|

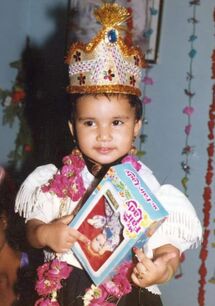

It has been quite a while since I have written an entry to this blog. An immensely sad event has prompted me to return here now. A few days ago, my Sindhi family and our entire circle of acquaintances were shocked by the sudden death of my youngest Sangi sister, Mehak. She died of cardiac arrest on 19 September 2020, following a few months of heart issues that might have been caused or exacerbated by the case of COVID-19 that she contracted earlier in the year. The family had been quietly worrying for her, but no one could have expected such a sudden and tragic outcome. This post is a tribute to a wonderful younger sister, written by the sister who came late into her family, but was nonetheless treated with love from the heart. My sister Mehak was perfectly named, as the word means “fragrance.” Her presence was a gentle one, always calm and pleasing, never brash or bold. What I will always remember first about her is not something concrete, but rather a feeling and a glow that accompanied her presence. She is a difficult subject for writing, because her memory wafts in ideas and colors more than in solid facts or anecdotes. It is often easier to describe her in terms of what she was not; and yet I do not want to give the impression that she was insubstantial as a person. Quite the opposite: she was strong, a person of grit, integrity, deep thought, and compassion. Nonetheless, it is her spirit that seems to me the most vivid aspect of her, and which I hope that these rambling words of mine will evoke in some small measure. In groups, Mehak spoke little, but smiled often. I would not call her shy, however: she had a sense of ease about her, a sense of comfort in her place, which had the effect of putting others at ease. I am sure she put me at ease on countless occasions. Especially early in my time with the Sangis, when I could understand almost no Sindhi, there were many times when conversations would flow around me, leaving me feeling muddled and misplaced. I can’t remember any of the gentle and amusing things that Mehak would tell me in these moments, but how well I can remember the childlike smile that would accompany them, that innocent grin which could instantly lift a sagging mood.  Baby Mehaki Baby Mehaki Mehak was the baby of the brood, the last but most loved of our generation of Sangi children. (I myself, though last to arrive in the Sangi family, am the eldest of the ‘kids,’ being a couple years older than the otherwise-eldest, Marvi). With her especially round cheeks and bright eyes, Mehak fulfilled the role of the baby sister to perfection. Though the Sangi household was already a sunny one, Mehak herself soon came to embody that sunniness. As the other siblings grew older and started to have inclinations away from the home, Mehak seemed to grow deeper into the heart of the home itself. She knew all the ins and outs of the household. She was the one who would make certain that Papa and Ammi took their medicine whenever they were ill. She would pack Papa’s suitcase for any trip he might take, knowing better than he what all he would require away from the house. She anticipated the needs of others and responded with subtle grace. In that special way that youngest siblings sometimes have, she was able to combine her bright youthfulness with unexpected emotional maturity.  Mehak with niece Areej Mehak with niece Areej Though she was the baby of our generation, Mehak was the most excited of all to welcome the babies of the next. I can well remember her immense excitement upon the birth of Marvi’s first daughter, Areej. Mehak had designed a large poster offering in glittering letters: “Welcome Areej Fatima, our precious angel.” Mehak took to Areej, and then to the two nieces who followed soon after, with no less love than if she were their mother. And their love for her was scarcely less intense than for their own mothers. Mehaki’s new name in the home became “Kaka Mehka,” which was Areej’s early version of “Kaala (Aunty) Mehak.” Her presence was a natural balm to young children, and a source of true joy and comfort. Although Mehak was as much of a household angel as could have been desired in olden times, she was also a modern woman of emancipated intellect. She took her medical studies extremely seriously. When her other household duties had been attended to, Mehak was always to be found with a textbook on her lap. I am a bit amazed when I think back: this peaceful person was actually never at rest. She was working, she was caring for others, or she was studying. In all of these, she was giving herself wholly and sincerely.  at her bridal shower at her bridal shower Mehak was tremendously beautiful, and yet not the least vain. Her beauty was of the freshest and most natural kind. Many times I have seen her in the first moments of her day, upon rising from sleep, already in a state of rosy loveliness that most women can’t achieve even after hours at the mirror. And when she was in fact made up and adorned in wedding finery, she was absolutely radiant, as countless photos will attest. And yet she never sought compliments or attention based on her appearance. The photos of which she was most proud are those from her medical school graduation, in which she is enveloped in elaborate academic robes, her face framed by hijab, her warm eyes beaming with soft intelligence. It was her hard work and accomplishment, not her surface, in which she placed value. Closely linked to her hard work was her generosity. I happened to be living in the Sangi home at the same time as Mehak began her ‘house job,’ which I understand to be something like joining the medical rotation staff: a first stage in a doctor’s career. With her very first paycheck, she went out and bought gifts for the whole family, including me. How many of us, upon receiving a paycheck for the first time, would even think to spend it on others? And yet I am sure that this was Mehak’s natural and unquestioned instinct.  receiving Papa's blessing receiving Papa's blessing When a person like this suffers, she tends to draw the suffering inward. Not wishing to make a show of herself, or to cause unpleasantness for others, Mehak would tend to hide any pain, emotional or physical, within herself. She was subject to migraines, one of those most invisible of illnesses, which causes the sufferer such internal agony. She never revealed that pain upon her placid face, but bore it bravely, fading into the background to take rest only when it was absolutely needed. When life events brought her emotional upheaval, very few of her loved ones could know how much she must be suffering inside. It is possible that when she became ill a few months ago, this internal suffering could have aggravated the problem with her heart—but of course there is no way to know what happened with any certainty. What I feel sure of is that Mehak had a deep interior life, rich with emotions of many kinds. Although the keeping-in of pain may have caused her harm, other aspects of her interior life gave her great strength. She was deeply religious, a true believer in Islam, and one of the finest examples of a Muslim that I have known. She prayed regularly, but never made a show of it. She did not lecture others on how to act; instead, she simply acted well herself. She was a model of selflessness, generosity, and kindness.  Mehak with her husband, Ghulam Mujtaba Sangi Mehak with her husband, Ghulam Mujtaba Sangi I last saw my sister Mehak during her wedding celebrations in December 2019. A few nights before the wedding, we held a bridal shower for her in ‘my’ room (which is a great big room at the top of the Sangi house), for which I took photos. The next night we decorated the lawn and ourselves with flowers for her Wanwah celebration, and Mehak was bright and glowing among the marigolds. Our sister Moomal did the makeup for this night and the next, and she told me how special this was for her, because as a little girl Mehak had often requested: “moon khey kunwaar kayo!” (“Make me a bride.”) On the night after the Wanwah, we celebrated the Mehandi (‘henna’), at which the engaged couple receives blessings from the family and then is entertained by dancing from the siblings and cousins. The ceremony opens with all the sisters and female cousins processing in carrying cakes of henna bearing candles. Being the eldest of all, I was given a place at the front and center of the procession, which was an honor I will always cherish. I also led the dandia (stick) dance, which was the last of the evening—and though our performance was not exactly stellar, it is a sweet memory too. It was a delight to see our beautiful Mehaki sitting next to the young gentleman who would be her loving husband, though we now know how brief a time they would be allowed together in this life. After the Mehandi ceremony I had to spend much of the night packing my suitcases, because I had been called back suddenly to the US: my father’s long illness had become suddenly critical, and I was needed to help care for him in his last weeks. As a result I had to miss the actual Nikkah (wedding) ceremony, much to my great regret. Mehak was completely understanding about my need to go home to my father, and we parted with hugs and assurances that there would be many more occasions to celebrate in the future. And I returned to Sindh with the intention of seeing my Sangi family in the middle of March, at that time not knowing how widespread the COVID pandemic would become. That trip was cut extremely short: I spent a few days with friends in Karachi and then left again directly from there, as countries were beginning to close their borders in quarantines. Thus I was not able to see my sister then, and now, not ever again.

At time of posting, it has been seven days since Mehak left us. Our sister Marvi sent me a photo of her grave, strewn with fragrant rose petals. Yet it is impossible for me to grasp that she could be within it. Marvi wrote to me, “she is invisible, but she is all around us.” Mehak is not gone: she is the fragrance of the rose petals. She is the peace that will eventually bless the home once more. In this world we will forever miss her company, yet we will never be without her spirit.

48 Comments

|

Image at top left is a digital

portrait by Pakistani artist Imran Zaib, based on one of my own photographic self-portraits in Thari dress. AuthorCurious mind. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

emily s. hauze

RSS Feed

RSS Feed