|

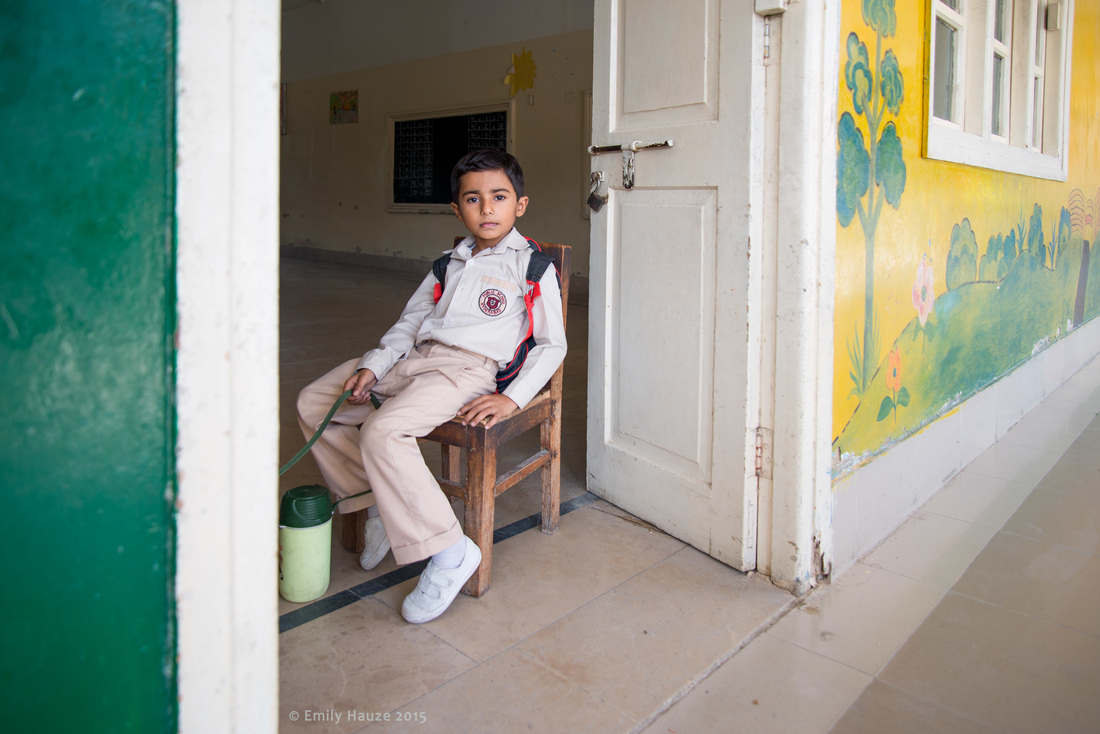

I had slept a bit late on that particular Friday afternoon, and Inam had already left for the office when I came out to have my breakfast. But Inam’s wife, Farzana, tended to me with great care and gentleness, as she always does. Her skills in English are probably only a little better than mine in Sindhi, so communicating together is a good challenge for both of us. I hope my Sindhi will be stronger by the next time I get to see her, but even as it is, we are already able to communicate a fair amount together. On that morning I recall that Farzana told me some beautiful things about her faith. She explained that we are made up of two parts, spirit (rooh) and dust (khak), and that it is the desire of every Muslim for the part that is dust to find its rest in Medina, the Prophet’s city. As for the part that is spirit -- that will be reunited with what is Holy, no matter where the dust comes to rest. These things she told me in a combination of Sindhi and Urdu, as I listened carefully, asking her often to explain certain words. And I sipped my milky tea and ate my fried egg with Sindhi bread, and the two budgies, one blue and one green (or is it yellow?), chattered sweetly in their cage in the corner of the airy living room. As I was finishing up my breakfast, Farzana got a call from Inam, who had been making arrangements for my visit that morning to the Public School Hyderabad. I had two particular reasons to be excited about this visit, namely two people: my adi (respected sister) Shagufta Shah, who is on the senior faculty of the school as an art teacher, and also Priya, Inam’s eldest daughter, who has also been teaching there (in a different section) in the couple of years since her graduation from university. From adi Shagufta I had been hearing about the merits as well as the tribulations of this venerable institution for quite some time. And in my previous trip to Hyderabad, when I first met Priya, I learned about the school from her perspective, though at that stage I had not realized that the school Priya was describing was in fact the same one that I already knew about through adi Shagufta. In both cases I had hoped to visit the school, and so I was all the more delighted when I realized on this trip that the schools were one and the same. The plan now was that I would first go and see adi Shagufta in the senior girls’ section, and she would show me around her part of the school, and eventually lead me to the section for the younger boys, where we would find Priya. Since it was a Friday, which is the holy day, classes would let out around noontime. This meant that I needed to get going quickly -- it was already mid-morning -- if I wanted to see any of the classes still in session. So I grabbed my purse and wrapped myself in my dupatta and started out the door. Farzana pressed a piece of paper into my hand as I left, saying, “Shah sahib khe ddey” (‘give this to Shah sahib’). It was a little note written in Sindhi explaining that the driver should go to the main gate of the school and ask for Shagufta Shah. The driver, whose first name I don’t know since everyone simply calls him “Shah sahib,” was already familiar to me -- he is Inam’s most trusted and reliable driver, so I had no qualms about being taken into the city otherwise alone in his car. But he speaks little English, so it was kind of Farzana to write him a note in case I might have difficulty telling him where I needed to go. Note in hand, I trotted down the stairs of Inam’s house and through the courtyard to where the car was waiting for me. Shah sahib, a soft-spoken man with a gentle face, held the car door open for me and closed it after I had succeeded in gathering my various folds of cloth--dupatta and dress--inside the car. Pakistani readers may wonder why I describe such banal details, but I think my average Western reader will understand what is special about them. In our daily lives we rarely experience these touches of civility and service. The idea of “having a driver” is something reserved only for the very rich, and no one would expect any chivalry from an American taxi driver. Once Shah sahib was situated behind the wheel, I handed him the note and said something like, “Public School halandaaseen.” He looked at the paper and nodded, “Ji ha, madam.” Though Inam’s house is out a little ways from the hustle and bustle of the city, it was still only a short drive to the heart of town where the school is located, via the “Auto Bhan” road. (That road was of course named to suggest the high-speed German Autobahn highways, though the name has been very lightly misspelled. Cars on the Hyderabadi Auto Bhan, however, do not reach such break-neck speeds, as there is simply not enough room on the road for that in this densely-packed and lively city.) When we reached the gate of the main section of the school, we found it guarded by a pair of armed policemen. This is not the least bit unusual -- as I have mentioned in other blog entries, nearly everything in Pakistan is patrolled by armed guards. Although that presents an initial shock to the Western traveler, it is surprising how quickly one becomes accustomed to it, and somehow the guards never seem menacing, despite their heavy weaponry. Shah sahib rolled down the window and asked the guards how he should proceed in order to meet with Madam Shagufta Shah. Adi Shagufta is a well-known personality at the school, so there was no doubt that the guard would know how to direct us. From the glance that he gave me, it seemed possible also that he knew who I was, and why I would be coming -- because through my connection with adi Shagufta on Facebook, I was already fairly well known in this school. He told us that we would find Madam in the Girl’s Section, and pointed us down along the road to a different gate. The school grounds are expansive enough to merit separate entrances to the boys’ and girls’ sections, it turns out. And beyond the senior boys’ and girls’ sections, there is yet another building, devoted to the younger children (elementary school age), which is where we would find Priya later.  Me with adi in the PSH auditorium. Me with adi in the PSH auditorium. Arriving at the second entrance, we inquired with a second set of guards, who told us we would find Madam Shagufta just beyond a nearby entrance. Shah sahib got out of the car to accompany me in case I had any trouble, but it turned out to be hardly necessary, because I spotted adi Shagufta through a window, in a front office, and we both waved excitedly as she hurried out to greet me. “Hoo’a munhnji pyaari adi aahey,” I explained to Shah sahib (‘she is my dear sister’), as she came out to give me a warm hug. It is a wonderful feeling to be welcomed into a new place where you are nonetheless already known and loved. I always feel proud in such moments -- especially if there are guards or other onlookers who might naturally be a bit suspicious or curious about what an outsider like me might be doing there. The mood always changes when I am greeted by those who know me -- and few could greet me with more love than my dear sister Shagufta. As her guest, I would command all the same respect that she does. She handed me a bouquet of bright flowers, beautifully bundled -- mostly blossoms of bougainvillea, I think, though somehow I didn’t manage to keep a picture of them. I do recall that they had been gathered and arranged from right there on the school grounds by one of the gardeners, and that they do that regularly for honored guests. Tending to those expansive school grounds is a large job, adi Shagufta told me, and the gardeners on staff work long hours and are paid very little, but still they put a great deal of love into their work. The campus is indeed lined with many flowering bushes and graceful trees, tended by the same hands which had prepared my bouquet. At this point we exchanged the same kinds of loving pleasantries that one might expect -- along with an exchange of gifts -- my Sindhi friends are generous beyond measure, and adi Shagufta is especially so. She gave me some beautifully stitched clothes (a dress and more), and a locally made dupatta, which she was pleased to see matched the simple traditional dress that I was wearing at the time. So I pulled off the dupatta that I had been wearing and replaced it with the new one, which you’ll see here in the photos. I gave her a diary sketchbook, because I know she is fond of sketching and thought she might like to record her visual thoughts in this way.  But we knew we should not spend too long chatting and giving gifts, because we wanted to see the classes before they let out for the day. As we set out into the hallway, we were joined by a tall and smiling woman who at once gave me a big hug, though I did not recognize her. “This is Asma,” said adi Shagufta, “but you know her already as Assyed Syed.” “Oh, of course! So nice to have a face to go with your name,” I said, and returned her hug. She was indeed known to me on Facebook, but she like many other Pakistani women does not use her own photograph on her profile (or even her precise name), which is why I had never seen her before. The reasons for such privacy among women on Facebook are complicated and varied -- sometimes it is societally induced, sometimes it is the behest of a father or husband that a woman not show herself, and sometimes it is simply modesty. I’m not sure which of these reasons keeps Asma from sharing her own picture online, but out of respect for it I will not share any pictures of her, even though she was our companion for the rest of this visit. (Adi Shagufta, meanwhile, has been very progressive in her stance on photographs online. For one thing, she knows that she is a public figure -- she is well-known in Sindh for her writing in many genres as well as for her artwork -- and she does not feel the need to keep her face hidden, and most of the time she does not cover her head with her dupatta. That does not mean, however, that she lacks modesty; she is instead a fine example of a different way in which traditional Islamic modesty can combine with more progressive and liberal views.)  Assalaam-o-alaikum! Assalaam-o-alaikum! We proceeded down a short corridor and towards a central courtyard, around which the girls’ classrooms are arranged on two levels. Like so much of the architecture in Sindh, there is a fluidity between what is indoors and what is outdoors. In a climate in which it is rarely cold or rainy, the focus is always on maximizing coolness and airiness. Behind windowpanes we could see the girls at their desks, writing and watching and listening. Perhaps they were doing these things less intently at this hour than they might have been earlier in the week -- after all, what schoolchildren don’t get excited about the imminent arrival of the weekend? But I didn’t notice any tell-tale signs of distraction or giddiness. The girls seemed focused on their learning. “Would you like to meet the students?” adi Shagufta asked me. I answered “of course,” and so we strolled right into the first classroom. To my great surprise, the students all stood up at once as we entered, and said in a slow and rhythmic unison: “Assalaam-o-alaikum!” “Walaikum assalaam,” I responded, no doubt smiling broadly. I realized at once that this must be a school custom so ingrained as to be completely automatic for the students -- but for me, such elaborate displays of respect and discipline are still a source of amazement. A group of young American students might be induced to say “good morning Mrs. So-and-So” on command, but only sometimes, and usually grudgingly. But for them to stand up immediately upon a guest’s entrance into the room and offer the greeting cheerfully -- that would be extremely unusual. The girls all wear uniforms -- which is not unheard of in American private schools, though it is very uncommon. In Pakistan, however, school uniforms are nearly universal, and from what I’ve seen, they seem quite similar from school to school. At PSH, the girls wear a simple grey suit with white shalwar pants and a white stole, with the option of a hijab over their heads. Most girls I saw, perhaps surprisingly, did not cover their heads -- but since only women were present (apart from a few male teachers), there must not be much pressure to do so. (Notably, a much higher percentage of veiled heads is visible in my photograph of a math class, whose teacher is a man.) A sensible pocket at waist level bears the crest of the school. Under the grey kurta is a white blouse with a rounded collar and scalloped edges, which are visible both at the collar and on the cuffs, and which add a certain softness and quaintness. It seems to me these are also marks of Englishness -- and certainly the educational sphere is one of the places in which colonial heritage can be felt most strongly. I was first introduced to the teacher, who greeted me with a hug and did not seem to mind our interruption of her class. Then adi Shagufta turned to the class and introduced me to the girls. “Many of you will already be knowing Ms Emily Hauze from Facebook, especially if you are connected with me there,” she said. Many of the girls smiled and nodded. “Do any of you have any questions to ask Ms Emily? A blush of shyness came over most of them, but one girl in a middle row piped up, “Do you like Sindh?” To which I explained what my blog readers will already know well, which is that indeed I love Sindh and it is a second home to me. The girls giggled contentedly at my response. We repeated that same pattern of meeting-and-greeting in several other classrooms, and in each one I was pleased to be met with the same charming salute of “Assalaam-o-alaikum” from the students. We had a peek also in a couple of science labs, not currently in use. The chemistry lab was enchanting to my eyes -- very old-fashioned in appearance, with ancient-looking bottles of chemicals lined up on carrell shelves. There is something both good and bad to be said for the “modernizing” of classrooms. A comparable American chemistry lab would be fitted out with more digital devices, and any bottles of chemicals would be stored away in locked closets as per safety codes. The students might be able to perform more accurate experiments, and more safely, in the American setting, but at the same time, very few of the students would feel the magic of it--and the net result of learning is probably no higher. The older-seeming equipment of the PSH laboratory carries a hint of excitement, an invitation to learning and experimenting. For higher education, more advanced equipment would certainly be necessary -- but for the level of science needed to get teenagers interested, the chemistry lab I visited seemed ideal. I hope that the young women of Public School Hyderabad are indeed being inspired to advance in scientific fields.  Prefects display a fine sash. Prefects display a fine sash. A little further down the hallway we came to a classroom in which some of the older girls were gathered for their last class of the day. As before, they all stood up to greet me, and remained standing until I had left. Among this group I saw that a few of the girls wore sashes across their kurtas indicating that they were Prefects (or the Head Prefect, Deputy Head Prefect, etc). This also caught my eye as something very different from American culture, at least as it was in my own youth. Although we had an Honor Council and a group of student Proctors in my high school, and it was a source of pride to be in either group, we never wore any kind of badge to announce the privilege, even if we secretly would have liked to. For us, high school years were all about blending in with the crowd and trying to be as un-unique as possible. A sash announcing a special status would have quickly become a point of derision and mockery (disguising the other students’ jealousy). It seems to me that in Pakistan, by contrast, rankings of this kind are held in more genuinely high esteem, and that a Prefect is someone who commands a degree of respect, rather than jealous mockery.  Craftwork gifts, student-made. Craftwork gifts, student-made. And finally we arrived in a hallway that was already very familiar to me from adi Shagufta’s Facebook timeline -- her art department. Some of the younger girls were in an art class at that moment, and we said a quick salaam to them before going to adi’s own office-studio at the end of the hallway. It is a large open space with a desk in one corner near the windows, which look out on adi’s familiar view of the open field and the ceramic-tiled roofs of the school building. The walls are lined with student art projects (and also some of adi’s own drawings), arranged neatly with a gallerist’s sensibilities. One long table at the left side of the room was covered with student craft projects -- purses, fans, and other decorations designed loosely with Sindhi traditional themes and young girls’ imaginations. Adi told me that these were to be given to guests, and that I would be welcome to take any of them. Trying not to linger too long on my choice, I picked out a small and simple purse and an ajrak-patterned fan. On the other side of the room was a cabinet containing more student creations: decorative boxes and dolls and vases filled with tiny arrangements of colored baubles suspended in gel. I was offered any of these that I might like as well, but, worrying for the weight of my suitcases, I had to decline. (I try to leave space in my suitcases for gifts whenever I travel to Sindh, but I invariably end up filling them to the brim nonetheless, because of the extraordinary generosity of Sindhi people.)  Junior's Section, exterior. Junior's Section, exterior. By this time, classes had all let out, and the building was gradually becoming quieter and more empty. I asked if we ought to be heading over to the Junior Section, where Priya would probably be waiting for us. There was some deliberation as to whether we should find our driver or simply walk there, but it is actually a very short distance, so adi and Asma did not argue when I urged that we should walk. In the hotter months, I’m sure that even that small walk can feel like a trek in the beating sun, but on this day we walked comfortably together down the broad alley and then across a grassy path which forms a short cut to the boys’ section and the junior section, both set apart from the girls’ section. The area around the Junior Section is charmingly landscaped, with sculpted hedges and immense flowering trees that blanket the building itself in their colorful shade. A few children were milling about, meeting their parents, but mostly it was quiet. We inquired inside at an administrator’s office as to where we might find Miss Priya, and were told that she was in a meeting with the principal.  Peeking Juniors Peeking Juniors So we continued to wander. I found that the Junior Section is also arranged around a central courtyard, though the classrooms comprise only a single storey on all sides. The corridors facing onto the courtyard are lined with rounded pillars, some of them painted in bright colors, and interspersed with hanging flowers. Some of the walls are painted with fanciful scenes. Though most of the children had left, a few giggling faces peered out at me from an open window along one of the walls. Luckily I was just quick enough to snap their picture before they vanished again into their classroom. Down a little further, I found another boy, who was sitting on a chair in the doorway of his classroom, waiting for his parents. He was an especially beautiful child, sitting perfectly still, with a wistful and air of quiet around him. He didn’t seem to mind as I knelt to take his photo, and his expression remained peaceful. I wondered what sorts of childhood stories might be playing in his mind as he remained statue-still there in his chair.  Soon we left the Junior Section and continued to the Boys’ Section, which is the oldest of the buildings, and features the imposing clock tower, which has become a symbol of the school. On our way, however, I was in for a surprise, when Asma asked if wanted to see the Zoo! A school zoo? I wondered, never having encountered such a thing. But there indeed it was, another enclosed courtyard lined with cages containing a few animals -- mainly a monkey, but also some colorful birds, and many geese and ducks wandering around the center. I told my companions that if there had been a zoo at my own school, I probably would have spent countless hours there.  hikro ddingo bholrro. hikro ddingo bholrro. Even in this moment I was tempted to linger in the little zoo, communicating with that solemn monkey who watched us knowingly from his cage. At one random moment the monkey burst forth with a huge shout, causing us three women to jump in surprise and then burst into laughter. Asma explained that he always does that, and that he’s a very naughty monkey.  Quick glimpse of the Boys' Section. Quick glimpse of the Boys' Section. We did not hover too long in front of the monkey cage, conscious of the advancing hour. We made our way onward to the Boys’ Section, where Priya had been meeting with the Principal. She was just getting out of that meeting as we arrived. I introduced Priya to adi Shagufta -- the two of them knew each other from a distance, but hadn’t had any real contact, since they work in different sections of the school. I felt pleased to be a connection between these two women, coming as I do from all the way on the other side of the world. And when Priya mentioned a bit later that she had in fact always been an admirer of Shagufta’s, having read and loved her novels years ago, my own feeling of delight at connection rose even higher.  Principal's office. Principal's office. By this time word had also reached the Principal that a foreign guest was here on campus, and we were all invited into his office for tea. Principal Muhammad Youssef is a distinguished-looking gentleman with a love of literature and considerable eloquence in speaking English. I hardly needed to introduce myself, because it turns out he knows Papa Saeed, though I can’t now remember what caused their paths to cross in the past. Soon after we sat down, a servant appeared carrying slim glasses with two kinds of sugary juice, one green (lime?) and the other an almost milky white (lemon?), Pakistani colors of course. Tea followed soon after, and I apparently proved myself as a ‘true Sindhiyani’ in the eyes of Principal Youssef when he saw me automatically dip my cookie into the tea before taking a bite. Certain customary behaviors come to me instinctively, I explained to him, and in other cases they come from close observation--and when I pull it off successfully, there is none more pleased than I. And, once again, my recounting of a visit ends in a moment of shared tea and Sindhi hospitality. (After this short meeting with the Principal, we all piled into Shah sahib’s vehicle once again, and he dropped adi Shagufta and Asma off at their respective homes before delivering Priya and me back to Inam.) In this case, however, I am aware that I haven’t told the whole story, and the omissions weigh heavily on my mind. I have not intentionally obscured any harsh truths, but have perhaps avoided them out of an excess of caution, because I do not yet know enough about them to evaluate them fairly. What I am hinting at here are problems in the administration--issues of corruption and ineptitude, which are common to all levels of Sindhi bureaucracy to varying degrees, and education is an area in which corruption is especially deep-seated. I was told by various teachers at Public School Hyderabad, for example, that they often have to go without their own paychecks for months at a time, not due to an actual shortage of funds but due to some administrative inability to allocated the funds at the right time. Months with no salary at all -- and the salary that they do receive is extremely humble, even though they are teaching in one of the most elite schools in the second-most important city in Sindh. One can only imagine what injustices, by comparison, are faced by teachers and staff at schools of less privilege. Further there is a history of nepotism and cronyism and unfair hirings and firings -- all the same pains that chronically afflict so many areas of life in my beloved Sindh. So why didn’t I spend more time talking about them here in this surprisingly long account of my visit? Two main reasons. The first is that I simply do not know enough about them to speak authoritatively -- I don’t know who is to blame, I don’t know the extent of the problems, and it would take a lot more investigative journalism than I am capable of doing in a 2-hour visit in order to report fairly on them. And secondly, I don’t feel that investigative journalism of that sort is my main purpose. I do not like to turn away from harsh realities -- but nonetheless, my inner calling is to celebrate what I find in Sindh. The problems are everywhere -- I can’t and don’t want to hide from them. But still I love what I see. I love what is shown to me. At Public School Hyderabad, I saw dozens of beautiful young faces whose eyes were bright with learning. I saw teachers who work hard to offer the gift of knowledge to those young ones who come to them. I saw gardens tended by unseen hands of gardeners who get paid almost nothing, yet keep countless flowers blooming. I saw cleanliness and discipline and passion and creativity. Perhaps in the future I will have cause to investigate the problems of the school or other educational institutions more deeply. For now, my primary message highlights what is going well: learning is alive. Additional photos from Public School Hyderabad:

7 Comments

|

Image at top left is a digital

portrait by Pakistani artist Imran Zaib, based on one of my own photographic self-portraits in Thari dress. AuthorCurious mind. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

emily s. hauze

RSS Feed

RSS Feed