|

| *I think it’s important to note that this lack of poetry and lack of rhyme is specific to my white-Protestant upbringing, and I would have had a very different perspective had I grown up instead with the hip-hop and rap poetry of Black America. That is a culture in which poetry is as alive and vibrant as anywhere I can imagine, and in which the idea of rhyme has reached new heights of virtuosity. But that is not the culture in which I grew up. |

Hearing Sindhi poetry recited reminded me much of the life of a poem is in its music: in the way in which it sounds and dances in the mind, whether that be in a traditional rhyming meter or an unrestricted free form. If that music were not essential, then the Meaning could be just as well expressed in prose, in paragraphs. Thus the “Essence”, which is what all translators really want to capture, is not in the “Meaning” alone. It is also not to be captured in the form alone, nor in the style. That intangible Essence refuses to be even described, let alone defined. It is like trying to bottle the scent of a rose directly from the air. It is entirely impossible.

And yet, there are few reactions more frustrating to receive on a translation than that old chestnut: “Somehow it just doesn’t capture the essence of the original.” There is no way to argue against this criticism, because it is invariably correct. The Essence is not available for bottling and re-selling. And so, how to respond to that critique, other than to say: “I tried my best -- and I will keep trying” -- ? My best hope can never be to convey the true Essence, but simply to limit the pain of its loss.

And having recognized an inevitable loss, how should the translator behave? In academic circles it has become trendy to debate whether translation is really an “act of brutality” against an original text. Although the word “brutality” seems a bit extravagant, the idea is really not far removed from comments received about a translation “not capturing the essence.” According to this thinking, the translator is doing something unnatural and unkind, mutilating a work of genius by sending it through a linguistic shredder and offering the results as if they were still whole. And that is an engaging idea -- until one remembers that the translator has actually done nothing at all to the original poem. It has not gone through any shredder: the original poem still exists. There was no attack and no dismantling, and more importantly, no replacing. The translation wishes to emulate, but not to dethrone, the original.

It seems to me that the best way to think of a translation is as a bridge. The original poem has its place, its home, in its language. All those who know the language have access to the poem, but it is out of reach for all others -- until someone builds a bridge. That bridge must start from the native language of the translator, who undertakes the task to connect the new reader to the original. The better the translation, the more solid the bridge, and the more likely it is to transport new readers back to the source. A poor translation requires much from the reader, much clinging and perseverance, if he wishes to understand the poem, and many will be lost along the way. A fine translation, by contrast, will allow the new readers to pass smoothly as if traveling in their own country, and yet experience something they couldn’t otherwise see. The strongest bridge of all is that which inspires the new reader to try to learn the language itself, so that he can approach the poem in its genuine Essence.

And so, that is my project, however long it takes me -- years certainly, or a lifetime, perhaps. I hope I can build a sturdy bridge for future travelers. All pilgrims are welcome on the road toward Bhit Shah.

And yet, there are few reactions more frustrating to receive on a translation than that old chestnut: “Somehow it just doesn’t capture the essence of the original.” There is no way to argue against this criticism, because it is invariably correct. The Essence is not available for bottling and re-selling. And so, how to respond to that critique, other than to say: “I tried my best -- and I will keep trying” -- ? My best hope can never be to convey the true Essence, but simply to limit the pain of its loss.

And having recognized an inevitable loss, how should the translator behave? In academic circles it has become trendy to debate whether translation is really an “act of brutality” against an original text. Although the word “brutality” seems a bit extravagant, the idea is really not far removed from comments received about a translation “not capturing the essence.” According to this thinking, the translator is doing something unnatural and unkind, mutilating a work of genius by sending it through a linguistic shredder and offering the results as if they were still whole. And that is an engaging idea -- until one remembers that the translator has actually done nothing at all to the original poem. It has not gone through any shredder: the original poem still exists. There was no attack and no dismantling, and more importantly, no replacing. The translation wishes to emulate, but not to dethrone, the original.

It seems to me that the best way to think of a translation is as a bridge. The original poem has its place, its home, in its language. All those who know the language have access to the poem, but it is out of reach for all others -- until someone builds a bridge. That bridge must start from the native language of the translator, who undertakes the task to connect the new reader to the original. The better the translation, the more solid the bridge, and the more likely it is to transport new readers back to the source. A poor translation requires much from the reader, much clinging and perseverance, if he wishes to understand the poem, and many will be lost along the way. A fine translation, by contrast, will allow the new readers to pass smoothly as if traveling in their own country, and yet experience something they couldn’t otherwise see. The strongest bridge of all is that which inspires the new reader to try to learn the language itself, so that he can approach the poem in its genuine Essence.

And so, that is my project, however long it takes me -- years certainly, or a lifetime, perhaps. I hope I can build a sturdy bridge for future travelers. All pilgrims are welcome on the road toward Bhit Shah.

a post-script: I intend to append here a specific discussion of one of the brief translations I have already done of a verse from the Shah jo Risalo, with explanations of my specific thinking in making the choices I have made. That should give a little more tangibility to the theoretical ideas I have discussed above. For now, here is a link to a Facebook album in which I have compiled those few verses which represent the beginning of my attempt: "Translations from Shah Latif"

9 Comments

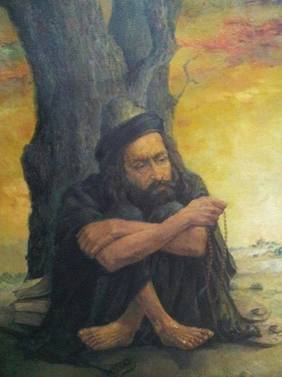

Image at top left is a digital

portrait by Pakistani artist

Imran Zaib, based on one of my own photographic self-portraits in Thari dress.

portrait by Pakistani artist

Imran Zaib, based on one of my own photographic self-portraits in Thari dress.

Author

Curious mind.

Archives

September 2020

March 2018

February 2017

October 2016

June 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

July 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

October 2014

August 2014

April 2014

February 2014

January 2014

RSS Feed

RSS Feed