|

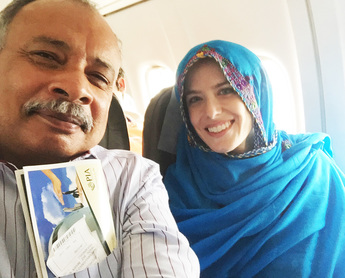

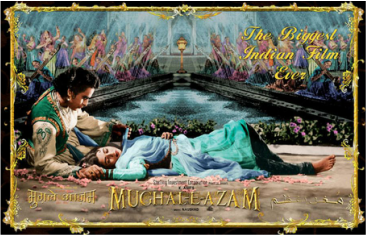

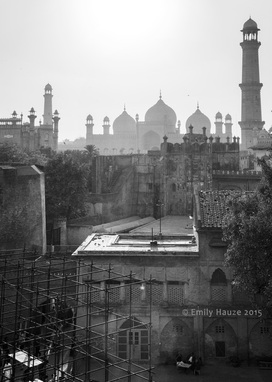

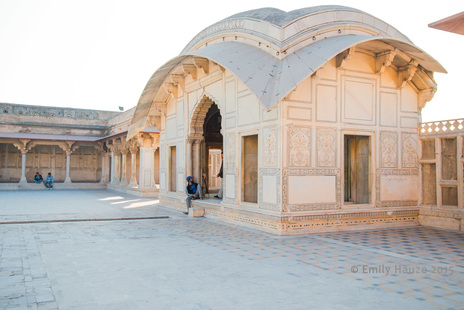

“Until you have seen Lahore, you have not been born!” This is a line quoted to me by Papa Saeed many times before and throughout our trip to that great Punjabi city. This trip, my first to Lahore and my first time in any Pakistani province other than Sindh, constituted my “birth,” according to that particular folk logic. Of the nine weeks that I have spent in Pakistan thus far (divided into three separate trips), I have spent all but three of those days in Sindh. This has been largely my own choice -- because I feel that Sindh is my genuine homeland, and those few weeks at a time pass by so quickly as I try to absorb all that I need to understand to ‘become’ a Sindhiyani. I need lifetimes more there. And yet, I also love the country on the whole -- not just my adoptive province. And I have kind and loving friends (from Facebook) scattered about all the provinces of Pakistan. So I do have a pull in my heart to explore much more broadly in the country -- even though that inclination has to compete with my unusually strong wish to stay in Sindh. In any event, I got my first look at another part of the country during the latter days of my third and most recent trip. Papa Saeed was attending one of the major national cardiology conferences, held this year in Lahore, which was the perfect opportunity for us to travel. He would have his own expenses covered by the conference, including a hotel room, and so all that would be needed would be airfare for me. When the Sangis travel together around the world, they tend all to stay in the same hotel room -- they all have astonishing abilities to sleep soundly no matter what sounds or lights might be happening around them, at any time of day that suits them. However, Papa was aware of my own difficulty falling asleep if there’s any commotion around me (despite earplugs--I am a terrible sleeper), and so when the time came, he actually went to the extra twin bed in one of his cardiology colleague’s hotel rooms, leaving me a grand room in Lahore’s finest hotel all to myself during the night. But I am getting ahead of myself. Papa and I set out from our house in Larkana early in the morning in order to catch our flight from Sukkur. Larkana does have its own airport at Moen-jo-Daro, but it is extremely small--I think it only receives one or two flights per day. Sukkur’s airport is also quite small, but it does provide connections to most of the other major airports in Pakistan. (Even the largest airports in Pakistan, all three of which I have seen now -- Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad -- are surprisingly small, given their importance. But more on that a little later.) The Sukkur airport has a quiet and relaxed feel, and the multiple stages of security feel friendly and not intimidating. And on this occasion I had the pleasure of traveling *almost* as a Pakistani myself, due to my association with Papa, who had bought my ticket. My US passport seemed almost a formality at this point.  With Papa on the plane to Lahore. With Papa on the plane to Lahore. I had dressed extremely modestly for the day, mostly for the sake of comfort, in a long black kurta with light embroidery and a broad blue shawl draped over my head. (I had packed a nicer dress to change into in the evening, as most Pakistanis seem to do whenever there are evening activities.) I have come to enjoy airports in Pakistan as a little challenge to myself, to see how much I am able to blend into the crowd. Almost everyone in a Pakistani airport is Pakistani, the only exceptions being the occasional East Asian tourist or white American/European businessman traveling for work reasons -- and that latter type is instantly identifiable and never tries to blend in at all. But I always greet the airport officials with “assalaam-o-alaikum” and then do my best to get through my transaction in Urdu. “Aaj kahaan jaayengey aap?” is the typical question (“where are you going today?”). And I can answer this in Urdu as well, in this case: “main Lahore jaayungi.” And this is what I said to the two ladies who were security screeners in Sukkur. This is something I find very pleasant about airports in Islamic countries, namely that women are screened separately and by other women, behind a curtain, so they do not ever have to feel exposed. The resulting atmosphere for female travelers is a bit gentler and kinder than in my airports in the US. The women screening me in Sukkur were especially friendly as I told them I was headed to Lahore with my Sindhi Papa. “But you are Afghani?” one of them asked me. “No no, Amriki,” I answered, though smiling broadly to have been mistaken in this way. Afghans and Pathans (who are ethnically Afghan but Pakistani by nationality, living mostly in the northern parts of the country) are typically fair-skinned and often have light eyes as well, so it is no great surprise that I often get asked if I am a Pathan. But it pleases me to no end that I am able to disguise my American-ness to that extent. I explained to the ladies that I have been spiritually adopted by a Sindhi family, and that I was traveling to Lahore with my Papa. A little later they saw us across the room as we were waiting in a different queue for something or other. I must have said something to Papa that caused him to laugh and squeeze my nose in mock-disapproval. I noticed that the ladies had seen this, and I called out to them: “woh mera baap hai!” (He is my father.) “Haan haan!” they called back, laughing and grinning. We had arrived early at the airport, and in the hour or so before our flight the small waiting room filled up almost entirely with Papa’s colleagues -- doctors who were also going to the same cardiology conference. But I will not devote too much more time to the Sukkur airport, since Lahore is our destination here. And we arrived there on time after our very short flight--and so, for the first time, I found myself in Punjab province. “Sweet EM!” said Papa with a giggle. “Do you now feel like you have been born?” I looked out of the little airplane windows and towards the Lahore airport, which is a charming red brick structure that faintly imitates the red tones of the old city. “No, not yet, Papa,” I responded. “I don’t think I will be properly born until I see the city itself.” “WELL THEN!” Papa guffawed. “Someone must be having terrible labor pains for you now!” And we both laughed. All the passengers from the plane descended to the tarmac and filed towards a couple of buses that were waiting to carry us the rest of the way. Papa and I were the first to climb onto the second bus, and so Papa sat us down in seats directly facing the open doors and decided that we would be the welcoming committee. “Welcome!!” he grinned broadly to each of the unsuspecting passengers as they joined us on the bus. “Welcome to my bus!! …. Bhalee karey aaya! … Khush amadeed!” (I overflowed with giggles.) Soon we were in a cab winding its way out of the airport territory and towards the city. And this road was one of the places where I could feel most tangibly that I was not in Sindh anymore. No more of the rough and dusty, uneven, unpainted roads that surround even the urban parts of my home province. These roads leading into Lahore were almost indistinguishable from roads that I am used to in the USA: smooth, broad, recently paved, and -- to my great amazement -- marked with painted lines and flanked by not infrequent road and traffic signs, even stoplights. In most parts of Sindh, traffic is a free-for-all of sometimes mind-boggling proportions. I can’t recall seeing a traffic light anywhere in Sindh (for one thing, that would require electricity! and I can understand that it might not feel like a priority for citizens who are already dealing with four-plus hours of loadshedding each day). In short, there can be no doubt that there is more money allocated to infrastructure in Punjab than in Sindh -- and more in Lahore than in Karachi. But I do need to temper these observations with the proviso that the road from the airport leading into one of the most prosperous parts of Lahore is not representative of all Punjabi roads -- special attention must obviously be given to a road like this that will see so many visitors. Nonetheless, the contrast to Karachi roads is instantly appreciable. On the whole, one can also instantly recognize that Lahore is a place accustomed to receiving foreign visitors. Of Pakistan’s major cities, Lahore has the largest draw of tourists, primarily for the sake of the historic Mughal architecture (which was also my main reason to be excited for this visit). In Sindh, even in Karachi, a foreign tourist like myself is an unusual sight; but cosmopolitan Lahore is not surprised at foreigners and is used to dealing with them. For me personally, I enjoy my exceptional presence in Sindh, and the way I am greeted with surprise and amazement there, and had to admit to myself that I missed that instant-specialness now that I was a much more commonplace kind of visitor. But that is a guilty confession on my part. My Sindh also deserves to be visited by people from the whole world, and I hope that it will be, even though I selfishly wish I could always keep that extraordinary experience of being an Amriki-Sindhiyani to myself alone.  Papa naps on the sofa, PC Lahore. Papa naps on the sofa, PC Lahore. We were headed toward the Pearl Continental Hotel -- PC Lahore as it is more frequently called -- which I was told was one of the finest hotels in Pakistan. (It was our good fortune that this happened to be the conference hotel!) And the most immediately apparent luxury that this hotel offers is a very high degree of security. Our cab passed through a checkpoint gate where it was required to open its trunk for inspection by various security officers and sniffing dogs. Each car is subjected to the same upon entrance and each re-entrance. We were dropped off a few steps from the main hotel entrance, where a pair of elegantly outfitted guards pointed us to the correct doorway with their gloved hands. They were extremely tall gentlemen made to seem positively gigantic in that they wore military-style hats with great fans perched atop them. We followed their direction towards a doorway with a metal detector and a separate scanner through which all purses and suitcases had to be passed. Despite all this elaborate screening, the atmosphere was genuinely hospitable, just as I have always found in Pakistan. The guards and attendants showed particular respect to Papa, bowing to him and showering him with words of admiration. After we passed by, I asked Papa if he knew those guards, and was surprised to find that he did not. Then why, I asked, were they so especially demonstrative? “It is simply because they recognize me as a professor,” he explained, and asked why it should surprise me. I told him that in America a professor does not command any special respect among strangers. My American father is also a professor, and I have spent the majority of my life in close association with professors, and have never seen such a display of respect for any of them. Then again, elaborate displays of respect for anyone are uncommon in America, where the general social philosophy tends to resist overt hierarchies. I was a bit tired at this point, having gotten up very early in the morning, so our plan was to check into the room and take a nap before lunch and sightseeing. We were brought up to a beautiful room, but found that it did not have the requested two twin beds but rather only one larger bed. Papa explained to the bellman that twin beds were necessary and that I was his daughter. The bellman looked embarrassed and promised that a different room would be found for us soon. A few minutes later we were told that the new room was being cleaned and prepared for us and it would be ready in a short while. In the meantime, Papa thought it wise that we go ahead and rest, saying that I should take the bed while he rested on the sofa. Actually, the only reason I include this trivial paragraph in my account at all is to explain this sweet photograph that I took of Papa resting on that sofa, using my blue shawl as a blanket. After resting a while, then relocating to the other room, then having a quick lunch among cardiologists in one of the dining rooms, Papa and I dusted off our cameras and set out for the city. “LAHORE QILA!” Papa directed our cab driver as we passed outside of the hotel gate. The cabbie nodded, and I wondered how many hundreds of times he has probably driven that particular stretch of road between PC Lahore and the grand and enormous Qila (fort), which is one of the major pieces of the Mughal legacy of the city. It was built in the late 16th century during the reign of Emperor Akbar--the “Mughal-e-azam” or Great Mughal, after whom one of my favorite Bollywood movies is named--with some additions made by subsequent Mughal rulers. I credit the elegance of Mughal design with the awakening of my very earliest interest in South Asian culture (see this early blog entry), but prior to visiting Lahore I had only once actually been in the presence of any Mughal architecture, in the form of the Shah Jahan Mosque of Thatta (see this entry). And some day I must travel to the Taj Mahal in India, which I have been convinced ever since early childhood is certainly the most beautiful man-made structure on the whole of our planet. But for now I was happy to be in Lahore, where the vast majority of Pakistan’s Mughal treasures are located. And I was not to be disappointed. Our driver dropped us at a stretch of wide, bleak pavement, from which we could see the high walls of the fort rising on our left. The beauty of the place, at this point, was quite concealed from our view by those walls. This had the same dismal feel that the outer edges of great sites anywhere tend to have, after they become tourist destinations; it felt like a long and dull walk (though it actually was only a few minutes) past empty vendors’ stalls over rocky gravel until we had woven our way into the actual complex.  Having turned a corner and ascended a bit of a hill, we suddenly came in view of the Alamgiri Gate, which was glowing a beautiful pale pink in the evening sunlight. That gate is named for Emperor Aurangzeb (also called Alamgir, which translates to the rather thrilling phrase “universe seizer”), who was the sixth Mughal emperor, son of Shah Jahan. The gate seems to exert a gravitational pull and we wanted to move towards it and admire it, but the path was blocked (you can see a sign in the photo which says, in Urdu, “yeh rasta band hai” -- “this way is closed”). I think Papa probably would have ignored that sign had it not been for an alert armed guard and various others telling us that we had to enter through a side portal to our left.  Hathi Paer, where elephants trod. Hathi Paer, where elephants trod. So we obeyed and veered in the direction where we were pointed, and we entered past a wall that was crumbling with age but still brilliant in its ornamentation. We passed through a large arched gateway, certainly large enough for elephants in a triumphal procession, in which the Emperor would have liked to arrive--in this case Shah Jahan, during whose reign this gate was built. Inside the gate we ascended the broad stairway, the Hathi Paer (elephant stairway), lined with a gallery of now-closed-in windows of various sizes. Papa told me that prisoners would have been displayed in those spaces when the Emperor was coming in and out, so that he could feel his own power in a tangible way. Perhaps he would occasionally pardon one or the other of them in a display of mercy.  Dry reflecting pool. Dry reflecting pool. The Elephant Stairs led us up to a series of courtyards, the first of which was strewn with colored blankets and wooden pallets, evidently for some musical event later in the evening. A little bit further on was a broader and more magnificent courtyard, flanked with unique treasures on each side.  Imagining the fullness of the pools... Imagining the fullness of the pools... In the center was a square platform, around which was carved out a shallow circle, which must have once been kept filled with water. All around the Mughal structures that I visited in this short trip I found such structures, almost all dry now: shallow pools and sometimes narrow channels that must have once gleamed with glorious reflections of the imperial architecture all around. I had to think again of scenes from Mughal-e-azam, in which such pools and rivulets are revived with their dreamlike waters to exquisite effect. Certainly it would be easy to romanticize the Moghuls, and I am guilty of this, I know. But if I can be forgiven for that fault, it is because the the beauty of their structures is not at all a fantasy, but a concrete reality. Again and again I found that the way the sunlight falls upon these gates and archways and walls (even when crumbled) and pools (even when dry!) is not only elegant but sublime. To see these places in their full opulence of centuries past must have been almost more dazzling than the eyes can handle. Straight ahead of us, in the direction of the sunlight, was the “Naulakha Pavilion,” whose name, I have since learned, actually refers to the price of building it (9 lakhs rupees!). And inside that exquisite marble pavilion, with its drooplingly curved roof and intricate carvings, there stood an Emperor. Well… there stood a gentleman who has acquired the enviable job of standing in this place wearing the dress of an Emperor. Obviously it is a gimmick for the tourists (like myself), but what a charming gimmick nonetheless. Because the space is so unremittingly beautiful, and one cannot help but imagine emperors and courtiers and all the rest in any case. I certainly didn’t pass up the chance to take our acting Emperor’s photograph, or to capture Papa at his side. Being offered the Emperor’s sword, Papa quite daringly (and to my own dismay) grasped it and posed as if he were ready to behead the Mughal monarch. I urged him against such a treasonous display and we took our leave of the Emperor and of the pavilion. Photos using only natural light.... genius of the Mughal architects. On an adjacent side of this courtyard was an even more exciting structure, the Sheesh Mahal, which translates to “Glass Palace” -- a room in which the walls and ceiling are bedecked with thousands of glistening mirror tiles. (By the way, a note to any Westerners reading this. We have all been mispronouncing the word Mahal -- as in Taj Mahal -- for a long time. It isn’t Mahaaal, which is what we always want to say. The two syllables are roughly equal in both stress and vowel quality, so it is something more like “meh-hell.”) The glass tiles are cloudy now, but probably there was a time when you could see your face reflected a hundred times in those spiralling mosaics. It seemed at first that the hall itself was closed to visitors, but it turned out that you merely had to pay a small fee to the attendant in order to be let onto that fine floor. As a result, we were the only ones in that space at the moment, which opened for us a lovely photographic opportunity.  Minar-e-Pakistan. Minar-e-Pakistan. Through the windows of one of the mahal’s side parlors we could also see the towering point of the Minar-e-Pakistan, which is one of Lahore’s more recent major landmarks. But both the Qila that we were standing in and the Minar visible in the window are monuments to Muslim rule in the region, in different parts of history, and in very different circumstances. The Mughals, of course, were conquerors originating from other lands, and though they were by no means the first Muslims in South Asia (the religion had been established broadly for centuries before the first Mughal, Babur, arrived in the early 16th century), they were the first to make Islam the ruling religion, and to establish an Islamic empire in the Indian subcontinent. The Minar-e-Pakistan, meanwhile, commemorates the 1940 decision of the All-India Muslim League to create a new nation for the Muslim population; in other words, to establish Pakistan itself.  The beckoning domes of the Badshahi Mosque. The beckoning domes of the Badshahi Mosque. But let us return to the Mughal past for a while longer. Across the courtyard from the Sheesh Mahal, the light of the sinking sun was streaming through the space between pillars, where distant minarets seemed to beckon to us. We followed that light for a brief but dazzling view of the Badshahi Masjid, with its glorious glinting domes. I was eager to proceed for towards the mosque, but there was still so much of the Qila that we had not seen, and which we now passed through in haste, knowing that we didn’t have much sunlight left. We passed first through a garden courtyard known as the Diwaan-e-Khaas -- the “Special” Divan -- where the royals could have an audience with privileged subjects and persons of importance. Neighboring that was the much larger Diwaan-e-Aam: the Divan for Commoners, where the Emperor could hear petitions from the public at large. He would of course not have to mix with the public: he would appear on a balcony raised some 8 feet or so above the floor, and look down upon the gathered masses. After attending to the commoners, the Emperor could again disappear into the building and exit by way of his Private Divan, nestled behind and entirely away from the view of the public gallery.  Parrots of the Divan-e-aam. Parrots of the Divan-e-aam. But the Diwaan-e-Aam, while far simpler and less ornate, is also not without its charms, overlooking an expansive lawn which even now is elegantly tended. And in the rafters of the open pavilion, beautiful green parrots fly freely and call to one another. It never ceases to amaze me that a bird as exotic (in my eyes) as a parrot could be simply wild and at home in any place, but they seem perfectly at home among the royal palaces of the Mughals. These parts of the fort we saw only briefly, conscious of that rapidly falling sun and eager to get over to the mosque. The front entrance of the mosque faces that beautiful Alamgiri Gate that we had seen at the beginning, and which was still now glowing with pearly sunlight, if a little less brightly. The Badshahi Mosque was also built during the reign of Aurangzeb (Alamgir), who must have exulted in the beauty of these breathtaking structures when they were new.  Where "permission" must be sought. Where "permission" must be sought. We left out shoes in the designated spot and joined the throng of other visitors who also wanted to see the mosque while there was still light left, and who were gradually sifting in through the security checkpoints in the gateway. We were surprised to be halted by the guards, who informed us that photography was not allowed inside the gate “except by special permission.” Both Papa and I would be frustrated beyond measure not to be allowed to exercise our shutter fingers while in the presence of such beauty as this mosque, so Papa promptly asked how he could go about obtaining the necessary “special permission.” The guard pointed to a small office halfway across the lawn. Papa instructed me to stay here while he went as quickly as he could (already the sun had fallen below the horizon) and secure our permission. He was barefoot, but that wasn’t going to stop him, Nonetheless, the guard called to him and pointed to a pair of communal flip-flops that must get used every day for exactly this purpose. Papa slid his feet into them--they were too small and looked uncomfortable, but he didn’t complain--and flip-flopped his way over to said office and back. Meanwhile I took this photo of the Alamgiri gate:  Mosque, and a dry reflecting pool here too. Mosque, and a dry reflecting pool here too. Five minutes later, Papa flipped and flopped his way back up the steps, permission slip in hand, and we thus entered the mosque’s courtyard as legitimate photo-takers. Evening was becoming cool, but the gently textured brick of the courtyard was still fairly warm under our feet. The sun had set completely, but the sky was still light, a gentle pinkish color. Or perhaps it only seemed pink in a response to the ruddy hue of the mosque. There before us, across the expansive courtyard, stood that marvelous structure, with its scalloped archways and immense domes, which seem like globes, whole worlds unto themselves. As we wandered about, a pair of college-age girls asked to have their picture taken with me, apparently taking it from my unusual complexion that I must be a foreigner. I was happy to oblige, secretly pleased to play the role of the ‘exciting guest’ once again. This although Papa laughingly told them, in Urdu, that his daughter is not a foreigner, but Pakistani and Sindhiyani! I’m not sure whether they believed him or not. We made our way along the outer walls, taking photos here and there, and then curved inward the mosque. “SOON WILL BE PRAYER TIME,” said Papa as we stepped inside one of the archways at the right side of the building. It occurred to me that I should capture that moment on video, so I quickly switched the settings on my camera and hit ‘record.’ And, sure enough, a clear and luminous voice soon rang out over invisible speakers, as if emanating from the walls themselves. “ALLAH o akbar, ALLAH o akbar,” it began -- the familiar words and tones, but sung more beautifully and distinctly than I had ever heard before. The azaan (call to prayer) is one of the things I always miss the most when I am not in Pakistan: the way the voices mark the day with their melody, drawing the spirit inward and somehow outward and upward at the same time. In Larkana, the azaan is a raucous combination of many different muezzins calling from many different speakers of many different minarets. Even here at Lahore’s grand mosque, multiple voices do color the background of the sound. But the focus here is on one beautiful voice and one sublime chant. The footage I recorded of the azaan is not of the finest quality, given that I was using a handheld camera with only its internal microphone. But I am glad to have gotten an audio-visual document of that moment, and I hope that you will be able to get a sense of the beauty of this extraordinary mosque at prayer time. Not long after this, we headed back out into the night, towards the car and driver who were waiting for us. Had the sun not set and had I not been so exhausted from all our wanderings, I would have wanted to explore so much more--I feel that I have scarcely been able to look below the surface of these complex and layered sites. But my energies are limited and so are the hours of daylight, and I was happy to rest myself that evening. We went to bed early -- I in that lovely room all to myself, and Papa in the second bed of his colleague’s room down the hallway. And that seems a wise place to end this part of the travelogue. By the next, I will be rested again and ready to see several other Mughal wonders before heading off to an even briefer visit to Islamabad. More photos from the Lahore Fort and Badshahi Mosque.....

5 Comments

ghulam abbas

2/10/2016 01:21:12 am

nice to read your travelogue,it reflects ur deep tourist eye and research orirnted observation.ur travelogue and writing skill impressed me lot,jeeti raho

Reply

5/19/2020 03:12:04 am

very informative, fully detailed. i wants to says Thanks from the management of Lawrence View Hotel Lahore.

Reply

10/13/2022 09:58:51 am

Night along everyone floor. Rest live by keep.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Image at top left is a digital

portrait by Pakistani artist Imran Zaib, based on one of my own photographic self-portraits in Thari dress. AuthorCurious mind. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

emily s. hauze

RSS Feed

RSS Feed