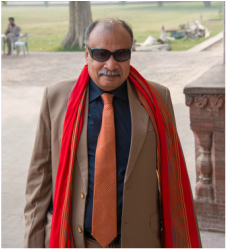

Cool Papa. (After I asked him to hold my sunglasses and dupatta for just a moment) Cool Papa. (After I asked him to hold my sunglasses and dupatta for just a moment) Before padding away down the hallway in his hotel slippers, Papa cast a baffled glance into his suitcase. It had been neatly packed for him by my youngest sister Mehak, who knows all his ways and needs better than Papa himself. But as for what to do with all the stuff in the suitcase -- Papa was once again at a loss. “SWEET EM! WHY DON’T YOU UNPACK ALL THIS FOR ME.” I was momentarily surprised, coming as I do from a “self-serve” culture that values privacy as much as it does independence. Papa’s suitcase was only a small one, containing a few sets of clothes and nothing more, so it would be hardly any work at all for me to unpack it. It was only that cultural attitude shift that took me a split second to achieve. Sensing a moment’s hesitation on my part, Papa continued, “YOU KNOW EM. IT IS VERY SAD FOR ME TRAVELING WITHOUT BOSS.” (“Boss” is what he calls his wife, my Ammi, Saeeda.) “BOSS WOULD DO ALL THESE THINGS FOR ME. OR MEHAKI WOULD. BUT YOU ARE MY ELDEST DAUGHTER AND CAN DO THESE THINGS, TOO.” “I’ll be happy to do that, Papa,” I said. He seemed a bit surprised but very pleased to hear this, and he retired to the other hotel room quite contentedly. I hung those few shirts and pants and jackets of his in the closet, and neatened up a few of his belongings that he had left lying around. It was a very small task, but I could tell that it was very meaningful to Papa to be taken care of in this way. And he was not joking when he said that he was sad to travel without Boss, who in this case had gone to Karachi with one of my brothers for an exam instead of coming with us. Traditional gender roles are very much alive within middle class Pakistani family life, and it is normal for the man of a house to expect his wife or daughters to tend to his domestic needs like this. It often comes as a surprise to me, but at heart I am rather a traditionalist too, and so I usually am happy to fall into my own role as eldest daughter in the Sangi house, with all the responsibilities and privileges that it entails. And for the rest of this short trip, Papa was able to boast that his daughter was taking good care of him. The next morning we were ready again to explore the the historic sites of Lahore. We only had this one day at our disposal, because we were to leave the very next morning for an even shorter visit to Islamabad the next morning. For the sake of protecting my own energies, I insisted that we limit this day’s visits to a small number of sites, and we settled on a few of the most important other Mughal legacies: the tomb of Jahangir as well and that of his wife, Noor Jehan, and the Shalimar Garden.  Intriguing ticket pricing. Intriguing ticket pricing. We arrived on the grounds devoted to Jahangir’s tomb in the late morning, and already the sun had risen towards that glaring midday direction that I so dislike for photography. But after all, every hour cannot be the magic hour, and we cannot save all our sightseeing for sunset. Jahangir’s tomb and its environs nonetheless hold a certain magic that can still be captured at these least magical times of day, and an additional boon was that we had the place nearly to ourselves. Other visitors could be seen occasionally, here and there, but this enormous estate draws a far smaller number of tourists than yesterday’s sights (the Lahore Fort and the Badshahi Mosque). Actually, the estate that I have referred to as “Jahangir’s Tomb” is really a collection of historic sites spread out across a large plot of land in the Shahdara section of Lahore, north of the River Ravi. “Shahdara” translates to “Way of Kings”: this was the preferred entryway into the city of Lahore during the reign of the Moghuls, and an area especially favored by Emperor Jahangir (1569--1627) and his wife and consort Noor Jehan (1577--1645) when they were staying in Lahore. I have not yet been able to ascertain how much of their lives they spent in Lahore -- these Moghuls lived expansive lives across many cities in their Empire -- but Lahore was important enough to both of them that they were buried there, and both of their tombs can be found in Shahdara. Lahore’s other big Mughal attractions (the Fort and Badshahi Mosque that we had visited yesterday) are really not so far away from the Shahdara sites, but they are separated by the river, which seems to have the effect of keeping the less avid tourists on the southern side. We stopped at the ticket counter to pay our entry fare: just 20 rupees for Pakistani citizens, but 500 for all foreigners. Papa tried to argue, as he usually does, that his daughter is also a Pakistani citizen (if an honorary one), but ended up paying the full fare for me anyway. I’m not sure what the logic is behind charging foreigners a price that is *twenty-five times* higher than the local price, but presumably it is simply because they know the foreigners will be willing to pay it, having come a long way to begin with. In any case, 500 Pakistani rupees is the equivalent of only $5, so even this is an extremely good price for the benefit of seeing several historic sites all in one. The first of the sites that one finds right inside the gate past the ticket counter is the Akbari Sarai, which, to the eyes, consists of a pair of large lawns surrounded by a walled arcade, connecting to the tombs of Jahangir on one side and Minister Asif Khan on the other. But that description alone doesn’t quite explain what a “sarai” is, and it is a rather fascinating word, so I hope my readers will allow me a little etymological excursion here. It should be pronounced “sa-raa-ee,” and can be rendered in English alternately as “serai” or “saray” or even with the French “serail” -- which begins to become familiar to many English speakers, who will also recognize the Italian version “seraglio.” The Persian word itself is indeed the same, but the meaning is not. English speakers are familiar with the “seraglio” as meaning a harem in a palace, particularly one associated with Ottoman turks. If we trace that meaning outward a bit, we find it comes from an earlier sense of the Persian word which meant “palace,” but became exoticized to refer specifically to the harem in European imaginations. However, the sense of “sarai” that is relevant to the Akbari Sarai is a different one entirely. After a similar explanation of the palace/seraglio sense of the word, the Hobson-Jobson Dictionary provides this simple definition:

Far from the Orientalist fantasy of veiled harem women, a sarai in South Asia is something closer to a campground, a roadside accommodation. And that is exactly what lay before my eyes at the Akbari Sarai -- although it was a sarai of Mughal proportions. This and the adjoining tombs were built during the reign of Shah Jehan, son and successor of Jahangir. But it is worthwhile to look more closely at the events immediately following Jahangir's death, because this is one of those fascinating points in Mughal history where individual will and intrigue between the royals escalate into a kind of Gordion Knot, finding resolution only in the sword. When Emperor Jahangir died in 1627, he was not immediately succeeded by the famous Shah Jehan, but rather by a different son, Shahryar. The latter had managed this with the help of his stepmother and mother-in-law, who was none other than Noor Jehan, Jahangir’s most powerful wife and consort. Shah Jehan, however, proved the far more ambitious and merciless of the two, and he succeeded in having his brother killed within only a few months of his reign, quickly claiming the throne for himself.  Tomb of Minister Asif Khan. Tomb of Minister Asif Khan. Another strand of the story, complicating the knot of relations between the Mughals, is Jahangir’s Minister, Asif Khan, whom Jahangir had also appointed as Governor of Lahore. Asif Khan was Noor Jehan’s elder brother, but he was also the father of Mumtaz Mahal -- the very same woman in whose honor was built the most beautiful structure of human ingenuity: the Taj Mahal. She was married to Shah Jehan, and her father’s armies were on the side of her husband. It was Asif Khan himself who put the unfortunate Emperor Shahryar to death, on Shah Jehan’s orders, along with several other family members who might also have wanted to threaten Shah Jehan’s reign. Asif Khan continued to have a powerful role in all imperial matters until his own death in 1641. After that, Shah Jehan built him a mausoleum here in this same complex where his own father’s tomb had already been built. And this mausoleum was the building that Papa and I were just then encountering, as our wanderings brought us to one side of the Akbari Sarai. It is a narrow and tall domed structure that must have once looked radiant in the center of its garden plot; nowadays, however, it is one of the more neglected sites in this particular tomb complex. The mausoleum itself appears worn down to the nub; its outer tiles and panels have crumbled, leaving a raw surface exposed underneath. The top of the dome seems to have surrendered itself completely to the forces of nature, sprouting a spiky coif of grass all around--a kind of comical reversal of a balding head. Only in the more protected ceiling areas can you see a trace of the beautiful tile work that once adorned the tomb. The gardens all around are likewise in a state of neglect, overgrown with spiky grass and greyish shrubs. Even there, however, you can still feel the beauty of the landscape, in the form of the elegant and ancient trees that offer their enchanting shade, like this mango tree that stands near the tomb: There was only perhaps one other visitor present at Asif Khan’s tomb when we were there, and also a guard standing watch. The only other figure who walked by was an old man in a strange plaid suit, carrying a sickle. I don’t know what work he was off to do, but there was something interesting in his appearance. I asked Papa to talk to him so that I could take his picture, and then just as quickly he was off on his way, treading his strange diagonal path, sickle in hand. To what use might this elderly man plan to put his sickle? Much work could be done on this lawn, to be sure. Though Asif Khan’s tomb currently lies in a state of profound decay, I suspect that it will see some renovations before too long. It is probably fairly low on the list of priorities when it comes to restoration of such enormous and intricate Mughal sites. Hearteningly, we found many signs of restorative work being done at other parts of the complex. Here, for example, next to the mosque in the Akbari Sarai, a few men were hard at work, repairing damage to the ceilings of the many cells in the outer walls. (As the info sign read, there are 180 such cells in the sarai, so these fellows really have their work cut out for them.) We proceeded back across this sarai in the direction of the opposite large gate, beyond which we would find the tomb of Emperor Jahangir. We paused in the gateway for a few photos against its time-worn bricks and fading frescoes. When I saw the results on my camera screen, I was once again stunned by the evenness of the light. It is only sunlight, and at a time of day when the rays are at their harshest and least flattering -- but when filtered by the graceful architecture of the Mughals, the light falls perfectly upon our faces. Ideal site for a photoshoot.  Hallway to Jahangir's tomb. Hallway to Jahangir's tomb. Looking onward, beyond the gate, we had a fine view of the Emperor’s mausoleum. It was a low rectangular structure with a minaret at each of four corners, all beckoning us from beyond a line of sculpted topiary and now-dry channels that would once have been reflecting rivulets. And Jahangir, I should mention, was not just any Mughal emperor, but the rebellious and libidinous son of Akbar the Great. Jahangir (meaning “world seizer”) is his imperial name, but his given name was Noor-uddin Mohammed Saleem -- and he is the same Saleem who was so vividly romanticized in the movie Mughal-e-azam. (Yes, I confess, my train of thought will always and inevitably return to that movie.) The film's plot, a work of fiction, focuses on Saleem’s immense and tragic love with a court dancer named Anarkali, who is prevented by her lowly station to share a throne with her prince. There is no historical evidence for any actual Anarkali, but her legend persists, and many people in Lahore and beyond will insist even today that this is a true story. The dark and rebellious Saleem/Jahangir is just the sort of historical figure that we love to try to “redeem” by means of a true love. But we will have more to marvel at if we give up the idea of redemption and simply try to comprehend what his life must have been like--if that is even possible. Son of the Great Mughal, sovereign of an enormous empire, possessor of the world’s finest palaces, and husband to twenty wives--who today can even imagine what this life must have been like? All these things I was pondering as we approached his tomb, which became more beautiful as we got closer, and its interior was far more thrilling than the exterior, as it opened to us like a huge jewelry box. The corridor leading up to the tomb itself is tiled intricately in many colors, to glorious effect, despite some missing sections in the ceiling and discoloration in places. To be surrounded by these delicate patterns is mesmerizing, and I was tempted to linger there for some time. But the watchman of the tomb, a kindly older gentleman, scurried along past us, explaining that he was turning the lights on so that we could see the tomb inside, and that we had better come on in before the scheduled load shedding would darken the inner chamber once more. It was kind of the watchman to urge us in this way, because otherwise I might not have gotten to see the tomb in the light at all -- and this is the most beautiful tomb I have yet seen. It is all marble, smooth and cool to the touch, and inlaid with those graceful gem tiles, gleaming in many colors. The upper portion of the tomb is adorned with the hundred names of Allah in beautiful Arabic script. And at the head of the tomb were laid a cluster of fresh rose petals, bright red and mysterious, as if left there by Anarkali herself. As I sat on the rim of this tomb, I felt as if I had been let into the myth itself. I had a wish to whisper to the child version of myself, who had been so enthralled by these Mughal designs in the form of a tiny marble box, that I would some day find myself sitting on a whole bank of such marble. And to tell that child-me that I would be wearing bright colors in an Eastern style, and that this would not be some sort of costume that I would have to change out of in a few minutes, but that they would be my own clothes that I was genuinely wearing for the day, and I would be welcomed into the whole of that beautiful culture. How my young eyes would have widened to be told such an amazing thing! And in truth my reaction to it is still the same today.  Our watchman, after the lights went out. Our watchman, after the lights went out. After a few minutes of those reveries, sure enough, the lights vanished, and we went back out towards the sunlight. Outside on the verandah we found a display explaining a little bit about the restoration work that is being done on the site. I am not in a position to judge how expertly this effort is being carried out--I didn’t have the benefit of an extensive tour of the restoration work, the way I did at the Talpur Mir tombs in Hyderabad--but it seems that they are being done with care and thoughtfulness. Around the back side of the mausoleum we found a large group of artisans and experts chiseling away at their blocks of brick and stone and preparing them to look like the originals. We were also surprised to meet a young couple with a fair complexion and only vaguely Eastern looking clothing exploring the place on their own. We greeted them and asked where they were from--they were British, they told us, and only briefly visiting Pakistan on what was otherwise a trip to India. (As it happens, the only place at which one can pass between these two nations is at Lahore; on the other side of the border is Lahore’s sister city of Amritsar.) This was their first time in Pakistan, and so Papa and I extended them a warm welcome. I told them that they would find people universally kind and hospitable, especially since they were showing an interest in the country’s heritage. They concurred and said that they had had a wonderful experience so far. I felt proud that I myself had become Pakistani enough to have the opportunity to welcome other Westerners to the land. Restoration work on Jahangir's mausoleum.  Cold drinks for the weary traveler. Cold drinks for the weary traveler. Parting cordially from the two young Britons, we went back across the lawn to where we had noticed a large refreshment truck near the gateway. Big Pepsi logos may not match the Mughal architecture very well, but they are still a welcome sight to travelers who have been wandering a long morning around the venerable sites, and we thoroughly enjoyed the ice cream and soda that we got there. And then we were off again -- back to the car, which was necessary to take us the short distance to Noor Jehan’s mausoleum. Viewed on a map, it seems to be nearly on the same site as Jahangir’s, and if I had known to look for it, I might have been able to spot Noor Jahan’s tomb from Asif Khan’s. A railway track lies in between them, however, and some other growth of urban structures, so it constitutes a separate site.  Reminder of the legend of Anarkali. Reminder of the legend of Anarkali. And here we found an even more elaborate restoration effort underway. Enormous slabs of smooth red brick lay stacked all around, as if ready to be pieced into the walls like a great jigsaw puzzle. The exterior walls were already looking quite clean and bright, however, so perhaps these stacked slabs were for interior use. At the time of our visit, the interior of the space was ragged and crumbling (though I always find that ruins are as beautiful as fresh palaces, and sometimes more so). A few men inside were working diligently, spreading some sort of spackling paste into cracks of the wall; perhaps later the red slabs would be applied as an outer layer. I noticed in one direction something that had the appearance of a recently walled-in doorway. This brought to mind Anarkali’s sad end in the Mughal-e-azam legend, and I shared the photo on my Facebook wall with a reference to that. The conversation that followed in the comments thread is a testament to how persistently attractive the Anarkali legend remains in many minds and hearts. But we were not here to think about the mythical Anarkali, but rather the very real, and very impressive, Noor Jehan. She was Jahangir’s twentieth (!!!) and last wife, and the only one who could be considered a true Empress at the side of the Emperor. She was also not the typical young and virginal bride: she was 34 years old and already a widow at the time of marrying Jahangir. (Earlier in this blog post I mentioned the doomed Emperor Shahryar, whom Noor Jehan had manoeuvred into the throne. One of her reasons for this would have been that Shahryar was married to her daughter, Ladli Begum, born of her first marriage.) Noor Jehan’s first husband, Sher Afgan Khan, had been a famous warrior, honored for his service by Jahangir himself. Popular legend has suggested that after Jahangir came to see Sher Afgan’s wife, he arranged for the warrior’s death in battle (very much like the Biblical story of David and Bathsheba) so that he could marry her himself. This story is not corroborated by any evidence, however, and seems all the more unlikely given that Jahangir did not marry Noor Jehan until two years after Sher Afgan’s death. If there is value in that legend, however, it is that it suggests the power that Noor Jehan could wield in the eyes and heart of the Emperor. It was he who gave her the imperial names of Noor Mumtaz ("Light of the Palace") and then Noor Jahan (“Light of the World”). But it was not only his love which made her an important figure: she developed considerable power and influence in her own right, and arguably had greater autonomy and left a greater impact on history than any other woman in the Mughal sphere.  Down we go... Down we go... However, after the death of Jahangir and the brief and tragic reign of Noor Jehan’s chosen protegé Shahryar, Noor Jehan’s own political influence also came to an end. As Shah Jehan rose to power, Noor Jehan lived out the rest of her years in Lahore, in quiet dignity. Some sources suggest that Noor Jehan devoted herself to study, religion, and charity (here's one text, see page 286), until her death in 1645. Papa and I wandered the crumbling interior of the mausoleum, on which restoration work appeared to have only just begun. We inspected the two stones, which commemorate Noor Jehan and her daughter, Ladli Begum. I thought we had seen everything there was to see, when the watchman standing guard started up a conversation with Papa, something about going down to a chamber below. “SWEET EM!” intoned Papa. “LET US FOLLOW THIS MAN.” And the watchman was already sliding open a door from the floor, revealing a staircase headed down toward the crypt. We descended, guided by a very small flashlight in the hands of the watchman, and the weak, narrow beams from our own cell phone lights. To illumine the place falsely with the camera’s flash would have stripped away the eeriness of that dark grotto, so I opted instead to take a few very slow-shutter shots in that impossible darkness, just to offer you all a small sense of the space. Shadowy passages below the tomb of Noor Jehan.  Love bats. Love bats. As we were about to leave the crypt, Papa noticed that we were not completely alone down there: a small family of bats had taken up residence on these low sloping ceilings. One or two of them began fluttering about, uncomfortably close to our heads. “LOOK! IT MUST BE THE GHOST OF NOOR JEHAN,” said Papa. “AND THEREFORE THAT ONE--” he indicated one that had just landed very close to the first bat, “--MUST BE JAHANGIR. TAKE PHOTOGRAPH, SWEET EM.” I dutifully took my shot of the bat couple, consenting for this to use the bright flash. “NOW YOU HAVE GOT PHOTO OF THE ROYAL COUPLE, SWEET EM!” laughed Papa as we climbed the stairs again and emerged into the sunlight. At this point it was time to return to the hotel for lunch and then some rest. I was certainly tired by this time, though Papa is indefatigable, and while I was resting, he circulated among his cardiology colleagues and visited their presentations. By the time I was ready again to go out into the city, it was already dangerously close to sunset. This was a recurring theme for my third trip to Pakistan on the whole: it seems I was almost always racing against the setting sun, hoping to capture more photographs in the last light of day. And that is what happened again on this day when we arrived at the Shalimar Gardens. Not only had the sun already just sunk below the horizon, but the Gardens themselves, we were informed, would be closing to the public in just 15 minutes or so. So we had only this briefest of glimpses at the gardens, which are also a Mughal legacy from the time of Shah Jehan’s reign. And this is one of the few such places in Lahore where you can see the reflecting pools actually filled with water and reflecting the sky. How I would have loved to be there an hour earlier and capture the gleam of the sun against the pearly marble arches, and all the reflected rays! But there was still plenty of beauty to be seen there, even in the dim gloaming. And so I will end this episode of my travelogue with an image of evening falling gently onto the Mughal legacy of Lahore. And here are a few more photos that I didn't manage to squeeze in alongside the text above.......

3 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Image at top left is a digital

portrait by Pakistani artist Imran Zaib, based on one of my own photographic self-portraits in Thari dress. AuthorCurious mind. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

emily s. hauze

RSS Feed

RSS Feed