|

“SWEET EM! YOU ARE GOING TO HAVE THE TIME OF YOUR LIFE,” said Papa Saeed into the phone. I was still in Hyderabad, scurrying to get myself put together to go on the day’s field trip. I had just told Papa that Inam and buddies would be taking me to see Makli and Thatta, which are neighboring towns about two hours southwest of Hyderabad. “YOU WILL BE AMAZED AT THE HISTORIC SITES. YOU HAVE NEVER SEEN ANYTHING LIKE MAKLI. TAKE MANY PHOTOGRAPHS, SWEET EM.” This was the second full day of my second trip to Sindh. My previous two blog entries describe most of the first day -- my welcome in Hyderabad by my dear friend Inam Sheikh and his family, the assembling of buddies, our visits to sites within the city of Hyderabad -- but even they do not describe all that had already happened since my arrival. On that first night, for example, I was honored with a gathering of extraordinary Sindhis who met me for dinner at the Hyderabad Gymkhanna, organized by the prominent intellectuals--whom I am proud to call my friends--Jami Chandio and Sahar Gul (who is Jami’s wife, but also a highly respected academic in her own right). Jami and Sahar had gathered a room full of Sindhi luminaries to meet me--men and women in equal number--writers, anthropologists, psychologists, activists, journalists, and others, including my dear adi (sister) Shagufta Shah, who had also greeted Andrew and me on our first day in Sindh on the previous trip. I wish I had recorded the proceedings as these guests introduced themselves to me one by one around the room. Rarely have I been in such thoroughly distinguished company -- each one of them far more accomplished than I. Each day I spent in Sindh seems to have been stuffed with several lifetimes’ worth of experiences, which expand across many pages when I try to unravel them for this blog. But now I shall move on to that second day of the second trip. After having breakfast with Inam’s wife and daughters, who are themselves so charming that I could have happily spent the whole morning chatting with them, Inam told me that a few of our buddies from the previous day had again gathered and were ready to depart. I think there were five of us -- Naranjan, Rafiq Chandio, Mohammad Khoso, Inam, and myself, plus a guard and maybe another driver, and we would be joined by several more buddies in the afternoon at Thatta.  Our first stop: a mysterious terrain. Our first stop: a mysterious terrain. We left Inam’s house in two cars, and for the first leg of the journey, and conversation was lively, such that I almost didn’t notice when we suddenly stopped in an unusual expanse of desert-like terrain. And I am not entirely sure what this place was. I think it was an enormous burial ground--it certainly looked like that--but it looked to me like something from another planet, with its strangely arranged jagged stones, organized and yet seemingly organic, like the stones had arranged themselves there on their own. The whole place been both immensely eroded by the sands and winds of time, as well as oddly compacted onto itself, its obelisks and memorials all gathering closer and closer to one another like a contracting galaxy of stars. If this place was explained to me at the time, I can’t recall the story -- perhaps Inam can fill us in on this, if he reads this blog entry. Or perhaps it is more charming to remember it as a mysterious alien graveyard. But that was only a quick stop on the way--it was not the main destination. After the requisite photo-taking, we buddies re-shuffled our car arrangement and continued on toward Makli. This place towards which we were headed was also a graveyard, and also a ruin, but something on a very different scale from this first wasteland. Inam did try to explain to me, in vague terms, what we were going to see. But I suspect I still had little concept of what it was until we actually arrived at the Makli Necropolis. True to its name, this is not merely a graveyard, but a “city of the dead” (necro+polis), and one of the largest of these in the world. It is a silent city, consisting of miles of tombs and monuments erected in the memory of countless rulers and nobles and saints of Sindh. By some estimates there are as many as half a million graves, though of course not all of them are grand mausoleums. Nonetheless, there are many mausoleums, grand and grander, old and older, in varying states of erosion under the Sindhi sun. Researching the site after the fact, I found this little gem of a paragraph in a BBC travelogue, which I think bears sharing here:

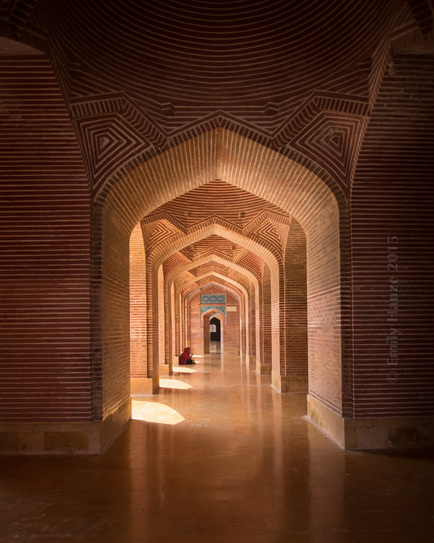

There is still something ecstatic in the air in Makli, though it is a diffuse kind of ecstasy, spreading itself across the vastness of this airy, sandy space. To drive around the Makli necropolis is a strange thing. It is something like driving around a ghost town, but the bright sun against the arid landscape (at least for visitors at midday) inoculates the place against any feeling of spookiness. Like most historical sites in Sindh, there has been only minimal work done to restore and preserve the Necropolis for future visitors, and only a few of the mausoleums we saw were marked with explanatory signs. What signs there were tended to be crumbling and difficult to read, especially for me, with my limited Urdu abilities further slowed down by the need to decipher half-vanished characters. (Memory may serve me wrong, but I think the signs were more frequently in Urdu than Sindhi.)  Inside the tomb. Photo by Inam. Inside the tomb. Photo by Inam. Fortunately for me, Inam and my other buddies were able to identify many of them for me. There was, for example, the tomb of the sultan Jam Nizamuddin II, with its elaborately scrolled facade. I couldn’t help but feel I was entering a temple or a holy place, but was reassured by my buddies that because this man was a king and not a saint, it wasn’t necessary to treat the tomb as a shrine. Thus it wasn’t so essential to remove shoes and keep my head covered--though the pictures will affirm that I did that second part anyway. At the even more palatial tomb of Essa Khan Tarkhan, however, I allowed the dupatta to slip from my head as I wandered in and out of the shadows on those beautiful verandas. I will allow the photographs to tell the story of Essa Khan Tarkhan (see the slideshow below), but I want to linger a moment in the vicinity of the tomb of Jam Nizamuddin for a moment longer here. Neighboring that stately mausoleum were many others in partial or complete ruin. There was a gazebo looking out onto the desert expanse in one direction, and toward the gleaming whiteness of a distant mosque in another direction. There was a structure with four tall but crumbling walls, in which some hardy leafless trees had taken up residence, stretching their wooden arms out the open windows. Down the dusty drive was a low-lying, fort-like structure, and on and on in the distance were more tombs. Scattered variously were a few defiantly erect but inscrutable stones, once signifiers of something, someone.  An encampment in the distance. An encampment in the distance. And just a little farther in the distance, at a remove from the road on which we few visitors travel, a breezy flutter of motion caught my eye. It was the flapping of worn cloth at the edges of the tent-like cabins set up by nomadic people who live here. I could see a little settlement, ringed with a fence made of rough, interlacing branches of desert trees. A couple of billows of smoke rising from makeshift stoves ensured that this was an active homestead, and not a ghost town. So there is in fact life, human life, here in this City of the Dead. It is a far cry from the kind of life hinted by the elegant mausoleums of the past kings and nobles -- destitute, colorless, lacking any hint of luxury. The only thing that these settlements appeared to have in common with the royal mausoleums is their complete estrangement from the advancement of the modern world. As we rolled back across the gravelly roads, Inam told me that we were going to see a special shrine before leaving Makli. “There is a legend,” he told me, “about the shrine of Abdullah Shah Ashabi. They say that there is one minute in the day during which any wish that you make will be granted. So you will go in and make a wish.” I raised my eyebrows in amusement and intrigue, and a broad grin spread across Inam’s face. “Who knows!” he said impishly. “Hahaha…..Maybe you will land on the right minute.”  The shrine of Abdullah Shah Ashaabi. The shrine of Abdullah Shah Ashaabi. The shrine of Abdullah Shah Ashabi is so unlike the other parts of the Necropolis that we had seen that it is hard to believe, in retrospect, that it is part of the same larger structure. I had to check on Google maps to make sure that memory wasn’t deceiving me. Where the other tombs and monuments tended to be of unpainted stone, ornate but austere, this shrine was a bright starburst of carnival colors, particularly a dark lime-green, against which white trimming pops out to greet the eye. Here also there is flapping cloth -- not rags and tatters, but crisp-edged flags and banners in all colors. We entered through a gateway that was closely lined with vendors of sweets and trinkets. The sudden swirl of colors and people distracted me such that I almost passed right by the place where we were supposed to deposit our shoes. Our guard called to me with gentle urgency, “Mem!” and pointed to the rows of empty shoes, and I added mine to the ranks.  Inam at the shrine. Inam at the shrine. Inam was looking at his watch. Time was getting away from us, and there was still a lot that he wanted for us to see before the day was done. But he was still intent that I get my chance at wish-making in this special shrine. We approached its entrance and peered inside to where the shrine lies behind a metal grille. Several womenfolk were waiting outside, and I soon realized that this was because women were not allowed inside. As Inam made a gesture to tell me, ‘go! go on inside,’ someone approached him to remind him of the no-women rule. I wouldn’t have argued the point -- preferring to bow to local customs -- but Inam came to my defense. “She is a foreigner,” he was saying. “It’s okay, she’ll just step inside.” Thus buttressed by my friend’s support, I first made eye contact with the concerned man to try to express my innocent intentions, and then followed Inam’s gesture and ducked inside the shrine. I went inside and acknowledged the saint, and after a moment I scurried back outside to where Inam was waiting. “Did you make your wish?” he asked. I nodded. He didn’t ask what the wish had been -- and it seems to me that, in solidarity with the saint, I should not reveal it. That small mission accomplished, we left swiftly so that we could see one more historic site before our mid-afternoon lunch at Keenjhar lake. For this we left Makli for the neighboring town of Thatta, which I gather is a separate town from Makli, but also is the name of the district, so all of these sites can be thought of as being within Thatta in a sense.  Shah Jahan Mosque: Mughal grace in Sindh. Shah Jahan Mosque: Mughal grace in Sindh. Anyway, this next site is particularly dear to my heart, because it is the first actual exemplum of Mughal architecture that I have visited in person, having all my life been enchanted by that style (knowing, as any Westerner does, the beautiful curves of the Taj Mahal, if nothing else). The Shah Jahan Mosque in Thatta is not as opulent as other Mughal-era mosques or palaces, but it still its lines fall into those graceful geometries that seem to have been the secret wisdom of the Mughals alone. And this mosque bears the name of the same Mughal Emperor who famously commissioned the great Taj itself. Shah Jahan (1592 - 1666) is not the most admirable of the Mughals in terms of his politics or humanitarianism--but this short blog entry is not the place to delve into his biography (perhaps another time!). Suffice it to say here that he has a complicated legacy, but is nonetheless the imperial force behind some of the greatest architecture of our world. And one small piece of that architectural legacy happens to lie in my own beloved Sindh. Apparently, Shah Jahan built the mosque as a gift to the people of Thatta for having sheltered him during a period of exile before his reign (according to this useful article). And it is unique, to my knowledge, in combining that Mughal grace with the warmth of local Sindhi craftsmanship. The angled corridors are built of red bricks and the domes and arches are inlaid with colored tiles that likely come from Hala, Sindh’s home of decorative arts. Again I had only a few minutes to try to capture this beautiful place in my lens and in my memory. But I recall the sense of quiet and coolness -- having arrived at a time in between prayers, with only a few visitors and worshippers sharing the space in wordless calm.  Ablutions at the mosque. Ablutions at the mosque. By this time it seemed that most of my buddies had tired of sightseeing, or were feeling compelled to answer the call of duty on various phones and smart devices--it was a working day for most people, after all. Inam had been staunchly guiding me through these sites as the others gradually dispersed to shady corners to tend to their business. But now the group reassembled in its fullness for our lakeside lunch -- in fact, in greater fullness than before, because several friends who had not been with us at Makli were waiting already for us when we reached Keenjhar. A bright circle of buddies was waiting for us there, including dear Naz Sahito and Jami Chandio, who had not been along for the earlier part of the day. And beyond that several more smiling faces, whom I could not identify.  a young boatsman at the edge of Keenjhar lake. a young boatsman at the edge of Keenjhar lake. At this part in the day, as so often happens in these tales I recount to you readers of my blog, I was becoming quite sleepy, still not remotely over the jetlag of the plane journey (just two days earlier), and quite apart from that I would have been a bit tired anyway from a day packed with sightseeing. I rather enjoy the way that sleepiness blurs my memories of this part of the day, though, putting a bright haze on top of everything. We all sat there at the lakeside, a large ring of buddies in white plastic chairs, and tea was brought to us… that must have been after our lunch, but I can’t recall exactly. I do recall allowing my eyes to droop a bit as I listened to the chattering of my friends with one another, almost entirely in Sindhi. The more I listened, the more I could understand, though I was (and am) still quite a long way from a true grasp of the language. But on a sleepy afternoon like this, I was content to let those gentle sounds wash over me like the murmurings of the lake itself. It is a very rounded and gentle language, extremely subtle in its consonants, never jarring or jagged. So I was happy to relax a bit, as much as my little plastic chair would allow, and listen to the light banter of my friends. Whenever I would open my eyes, I would be met with that bright shining of the lake itself, which at mid-afternoon can be almost overwhelming. Until my sensitive eyes readjusted, it felt like Keenjhar Lake was filled with only gleaming white light instead of water. After this short respite we soon piled back into our cars to drive back to Hyderabad, where another event was planned for the evening -- a concert of traditional Sindhi music arranged for me at the radio station, where several of our buddies work. I will try to make that--and the wonderful topic of Sindhi music more broadly--the subject of my next blog entry. But though on that day we swiftly left the lakeside long before the sun began to set, I will linger at Keenjhar a little longer in my writing here, to end this chapter of my travelogue. At one point as we were all sitting there in that circle, I do recall asking my friends to tell me more about the stories of this fabled lake. And when telling the story they began to glow as well, perhaps because the historic legend that accompanies this lake is the only one of the great love stories in Shah Latif’s account that does not end in tragedy. Most of Latif’s legendary Sindhi queens are fated to be separated from their beloveds, sometimes losing their lives in trying to reunite with them. But Noori from Keenjhar was blessed with a gentler fortune. She also was not born a queen: she was a simple fisherwoman, but she was known among the locals for her grace, and she was called Noori (divine light) because she was radiant like the full moon. Still, she never expected that she might catch the attention of a King. But on one fateful day she was sighted by Jam Tamachi, a King of the Samma dynasty, and he instantly fell in love with her. Strengthened by that love, he liberated himself from societal rules concerning rank and station, and he made Noori a Queen above all other queens. Thus elevated, however, Noori never forgot her origins, and never wished to ornament herself in luxury. Her humility drew Jam Tamachi even closer into their love. Thus the story of Noori and Jam Tamachi has become a symbol of spiritual union, a transcendent marriage of souls. Noori is believed to be buried, upon her wish, in Keenjhar lake -- and perhaps that is the reason for its unusual glow.

Below: more photos from Makli and Thatta. Many are the same as the above, but there are extras as well. I took all the photos except for the ones of me, which were taken (quite expertly) by dear Inam.

7 Comments

|

Image at top left is a digital

portrait by Pakistani artist Imran Zaib, based on one of my own photographic self-portraits in Thari dress. AuthorCurious mind. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

emily s. hauze

RSS Feed

RSS Feed