed to glide effortlessly from our neighborhood into the older and more central quarter where the office lay. Some of the old buildings in the vicinity of the Edhi office.  One of the entrances to the Edhi office. One of the entrances to the Edhi office. Karachi is an enormous city, but my family happens to live only a couple miles away from the Edhi office. The distance is great enough for a significant shift in architecture, though, into a series of streets dense with what would once have been glorious and ornate buildings. The past century has ravaged Karachi, as it has done with so many of Sindh’s faded glories. Now buildings stand in disrepair, their facades obscured by tangles of electrical wire, their surfaces cracked and worn, some of their doors and windows stripped of their fine materials by salvagers over the decades. But those buildings are still wrapped in a certain elegance, and seem to breathe with stories of the past that could be told. But these streets and alleyways are still full of life – no corner of Karachi is deserted. And in one of these corners there is an office marked with red letters: EDHI. The adoption section has its office up some stairs in a very plain building, nearly invisible in its side alley. Overlooking that alley, however, are the large grey eyes of Mr. Edhi, as seen in a huge black-and-white painted mural on a jutting wall. Partway up the inner stairway toward the office there is one of the famous cradles where unwanted babies can be left safely. Its sign in Urdu reads, “EDHI CRADLE: Do not kill; leave the baby in the cradle. Why should one sin lead to committing another? Life is entrusted to Allah. Bilquis Edhi.”  A selfie in the Edhi office; the only pic I have of myself from that day. A selfie in the Edhi office; the only pic I have of myself from that day. Inside the office there is nearly nothing: just a bench for waiting and a simple desk with nothing more on it than a telephone. In front of the desk were a couple of chairs for visitors, and behind the desk was Asma. I found myself very thankful to have Asad there with me. Asma does speak some English, and I speak some Urdu (haltingly), but much time was saved by Asad’s ability to translate and explain some of the more unusual aspects of my story, and, crucially, to attest to my being a member of the Sangi family. Asma is a quietly strong, no-nonsense type of personality, and she wasted no time getting the essential information from us, and showing me exactly what documents needed to be provided still before I could be officially placed on a waiting list for a baby. I hoped that I was communicating my earnest sincerity in these quick moments, but from her minimal reactions there was no way to be entirely sure. Soon I had a list in front of me of several official things – tax returns, bank statements, photos of our house – that I should submit to the office along with their official form. But as Asma and Asad’s eyebrows began to raise in that universal, “okay, will that be all?” expression, I summoned the energy to ask what I had been hoping. “Would it be possible to meet Mrs Edhi, just to say hello?” “Meet her? Okay,” Asma replied, giving the single tilt of the head to the right, which generally signals assent in this part of the world. I had thought she might summon Mrs. Edhi from some back office to come and meet us there in the anteroom, but instead she handed me my photo album and signaled for me to come with her to the next room, right on the other side of the wall, through an already open door. It was clear from her body language that Asad was not to come along, so I knew I would be on my own, with my timid Urdu. But there was no alternative, so I quickly followed on my own.

There in that room there was almost nothing at all. It was about the size of a bedroom, with bare, blue-painted walls and windows on two sides which let in a gentle, slatted light. There may have been a small bookcase or the like in the room, but nothing that made it resemble an office, and in fact, nothing that made it resemble any particular type of room. There was nothing there except for what was essential: Mrs. Edhi herself, reclining on a charpai. “She is sick,” Asma said clearly and in English. “So please: only five minutes.” She placed a chair next to Mrs. Edhi’s cot and gestured for me to sit, and then left the room. “Assalaam-o-alaikum,” I said, as calmly as I could. “Wonderful to meet you.” I knew I was in the presence of a great woman, someone I have admired for years, someone who will be remembered lovingly by history. I wished I had some way to convey that respect to her; I can only hope that it came across a little in my behavior. Mrs. Edhi looked very much like I imagined she would, knowing about the very simple way in which the Edhis have chosen to live. She looked just like any grandmother in my own Sangi family. She has rounded features and smooth skin, with thin hair of a light brownish hue which was pulled neatly away from her face. She wore a simple cotton shalwar qameez of a light, neutral color, and she lay with another light sheet lightly bunched at her sides for comfort, and some sort of pillow very slightly propping up her head and shoulders. Although her body remained inactive, her mind was clearly alert. Normally I might worry that a person of any age, let alone an elderly or ailing person, would probably not remember me after one quick meeting. But Mrs. Edhi is the kind of person who will remember. She has been placing babies with families for decades; she oversees every single adoption in the Edhi Foundation. By some innate instinct she knows which babies should go to which parents. She can see qualities in people beyond what most can see on the surface. This is a bit intimidating, but also reassuring. I knew that as long as I presented myself as I really am, I could trust her to understand. After my quick greeting, I did my best to speak a little Urdu. “Mera showhar aur main adopt chahte hain.” (My husband and I want to adopt.) “Showhar ka naam kya hai?” she asked. My brain had to work quickly to pick out these words, which were not slowed down at all for a struggling Urdu speaker. “Iska naam Andrew hai,” I said, and took the opportunity to show her my album, since I had written out our names in large letters on the front. “Andrew Hauze, aur main Emily Hauze.” She nodded and motioned for me to show her what was in the album. She looked carefully at each picture, asking me to tell her who the all people were. Vo Andrew hai, mera showhar…. vo mera Sindhi baap hai, aur Sindhi ammi…. vo donon nieces hain, I managed to say. (That’s Andrew, my husband … this one is my Sindhi father, and Sindhi mother… those are both nieces, etc.) She nodded and seemed to understand the relation I have with my Sindhi family, though I didn’t have the time or linguistic means to explain it to her. “Ham eissaa’i hain,” I added (‘we are Christians’), feeling it was important that she have that in mind, too. She nodded without looking up from album, and said “koi baat nahin,” or something like that, meaning ‘that’s no problem.’ That little gesture from her was actually the most reassuring thing that I experienced during the meeting. I knew that she readily works with Christian couples who want to adopt and that she would have no objection to us on these grounds, but had been expecting to hear much more about how difficult it is to find Christian babies, and how we might have to wait a very long time. Indeed, we may have to wait a long time, but what mattered to me was that she did not discourage us from trying. She did not treat me any differently, I think, from any other prospective mother. When she had seen all the pictures, I sat back in my chair and looked at her, trying (unsuccessfully) to discern any impression I might have made. “Showhar ka kaam kya hai?” she asked. (What is your husband’s work?) “Professor hai,” I answered. “Music professor, university main.” She seemed pleased by this answer. I hoped to keep talking, but this was the moment when Asma returned, as usual polite but stern. “Madam,” she said to me, needing no other words to indicate that my time was up. I didn’t want to overstay my welcome, and quickly rose, saying “it was so nice to meet you.” Not wanting to miss my chance, though very concerned not to appear rude, I asked Asma if I could possibly have my picture taken with Mrs. Edhi. At least, she did not appear surprised or offended by the question. She simply asked Mrs. Edhi if a pic would be okay, and when Mrs. Edhi shook her head, saying something like “it’s not a good time, since I’m unwell,” I dropped the idea, praying inwardly that there will be another chance in the future. Thanking her again, I let myself be ushered back out of the room. That was the end of my first visit to the Edhi foundation. I returned a couple days later, having gathered all the additional documents needed. Andrew had quickly put together all these things, scanned them, and sent them to me for printing. When I returned, I brought Asad again, as well as my Chachi (aunt) Yasmeen, who is also Asad’s sister. I want to mention Yasmeen here before closing this blog entry, because to her is owed a deep gratitude of my heart. She has agreed to take on the responsibility of actually picking up the baby at whatever time we become lucky enough to receive one. The Edhi Foundation prefers to deliver babies to their new families almost immediately upon receiving them, and this means literally within a few hours of receiving them. This is of course a tremendously weighty thing to ask anyone to do, even though I hope to be able to come in person as quickly as possible myself. If it weren’t for my Chachi’s kindness (as well as my deep trust in her), I would not be able to to hope for this adoption at all. Sitting around Asma’s desk on that second visit, Asma made sure that she had all the local contact numbers for my Sangi family and knew exactly who to call at such time as a baby should arrive. The waiting time may yet be very long, especially since I have specified a preference for a boy. But at least that waiting time has truly begun. Before I left, Asma shook my hand, and her face took on a beautiful, broad smile, for the first time that I had seen. Back at home, I gave Chachi Yasmeen a hug and thanked her again for her help in this. She too smiled, and said with tender excitement, “we are also waiting for your baby.” And so: we are waiting. Prologue - Surprises Passing through security in the Karachi airport is different for a woman than it is for a man. This is true, I believe, in most airports in the Muslim world, but my first experience of it was in Karachi. Men place their bags on the nearest conveyer belt and continue through a typical open-frame metal detector. I think I attempted to heave my carry-on bag onto that belt at first, since there were very few people there and I had no reason to think this was a men-only line, but I was soon directed to a separate and less obvious line for ladies. The luggage conveyor belt looked the same as the other, but the metal detector leads directly toward a curtained cubicle, where all women must be privately inspected. A female security officer held open the curtain and beckoned to me as I passed through the metal detector. She was wearing a smart uniform that includes a dupatta over her hair, beneath the hat and tucked in place at the shoulders. I obeyed, and she swiftly closed the curtain behind me. In that moment I couldn’t help but think of the purdah, with all its complex associations. The women’s security check could perhaps be called a miniature purdah. Inside that room, the woman used her wand device to check under my arms and around the edges of my clothes. Given the often loosely flowing garments worn in this part of the world, it is easy to see why this sort of check is prudent. But her attitude was gentler than what I’m used to from Western security checkers, who are trained on high alert and treat each passenger as a likely threat, whether they be men or women. But this woman treated me with a sort of collegiality, like a fellow woman, almost as if she were performing a service rather than forcing an inspection. She asked where I was flying, and smilingly sent me on my way. The whole thing took only a few seconds, and as I left I was surprised to think how pleasant it actually was. My first instinct had been to think it was a bit silly or maybe even degrading to be sent to a separate line and treated differently from male travelers, especially since it necessitates a longer procedure. But the effect was not a feeling of being belittled or made to feel second-class. As she lifted the curtain for me to leave the little room, I felt that I had actually been given a strange privilege. And along with that was a feeling of surprise which has accompanied so many of my discoveries about women’s lives in Sindh, which have so often defied my expectations. It has been in my mind since the beginning of this blog project to write an entry about women in Sindh. Questions about women’s lives, opportunities, hardships and advantages, have been asked me more than perhaps any other topic, and I have probably spent more time pondering these issues than any others. So why have I so long avoided the actual writing of it? I will admit to a certain degree of cowardice. The subject is simply so vast, so nuanced, and so sensitive. I think most people will agree with me that there is no simple answer to the question, “what are women’s lives like in Sindh?” Nor yet is there a clear answer to the question, “where are women better off: in America, or in Sindh?” I cringe at having to give a glib answer to these questions, and so I often avoid it--but the reason is not a lack of thought on the topic. The reason for my hesitance is that I care so much about the question, and it is so weighty, that I have never wanted to treat it superficially. I will not be able to avoid speaking in some broad generalizations, but I will try to temper them with careful consideration. For the world is full of exceptions, and there are unexpected realities in all the different levels of society. In fact, the expectations placed upon women, especially daughters, have given me some of the greatest challenges during my time in Sindh. It has been a challenge not only to attempt to conform to these expectations, but often a challenge even to learn what they are. And what can be more embarrassing than to discover after the fact that you have behaved inappropriately, simply because you didn’t know what was expected? Sindhi people are forgiving of these errors, fortunately, and I think I have caused no major catastrophes. People often pose the question to me of which country is better for women, Pakistan or the USA, as if this would be easy for me to answer in a few words. But I cannot make that call without deep pondering, and perhaps cannot make it at all. What is “better” perhaps comes down to the individual woman and her temperament. But there are two broad statements which I can make with confidence, and perhaps those will help me to build some more specific arguments. The first statement is that, as a woman, I unquestionably have more freedom of movement and of choice in the USA. For those who value freedom above all else, the USA is clearly the better place for a woman to live. I will speak more of what I mean by “freedom” in the paragraphs to come. But I must say first that, at least in my view, freedom is not the only blessing a woman may enjoy. And there are certain honors, luxuries, and beautiful relationships that can grow in a society like that of Sindh, and which do not thrive in America. And my second broad statement is that, to my mind, the societal construct concerning women and the segregation of women from men is the most powerful social force at work in Pakistan, for good and ill. I. My own early life, for comparison |

| *I think it’s important to note that this lack of poetry and lack of rhyme is specific to my white-Protestant upbringing, and I would have had a very different perspective had I grown up instead with the hip-hop and rap poetry of Black America. That is a culture in which poetry is as alive and vibrant as anywhere I can imagine, and in which the idea of rhyme has reached new heights of virtuosity. But that is not the culture in which I grew up. |

Hearing Sindhi poetry recited reminded me much of the life of a poem is in its music: in the way in which it sounds and dances in the mind, whether that be in a traditional rhyming meter or an unrestricted free form. If that music were not essential, then the Meaning could be just as well expressed in prose, in paragraphs. Thus the “Essence”, which is what all translators really want to capture, is not in the “Meaning” alone. It is also not to be captured in the form alone, nor in the style. That intangible Essence refuses to be even described, let alone defined. It is like trying to bottle the scent of a rose directly from the air. It is entirely impossible.

And yet, there are few reactions more frustrating to receive on a translation than that old chestnut: “Somehow it just doesn’t capture the essence of the original.” There is no way to argue against this criticism, because it is invariably correct. The Essence is not available for bottling and re-selling. And so, how to respond to that critique, other than to say: “I tried my best -- and I will keep trying” -- ? My best hope can never be to convey the true Essence, but simply to limit the pain of its loss.

And having recognized an inevitable loss, how should the translator behave? In academic circles it has become trendy to debate whether translation is really an “act of brutality” against an original text. Although the word “brutality” seems a bit extravagant, the idea is really not far removed from comments received about a translation “not capturing the essence.” According to this thinking, the translator is doing something unnatural and unkind, mutilating a work of genius by sending it through a linguistic shredder and offering the results as if they were still whole. And that is an engaging idea -- until one remembers that the translator has actually done nothing at all to the original poem. It has not gone through any shredder: the original poem still exists. There was no attack and no dismantling, and more importantly, no replacing. The translation wishes to emulate, but not to dethrone, the original.

It seems to me that the best way to think of a translation is as a bridge. The original poem has its place, its home, in its language. All those who know the language have access to the poem, but it is out of reach for all others -- until someone builds a bridge. That bridge must start from the native language of the translator, who undertakes the task to connect the new reader to the original. The better the translation, the more solid the bridge, and the more likely it is to transport new readers back to the source. A poor translation requires much from the reader, much clinging and perseverance, if he wishes to understand the poem, and many will be lost along the way. A fine translation, by contrast, will allow the new readers to pass smoothly as if traveling in their own country, and yet experience something they couldn’t otherwise see. The strongest bridge of all is that which inspires the new reader to try to learn the language itself, so that he can approach the poem in its genuine Essence.

And so, that is my project, however long it takes me -- years certainly, or a lifetime, perhaps. I hope I can build a sturdy bridge for future travelers. All pilgrims are welcome on the road toward Bhit Shah.

And yet, there are few reactions more frustrating to receive on a translation than that old chestnut: “Somehow it just doesn’t capture the essence of the original.” There is no way to argue against this criticism, because it is invariably correct. The Essence is not available for bottling and re-selling. And so, how to respond to that critique, other than to say: “I tried my best -- and I will keep trying” -- ? My best hope can never be to convey the true Essence, but simply to limit the pain of its loss.

And having recognized an inevitable loss, how should the translator behave? In academic circles it has become trendy to debate whether translation is really an “act of brutality” against an original text. Although the word “brutality” seems a bit extravagant, the idea is really not far removed from comments received about a translation “not capturing the essence.” According to this thinking, the translator is doing something unnatural and unkind, mutilating a work of genius by sending it through a linguistic shredder and offering the results as if they were still whole. And that is an engaging idea -- until one remembers that the translator has actually done nothing at all to the original poem. It has not gone through any shredder: the original poem still exists. There was no attack and no dismantling, and more importantly, no replacing. The translation wishes to emulate, but not to dethrone, the original.

It seems to me that the best way to think of a translation is as a bridge. The original poem has its place, its home, in its language. All those who know the language have access to the poem, but it is out of reach for all others -- until someone builds a bridge. That bridge must start from the native language of the translator, who undertakes the task to connect the new reader to the original. The better the translation, the more solid the bridge, and the more likely it is to transport new readers back to the source. A poor translation requires much from the reader, much clinging and perseverance, if he wishes to understand the poem, and many will be lost along the way. A fine translation, by contrast, will allow the new readers to pass smoothly as if traveling in their own country, and yet experience something they couldn’t otherwise see. The strongest bridge of all is that which inspires the new reader to try to learn the language itself, so that he can approach the poem in its genuine Essence.

And so, that is my project, however long it takes me -- years certainly, or a lifetime, perhaps. I hope I can build a sturdy bridge for future travelers. All pilgrims are welcome on the road toward Bhit Shah.

a post-script: I intend to append here a specific discussion of one of the brief translations I have already done of a verse from the Shah jo Risalo, with explanations of my specific thinking in making the choices I have made. That should give a little more tangibility to the theoretical ideas I have discussed above. For now, here is a link to a Facebook album in which I have compiled those few verses which represent the beginning of my attempt: "Translations from Shah Latif"

I have been three times to visit the fishing community on the Indus banks near Larkana, so I will tell this story in three parts.

Part 1. The ancient Indus, yet a new world for me.

For the first part of the story I must think back more than a year ago and pull the details out of the already dusty recesses of my memory. It was at the very beginning of January in 2015, during my first trip to Sindh. The landscape of my adoptive home, which is so rich in color and variety, especially around Larkana, was still fresh and new in my eyes. The Sindhi landscape still warms my heart and will always delight my soul, but there is a tug of nostalgia in me for that brief time when it was still completely new. And all was a surprise. What a precious feeling that is -- the complete newness of love. And though I will never be able to discover Sindh completely anew like that again, I hope I will always be able to remember that feeling.

On that particular afternoon, I had already been dazzled by several new sights about and around Larkana, and I was feeling ready to head back home. But Papa Saeed had one more location in mind, just before sunset. We were riding in his Jeep, which is the vehicle Papa loves best, because it frees him of the shackles of having to drive on the real, paved roads of town (which roads, it must be said, are paved very poorly in many cases anyway). Our drive on that afternoon took us first onto a very sandy passage that still nonetheless resembled a road, but then soon down a steep hill that seemed not much more solid than a sand dune. Once down that stretch, the Jeep proceeded to bump and jostle its way across a rocky terrain that eventually opened up on the vast expanse of the Indus river bank.

On that particular afternoon, I had already been dazzled by several new sights about and around Larkana, and I was feeling ready to head back home. But Papa Saeed had one more location in mind, just before sunset. We were riding in his Jeep, which is the vehicle Papa loves best, because it frees him of the shackles of having to drive on the real, paved roads of town (which roads, it must be said, are paved very poorly in many cases anyway). Our drive on that afternoon took us first onto a very sandy passage that still nonetheless resembled a road, but then soon down a steep hill that seemed not much more solid than a sand dune. Once down that stretch, the Jeep proceeded to bump and jostle its way across a rocky terrain that eventually opened up on the vast expanse of the Indus river bank.

The nomadic settlement.

The nomadic settlement. And what a view it is from there: the river Indus stretching wide but placid, its waters almost still, such that you might not even notice which direction the river was flowing. And alongside that peaceful giant of a river stretched a wide beach, not of sand, but of gentle silty dust, which at water’s edge becomes a grey slippery mud.

Farther back from the river, where the terrain changes into a more typical mix of rocks and low plants, there arises a chain of huts, all ramshackle and bending low under the pressure of sunlight and the harshness of reality. These are the homes of the nomadic fishing community, who live in this majestic natural setting but in conditions of abject poverty. I cannot hazard a guess as to whether the beauty of the river and sky can possibly console these fisherfolk amid the starkness of their deprivation.

The people who live here captured my interest at once, and we (Papa and I) seemed to be just as interesting to them. The menfolk usually linger in the background, rarely approaching, but the women (generally older ones) come forth readily to offer their greetings, and the children burst towards us in great curiosity and enthusiasm. The women are always kind, but they seemed a bit wary of us at first. Although the Sangi home is only a few miles from this settlement, it would appear that even Papa is an alien from another planet descending upon them, so different is their way of life. But Papa greets them as equals, addressing each woman as “adi” (respected sister). And if they seem surprised to be given such respect, he insists to them that “we are all Sindhis, aren’t we!”

The beautiful faces that greeted us that day.

The beautiful faces that greeted us that day. A bit of wariness is of course understandable, from people of such poverty, when they see a well-dressed doctor and his strangely white daughter and her armed guard, all barreling fearlessly over their terrain in a Jeep, even if it is our old and somewhat rusted one. I’m sure I would be quite wary if I were in their position. But that emotion never lasts long in them -- Sindhi hospitality and warmth is strong in their hearts, and they quickly warm to us, especially once they see that we are just visitors and curious ourselves. And the children, in any case, are never wary. They rush to surround us with their bright faces, and delight in showing us their nets and fishes and anything else they might have on hand.

My attention was drawn to the still waters of the river, and especially to a few strange and still displays moored in them. There were a pair of wooden Indus boats, which are always a poetic image, especially when they float there, empty and waiting. But more surreal was the line of strange birds, all perched on a slender and uneven branch, which was raised by similar but vertical pegs to hover a foot or so above the water. The birds sit there in great solemnity, uttering no sound, and rarely moving at all. At first I had thought that they had simply paused there for a rest in the midst of their regular soarings, but looking more closely I realized that they were tied to the spot. I was even more unsettled to learn that they had been blinded, though I could not understand the reason that was explained to me at the time. I later learned that they are held there for the purpose of luring other birds to the spot to be caught. And thus, as sometimes happens, a scene that appears magical upon first glance turns rather darker upon inspection.

Baji is at the center, grinning directly at the camera.

Baji is at the center, grinning directly at the camera. But I could hardly brood on that notion when surrounded by such bright children, who circled around us with increasing excitement.

One particular girl, probably eight or nine years old, caught my attention somehow. Though she had no dazzling beauty, she stood out from the crowd because of her honest, open demeanor, a special friendliness, and, it seemed to me, a noticeable intelligence in her eyes. She was especially plainly dressed. All the children wear the clothes of the poor, of course, but some of the girls nonetheless glow with bright colors and their own natural glamour. But this girl made no effort at glamour; she wore her dupatta tightly around her forehead in the manner of a kerchief. But I haven’t fully described her what drew me to her. Perhaps you, dear reader, will recognize the feeling of being in the presence of someone who seems especially real to you. Something about a personality that stands out against others. It wasn’t the feeling of having known her for a long time -- I didn’t feel like I knew her at all. But I felt nonetheless like she was someone worth knowing, someone worth getting to know.

I asked her name -- that was one of the few full sentences of Sindhi that I could already muster at that time -- “tunhjo naalo chhaa aahey?” But I was surprised, and thought perhaps that I had misspoken, when she responded simply: “Baji.” Baji is a word commonly used for “sister” (usually, an elder or respected sister) -- could this really be her name? “Tunhnjo naalo Baji aa?” I repeated somewhat haltingly. She nodded with her simple smile, and the other children confirmed that, yes, this was Baji. And I was satisfied that at least this was the name she goes by -- though surely she must have some other proper name as well. But to this day I only know her as Baji.

Pics taken just before we left on that day. Baji is near me in all of them (wearing the striped dupatta). You can see her vibrant expressions, as well as those of the other children, who surrounded me with such genuine and infectious joy.

I don’t remember much more from that first visit to the Indus fisherfolk. The rest has blurred into a general impression of the calm river, the laughing children, the sky and the soft sand. And I gave a special farewell to Baji before we returned to our Jeep to climb back up the dunes towards the city.

Part 2. Royal throne of fishing nets

I was dressed more like a Sindhi woman this time.

I was dressed more like a Sindhi woman this time. My second visit to the fisherfolk, in November 2015, was one of the loveliest of all my experiences in Sindh. I wrote it up for my Facebook page at the time, and since the feelings of the day will be freshest in that telling, I will copy that text here, but I am expanding it to fill in some details that I omitted at the time.

We arrived this time in early afternoon, and the sun was very bright overhead. I was eager to see the sweet children of the fishing community again -- particularly my favorite little girl, Baji. As soon as we were out of the Jeep and among the children, I scanned the group for Baji, and didn’t see her among them. We asked for her, and there was some confusion as to her whereabouts -- she was on the other side of the river, by some reports, or she was inside, or busy with something. These answers could not all be true, so we kept asking. And so the message that Baji was being summoned by these foreign visitors began to travel more quickly among the fisher folk, and eventually it had its effect: and we saw on the horizon that Baji herself was running along to join us.

Distraught Baji

Distraught Baji But Baji's face revealed an emotion quite unlike the joyful confidence that I had expected. She appeared distraught and worried. Although she didn’t seem to be crying, she was almost gasping with some sort of tumultuous emotion.

I gave her a hug, which she accepted gently, but her mood remained troubled, and this troubled me even more. I tried to find out from Papa what might be worrying little Baji. He did not seem to make much of it. “ACTUALLY SWEET EM,” he said, “SHE IS VERY EMOTIONAL TO SEE YOU AGAIN.”

“It is not the emotion that I might have hoped for,” I said, but I’m not sure Papa heard me.

There was an especially large group of excited children circling round us this time, inviting us to walk with them along the riverbank. I reached for Baji’s hand, and felt some relief that she was willing to offer it; another girl took my other hand, and the whole bright and bubbling group of us began our stroll. The children were so buoyant with energy that I hardly noticed when Baji began to sink back a bit into the crowd.

I gave her a hug, which she accepted gently, but her mood remained troubled, and this troubled me even more. I tried to find out from Papa what might be worrying little Baji. He did not seem to make much of it. “ACTUALLY SWEET EM,” he said, “SHE IS VERY EMOTIONAL TO SEE YOU AGAIN.”

“It is not the emotion that I might have hoped for,” I said, but I’m not sure Papa heard me.

There was an especially large group of excited children circling round us this time, inviting us to walk with them along the riverbank. I reached for Baji’s hand, and felt some relief that she was willing to offer it; another girl took my other hand, and the whole bright and bubbling group of us began our stroll. The children were so buoyant with energy that I hardly noticed when Baji began to sink back a bit into the crowd.

| Our path at first followed along the higher bank, where the mud had hardened into firm ground. At one point, though, Papa asked if I wanted to go down closer to a particular boat, where a couple of young boys were beckoning to us. Unable to resist, I started down the hill, towards where the ground was looser and muddier. These boats were very close to the shore, though, and there was some hay laid down on the mud that looked like it might possibly support me in my last steps toward the boat. I proceeded cautiously, but in vain: my right foot sank deep into the soft clay mud, immersing my shoe entirely. At this point I thought: I've come this far, so might as well go the remaining few steps without shoes. I left both my shoes sticking right there in the mud, and carefully trod the rest of the way toward the little boat. The grinning boys were waiting for me there, and I sat with them for a sunny moment. I was a bit worried about ruining my nice new suit (a present from Ammi Saeeda which I was wearing for the first time), but surely this was worth it. As I got back up off the boat, the children took me by the hand and helped me not to get too muddy on my return walk. One of them took my shoes for me, which I would have only further muddied by putting them on my feet. |

I walked barefoot with the children back up the hill, and I am thankful for that short walk, because it was a sensation I had never before experienced. My feet expected the familiar grainy feeling of beach sand, interspersed with tiny rocky hazards. But this was nothing like ocean sand: it was infinitely more gentle. Even that firmer terrain where the mud has mostly dried into a clay, the texture is fine and silky and a bit spongy to the step. My feet are unusually tender and uncallused, not used to any prolonged barefootedness, so I was expecting this walk to be uncomfortable if not painful for me. But it was quite the opposite: feeling the banks of Sindhu beneath my steps was purely delightful.

We were led to a place where some fishing nets were spread on the ground, which we used like a rug. There was a great beauty in those strong fishing nets, the beauty of sturdy simplicity, and I was as honored to sit on them as I would be on the finest royal carpet. There was tea prepared for us, I was told, to my great delight.

But before we drank it, the children tended to my muddy feet. And this was the truly remarkable event of the day. One or two of them brought a metal pitcher full of water, which they slowly poured over my feet until the mud had been washed away. Another child took my muddied shoes and rinsed them off in the Indus. They tended me with such love and simplicity -- I am unable to find words to describe this feeling of communion. One might assume, seeing the photos out of context, that they were serving me as one high above their station, or that I had demanded such service, but that was not the situation at all. I wouldn’t have even thought to ask for such gentle service as they provided, nor did I wish them to feel in any way inferior to me. And they did not treat me as an outsider whom they were forced to serve, but more like a respected elder sister or aunt they had always known and loved, as one of their own.

But before we drank it, the children tended to my muddy feet. And this was the truly remarkable event of the day. One or two of them brought a metal pitcher full of water, which they slowly poured over my feet until the mud had been washed away. Another child took my muddied shoes and rinsed them off in the Indus. They tended me with such love and simplicity -- I am unable to find words to describe this feeling of communion. One might assume, seeing the photos out of context, that they were serving me as one high above their station, or that I had demanded such service, but that was not the situation at all. I wouldn’t have even thought to ask for such gentle service as they provided, nor did I wish them to feel in any way inferior to me. And they did not treat me as an outsider whom they were forced to serve, but more like a respected elder sister or aunt they had always known and loved, as one of their own.

with a happier Baji.

with a happier Baji. Once my feet were clean, I was handed a cup of tea, which was as rich and delicious as always here in Sindh. I asked Baji to come sit next to me, which she did, and I was deeply relieved that she seemed to have overcome her earlier fit of distress. A small boy brought us a vat half-filled with water and various shining fish that he had caught that morning, just to show us his fine work. And the children were circled all around us, and their small forms also provided us a kind of dappled shade against the bright sunlight. And their sparkling laughter had the same kind of dappled effect upon my ears: somehow their laughter seemed more musical than most, with a bright range of tones like a fine Javanese gamelan. I asked Papa to take a quick video to capture that sound, though (as so often happens) the laughter had diminished by the time he heard me and started the camera rolling. As a result, much of the laughter you hear on the video is that of Papa himself, hoping to urge the children into a repeat performance of their previous chuckles. But you can get a sense of those sounds if you listen closely between Papa’s prompting guffaws.

This was the kind of moment that cannot last long, by its very nature.... inevitably we were soon up again and getting back into the Jeep.... but all those sensations still live in me: the velvety springiness of the riverbank, the texture of the fishing nets, the glint of the newly caught fish, the silvery laughter of the beautiful fisher children.

Part 3: A mystery unraveled

My third visit to the Indus fisher folk was the least joyful of the three, given that it lacks the surprise and newness of the first visit and the almost mystical exhilaration of the second. But it was probably the most important visit nonetheless; the visit in which I learned the most about the people, and particularly about little Baji.

This was during my most recent visit, in April 2016. The riverbank was the last of our stops on that day’s photo outing, timed to coincide roughly with sunset. There were three of us: myself, Papa Saeed, and our guard, who was new to us but served us very dutifully throughout my stay. His name is Abdul Khalique Bhutto, but we liked to call him “Bhutto Sahib.” (There is nothing odd about this, since it is his name, after all. But I should explain for Western readers who might not realize that the phrase “Bhutto Sahib” will always inevitably bring to mind the great former prime minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. And given that my guard Bhutto Sahib is also quite a young man, there is something vaguely amusing about this.) The three of us had previously been roaming around other parts of the riverside, where the Indus waters were somewhat more actively rushing than I had otherwise seen.

This was during my most recent visit, in April 2016. The riverbank was the last of our stops on that day’s photo outing, timed to coincide roughly with sunset. There were three of us: myself, Papa Saeed, and our guard, who was new to us but served us very dutifully throughout my stay. His name is Abdul Khalique Bhutto, but we liked to call him “Bhutto Sahib.” (There is nothing odd about this, since it is his name, after all. But I should explain for Western readers who might not realize that the phrase “Bhutto Sahib” will always inevitably bring to mind the great former prime minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. And given that my guard Bhutto Sahib is also quite a young man, there is something vaguely amusing about this.) The three of us had previously been roaming around other parts of the riverside, where the Indus waters were somewhat more actively rushing than I had otherwise seen.

my shady perch

my shady perch But despite all that interesting scenery, I was eager to visit with the fisher children again, and of course, especially Baji. I had not forgotten her unusual behavior the previous time, and I hoped to find that it had simply been a matter of that day; perhaps something else had been bothering her, and this time she would be her normal self again. I pondered this as we paused at a roadside establishment overlooking the fishing village. I can’t call it a cafe, as it was hardly more than a shack, and it could not even provide us the Coca-cola with which its sign had lured us. But we were comfortable for that moment sipping bright orange Fanta from enormous bottles (no small sizes were to be found) under the shade of the thatched roof. The temperature at the time was the hottest I had experienced in Larkana, about 42*C (108*F), but I tolerated it pretty well, as long as I had frequent access to shade. (I was lucky, however, that I returned to the US when I did, because just a few weeks later my Larkanian family was having to endure temperatures up to 53*C -- an astonishing 127*F -- and such will be their lot for much of the rest of the long Sindhi summer.)

In any case -- at that moment I was perched on a wooden pallet in our chosen roadside shack, enjoying the shade and the breeze above the river Indus. The long highway and massive bridge stretched quietly behind me. Traffic on that route is steady but sparse, and the vehicles you can see are as likely to be camels as trucks. Before me stretched the dusty road from which we would soon descend, in our Jeep, to the community below. From above, the nomadic settlement seemed peaceful, rather organized, almost like a proper village, despite its light and shabby materials. A gentle glowing light was falling on those drooping roofs in anticipation of sunset.

In any case -- at that moment I was perched on a wooden pallet in our chosen roadside shack, enjoying the shade and the breeze above the river Indus. The long highway and massive bridge stretched quietly behind me. Traffic on that route is steady but sparse, and the vehicles you can see are as likely to be camels as trucks. Before me stretched the dusty road from which we would soon descend, in our Jeep, to the community below. From above, the nomadic settlement seemed peaceful, rather organized, almost like a proper village, despite its light and shabby materials. A gentle glowing light was falling on those drooping roofs in anticipation of sunset.

Welcoming smiles on dear faces.

Welcoming smiles on dear faces. As soon as we three had gotten our fill of Fanta from the huge bottles, we got back into the Jeep to descend and greet our fishing friends below. By this time I had grown used to the way our vehicle tolerates the steep descent into the quasi-sand dunes, and the bumps along the rocky path to our destination, and yet I was a bit panicked by the particular route along the shoals that Papa chose on this occasion. I didn’t mind the proximity to water as much as the precarious angle that the Jeep assumed -- leaning heavily to the left, the passenger’s side, making me feel that I would be the first to tumble into the river if the vehicle lost its balance. Thankfully we remained upright until we’d reached a spot where we could park.

And by now, the fishers have learned to recognize that green Jeep from a distance. This time we were greeted warmly and without any reserve from the womenfolk, and the children once again bubbled with excitement. And I was pleased to be able to communicate a bit more with everyone -- though my Sindhi is still atrocious, I could maintain a certain level of light chatting without great trouble. And I myself was able to ask them this time, “Baji kithey aa?” (Where is Baji?)

They had perhaps been anticipating the question, and the same flutter of inquiry started buzzing between them as the previous time, as they conferred to figure out where she was. And again I tried to follow along with what they were saying, picking out only bits and pieces, though certainly more than the last time. “Baji pareshan aahey,” one of the children told me -- “Baji is upset.” My eyes widened and I asked “chho?” (why?) but the child shrugged, and then said something that I couldn’t quite understand.

Around this time, Papa’s phone rang, and it was apparently a rather important phone call, which drew him away from the crowd of people. I learned later that it was his assistant at the clinic, calling to update him on the many patients who were waiting for his evening arrival. This meant that I was on my own with my weak Sindhi to try to communicate with my fisher friends. Bhutto sahib can speak some English, but when I looked toward him I saw that he was also on his phone (though still paying attention to my surroundings, of course), and in any case he would not be able to provide the linguistic help I needed.

As I was waiting for Baji to appear, one of the kindly women was sitting with me and trying to tell me about her, but I was understanding very little. The one thing I did understand from her was, “Baji does not have a mother.” I was sorry to hear this, but somehow not surprised. Baji did somehow seem more like an orphan than the other children, in some inexplicable way. But -- could this be the reason why Baji was upset? Now, at this moment? The other things the woman said would probably have helped me understand the whole situation, if only my Sindhi were strong enough.

After a few more minutes, Baji herself did appear, at the arm of another one of the older women, leading her towards me. I could tell from a distance that she was once again in distress -- this time even more than before. I greeted her with a hug, which she didn’t refuse, but also could not really share. In this moment I wanted nothing more than to calm her, but without understanding the problem, I was helpless. I looked at her as gently and sympathetically as I could and asked, “Baaji, chho khush na aaheen? Maslo chhaa aahey?” (Baji, why are you not happy? What is the problem?)

But Baji was not able to answer, still gasping and crying strange, dry tears. I looked to her companions, young and old, and asked the same question. They were all looking on with kindly and untroubled faces. One of the older women did offer the answer, though I couldn’t understand it fully. I caught some of the words she was saying -- “she -- thinks -- take --” but I could not make sense of the whole thought. Desperate for a translation, I looked over the heads of the children to where Papa was standing, some distance away. He was quite absorbed in that phone call, however, and did not hear me trying to call for his assistance. The kindly woman repeated her explanation, but I still did not catch on.

I sat down on a sort of a bench and urged Baji to sit next to me, and I tried to treat her in the most friendly and least frightening way I know how. But I was utterly baffled. This bold, bright girl who had captured my attention that first time -- how could she now be reduced to sobs at my return visits?

I continued to try to soothe her with my broken Sindhi. One of the other young girls then said to me, “Hooa tawhanji boli na samjhandi.” (--She will not understand your language.)

And I was even more puzzled -- wasn’t I trying to speak to Baji in her own language? Was the girl suggesting that there was some reason why Baji specifically could not understand me, even though the others could? Surely that made no sense.

“Par'a -- chho?” I said in desperation. “Sindhi aahey, na? Maan haaney Sindhi ggaalhayan thee.” (But why? This is Sindhi, isn’t it? I’m speaking Sindhi now.)

“Accha, Sindhi!” said the other girl, seeming content with my response. But I knew that there must still be something that I had not understood. I looked down at Baji, who was becoming calm, though her mood was far from that bright one that had first impressed me. The gears of my own mind were spinning frantically to try to understand what was happening here, and coming up with nothing.

So I let the children lead me on another walk along the riverside. I kept Baji’s hand in mine, determined to make her happy before I left. But she was quiet. The other children chattered with their normal energy, and I heard at least one of them again say that bizarre statement that I had heard before: “She won’t understand your language.”

As I was waiting for Baji to appear, one of the kindly women was sitting with me and trying to tell me about her, but I was understanding very little. The one thing I did understand from her was, “Baji does not have a mother.” I was sorry to hear this, but somehow not surprised. Baji did somehow seem more like an orphan than the other children, in some inexplicable way. But -- could this be the reason why Baji was upset? Now, at this moment? The other things the woman said would probably have helped me understand the whole situation, if only my Sindhi were strong enough.

After a few more minutes, Baji herself did appear, at the arm of another one of the older women, leading her towards me. I could tell from a distance that she was once again in distress -- this time even more than before. I greeted her with a hug, which she didn’t refuse, but also could not really share. In this moment I wanted nothing more than to calm her, but without understanding the problem, I was helpless. I looked at her as gently and sympathetically as I could and asked, “Baaji, chho khush na aaheen? Maslo chhaa aahey?” (Baji, why are you not happy? What is the problem?)

But Baji was not able to answer, still gasping and crying strange, dry tears. I looked to her companions, young and old, and asked the same question. They were all looking on with kindly and untroubled faces. One of the older women did offer the answer, though I couldn’t understand it fully. I caught some of the words she was saying -- “she -- thinks -- take --” but I could not make sense of the whole thought. Desperate for a translation, I looked over the heads of the children to where Papa was standing, some distance away. He was quite absorbed in that phone call, however, and did not hear me trying to call for his assistance. The kindly woman repeated her explanation, but I still did not catch on.

I sat down on a sort of a bench and urged Baji to sit next to me, and I tried to treat her in the most friendly and least frightening way I know how. But I was utterly baffled. This bold, bright girl who had captured my attention that first time -- how could she now be reduced to sobs at my return visits?

I continued to try to soothe her with my broken Sindhi. One of the other young girls then said to me, “Hooa tawhanji boli na samjhandi.” (--She will not understand your language.)

And I was even more puzzled -- wasn’t I trying to speak to Baji in her own language? Was the girl suggesting that there was some reason why Baji specifically could not understand me, even though the others could? Surely that made no sense.

“Par'a -- chho?” I said in desperation. “Sindhi aahey, na? Maan haaney Sindhi ggaalhayan thee.” (But why? This is Sindhi, isn’t it? I’m speaking Sindhi now.)

“Accha, Sindhi!” said the other girl, seeming content with my response. But I knew that there must still be something that I had not understood. I looked down at Baji, who was becoming calm, though her mood was far from that bright one that had first impressed me. The gears of my own mind were spinning frantically to try to understand what was happening here, and coming up with nothing.

So I let the children lead me on another walk along the riverside. I kept Baji’s hand in mine, determined to make her happy before I left. But she was quiet. The other children chattered with their normal energy, and I heard at least one of them again say that bizarre statement that I had heard before: “She won’t understand your language.”

Baji partly consoled.

Baji partly consoled. At some point along this walk, Papa caught up with us, having ended his call. Understandably, most of his thoughts were still in the clinic, with the patients he would soon be seeing. Another fraction of his attention was being absorbed by the bright and buoyant children all around. So there wasn’t much left of Papa’s attention left to explain to me in the kind of depth that I was needing about what was bothering Baji. But I did ask him this question, and after repeating myself once or twice, he asked the same of the others standing nearby. Again I heard the same response I had heard once before, the words I couldn’t quite put together.

And Papa did translate for me: “She thinks you are coming here to take her away.”

And the whole mystery would be unraveled from that simple explanation, though I was too flustered in the moment to see the depth of it.

I was utterly surprised by this idea, so much that I could hardly give it its due. It seemed simply absurd to me. Coming to take her away?

“Baji Baji, sachi naahey,” I tried to say to her, “maan eeain na kandem.” (It’s not true; I will not do that.) But by this point my linguistic skills were highly fatigued, as well as my emotions, and I did not know if she knew what I was talking about.

I wanted to say clearly in Sindhi, “I will never take you away from here,” but I couldn’t manage it -- future constructions are difficult, especially with the complications of a direct object and a location and a compound verb phrase -- I’m still not sure I can manage that whole sentence. (“Maan tokhey kaddahin na kanee eendem, hetan khan…” ? Sindhi friends are welcome to help me with that.)

Suffice it to say that I did not manage to say it clearly. But I also wasn’t yet giving the idea its full weight. It still seemed to me impossible that this could really be what was upsetting Baji. But that was merely because it had not occurred to me before, and the very newness of the idea was keeping me from completely grasping what I should do.

In any case, Baji was looking much less upset by this point, and almost even smiling. “Asaan dost’a aahiyoon, ha na?” I asked her. (We are friends, right?) And she nodded.

“Ain toon khush aaheen? Pareshan na aheen?” (And you are happy? You’re not upset?) She managed another nod and a smile. And I gave her a better hug at this point.

It was clear that Papa needed to get going, and that patients were awaiting him. I was still not fully satisfied that I had communicated well with dear Baji, but I knew that the time for this visit was up. So I said my farewells to all of them.

And to Baji I also said, “Maan wari eendem” (-- I will come again). And I now wish I had not said that -- but only later did I realize why.

As we drove away, I asked Papa if Baji could really have thought I was planning to take her. It still did not seem a logical explanation to me.

“WELL YOU SEE EM,” he replied. “YES. SHE MIGHT THINK THAT. WHEN A FOREIGN LADY MAKES REPEAT VISITS AND WANTS TO SEE HER SPECIFICALLY. SHE MIGHT THINK YOU WANT TO ADOPT HER.”

I tried to let this sink in. “But surely she has no other reason to think so? Wouldn’t the others reassure her that this wasn’t true?”

Papa shrugged. Soon our conversation drifted to other topics, and before long I was again dropped off at the gate of our house in the city.

But my mind was not settled. I could not rid myself of the feeling that I had done something wrong -- not intentionally of course, but something that I still wanted to fix. There is much that I still don’t understand, but gradually over the following days, more pieces of the puzzle were settling in place.

“She won’t understand your language,” the children had said to me. I had thought they meant my Sindhi wasn’t good enough for Baji to understand. But they were not talking about my Sindhi at all -- they meant English, my own language. They meant, “where you’re going to take her, she won’t be able to communicate.” If I had understood it at the time, I could have made things clear. Instead, my answer about speaking Sindhi could only have muddled things further -- making it seem like I was taking her to some place where people speak Sindhi. If only I could have explained that I was not taking her anywhere!

And when the other woman had told me that Baji does not have a mother -- this too feels like quite a different statement, coming from someone who might expect me to be adopting the girl.

And then I began to regret also my last words to Baji, “I will come again.” I meant only that I would continue to visit her, as a friend, and that these visits would always be the same as they had been. And I meant that this was not the last time I’d ever see her, and hoped that she would expect me next time without any distress. But to her ears, I fear that those few words might have had a very different sound. “Maan wari eendem” -- to her, that might have sounded like, “I will try again to take you.”

And I replayed both of my last two visits in my mind, trying to understand what Baji must have been feeling, if she really did expect me to take her with me. Her sobs and her gasps now made sense. She may have been imagining that this could be the last time she would see her home and her loved ones. She was expecting to be torn away from the only world she had ever known. Has she ever even seen a world apart from that riverbank? A child could certainly be forgiven for believing that those vast, calm waters and their stretch of blue sky were the entire universe in themselves. And she was facing the prospect of leaving her entire cosmos and plunging into the unknown.