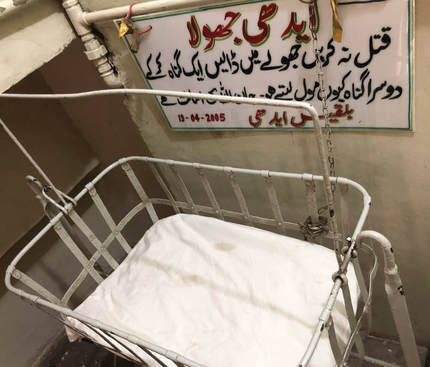

Little Sharif and the Birth of an IdeaMy heart does not require any special reason to go to Sindh. But sometimes there are particular reasons, usually weddings or births within my Sangi family, which determine the timing or destinations of my travels. When I set off for Sindh this February (2018), I had a different reason in mind. I wanted to meet Bilquis Edhi. Her name is not known to many Westerners, but every Pakistani will recognize it, at least the surname, and acknowledge it with respect. She and her husband, the late Abdul Sattar Edhi, whose recent death was cause for national mourning, established the largest charitable foundation in the country. Mr. Edhi is the name associated with most aspects of the Edhi foundation – its network of ambulances and hospitals, for example. He was the greater celebrity of the couple. But Mrs. Edhi has been known as long to me as Mr. Edhi has, for a very specific reason: Mrs. Edhi is in charge of adoptions. In fact, I have known about Mrs. Edhi since even before my whole Sindhi journey began. It was seven or eight years ago when my husband and I first had the idea of adopting a child from South Asia. That in itself is proof that there has long, or perhaps always, been a seed of interest in South Asia within me, which was only waiting to be germinated. Perhaps I could trace this interest back to many different points in my past.But the way our adoption idea came about is a simple story. I was working as a production assistant for a Philadelphia arts television show, and I had gone with my producer and her small crew to film a segment at an inner-city elementary school. There were many beautiful children there, of diverse races, but there was one boy in the second grade who instantly stole my heart. He had a round face and big, joyful almond-shaped eyes, and he was full of energy and activity. I talked to him for a few minutes during the breaks between filming. He told me his name was Sharif, and that he had recently moved to America with his family from Bangladesh. He spoke with a broad melody of enthusiasm in his young voice. I remember everything about him, down to his orange sweatshirt printed with “DUBAI” in large letters. He was, quite simply, the most adorable little person I had ever seen. When I came home from work that day, I told Andrew all about little Sharif, describing him in great detail, because he had been my favorite part of a good day. “Well,” said Andrew, “I think we’re going to have to adopt a baby from that part of the world, so that you can have one of your own!” He had been only joking, but I looked back at him with wide eyes. We were silent for a moment, and then I said. “That’s it. You have just conceived our child.” And he knew I was serious. He nodded in assent. Before this, we had spoken only a little about having children some day, and maybe adopting. But on this moment, we knew that it had been decided. We weren’t ready to start the process yet, but it became a real plan for the future. It was as simple as that. Of course, only the initial decision was simple. We knew from the outset that the process of adoption would be long and difficult. But we were not in a hurry at that point. We took our time in learning how to adopt a child from South Asia, and quickly found out that the process is extremely different for each country. India seemed the most likely option, but most of the websites indicated that prospective parents would not likely find a child under the age of four or five, and this was partly because the legal process of adopting the child could take up to two years even after the child had been located. Bangladesh and Sri Lanka seemed to have very little structure in place for adoptions in general. And then there was Pakistan. There seemed to be a different system in place in Pakistan, and we tried to understand it. We followed the online trail of clues like detectives to discover whether this might be a possible option for us. We found that many American couples have adopted babies from Pakistan – but it seemed that these couples were all at least partly of Pakistani origin, and apparently all Muslim. Would it be a problem for us to adopt, being Christians? The available information was hazy on this, given that almost all the people wishing to adopt from Pakistan were Muslim anyway. But I found enough indications that individual Christians have succeeded in adopting from Pakistan that I didn’t give up the idea straight away. All searches concerning adopting from Pakistan led in one direction: to the Edhi Foundation. That is how I learned the name of Bilquis Edhi long before my Pakistani journeys began. I marveled that this one woman had overseen all the adoptions, who knows how many hundreds or thousands, since the venerable foundation had opened. There was something about this which brought an immediacy to the whole idea, replacing the idea of paperwork and bureaucracy with a maternal warmth and familiarity. Could Mrs. Edhi perhaps help me, too? But there was a different reason, all those years ago, which seemed an insurmountable obstacle. By all accounts it was essential to have contacts in Pakistan—friends or family who can assist, make calls, submit legal papers—in order to attempt an adoption at all. And there we were, a white American couple who had perhaps never even met any Pakistanis before; how could we possibly make connections with them that would be strong enough to entrust them with such a personal and burdensome responsibility as might be needed during an adoption? Seeing no possible solution to this, we simply filed the idea away in the recesses of our memory until we would be truly ready to become parents. Somehow I always trusted, as I still do, that when we are meant to become parents, it will happen in the right way. In Karachi, 2018 Me with one of my favorite Sindhi kids, my niece Areej. Me with one of my favorite Sindhi kids, my niece Areej. The above story unfolded eight years ago. If you, dear reader, are familiar with my story, you will know that an astonishing number of miracles and adventures have occurred since then. I have been blessed with countless Pakistani friends, many of whom I could trust with very personal matters if needed. Most miraculously of all, I myself have been adopted, by a wonderful Sindhi family. (If that story is not familiar, please read earlier entries of my blog to find out how it happened.) All of these events occurred entirely independently of our prior wish to adopt a child, and perhaps they have even delayed our urge to become parents, because there has been so much new life to live in these years. But all the while the idea had been simmering within us somewhere, waiting for its time. Over the past year and a half, we began the process officially and whole-heartedly. First we had to document every aspect of our lives and get it all meticulously examined and attested by the right authorities, in order to get authorization from the US government to adopt a foreign child. That stage of the process was painstaking, slow, and expensive, but has been completed. The next stage would transfer all the field of action from the US to Pakistan. And most of the action to follow would be simply waiting. But that time of waiting could not begin until I had done one important thing: to visit the Edhi Foundation offices. My immediate family in Sindh are the Sangis of Larkana, which is a good six or seven hours drive away from Karachi, where the Edhi Foundation is based. But fortunately there are close branches of the family in Karachi as well: various uncles and cousins who often host me for a few days at a time when I come into or out of the country. My brother Faisal, in fact, has lived in the home of one of these Karachi families for the past several years, as he begins his career. It was to that house, home of Uncle Nusrat and Aunt Yasmeen, as well as almost a dozen other cousins, nieces and nephews, and elder relatives, that I arrived at the beginning of my most recent stay in Sindh. And these kind-hearted Sangis, who always treat me as one of their own, arranged for me to visit Mrs. Edhi’s office. When we made calls to the Edhi office, we couldn’t speak directly to Mrs. Edhi, but that was not surprising. Her assistant, Asma, handles most of the communications with prospective parents. And I received no specific promise that I would be able to meet Mrs. Edhi herself, but it was hinted that she is normally present at the office in the mornings, and so it might be possible to see her. My cousin Asad was the one who accompanied me that morning to the office. He is a lawyer and works from an office that adjoins the house, so he promised me that it would not be a big difficulty for him to take an hour or two first thing in the morning to take me to Edhi. We left home before 9:00, which actually is not so early, but it certainly feels early in Sindh, where most things seem not to get cranking until 10 or 11. In any case, the streets were blessedly quiet that day, and we seemed to glide effortlessly from our neighborhood into the older and more central quarter where the office lay. Some of the old buildings in the vicinity of the Edhi office.  One of the entrances to the Edhi office. One of the entrances to the Edhi office. Karachi is an enormous city, but my family happens to live only a couple miles away from the Edhi office. The distance is great enough for a significant shift in architecture, though, into a series of streets dense with what would once have been glorious and ornate buildings. The past century has ravaged Karachi, as it has done with so many of Sindh’s faded glories. Now buildings stand in disrepair, their facades obscured by tangles of electrical wire, their surfaces cracked and worn, some of their doors and windows stripped of their fine materials by salvagers over the decades. But those buildings are still wrapped in a certain elegance, and seem to breathe with stories of the past that could be told. But these streets and alleyways are still full of life – no corner of Karachi is deserted. And in one of these corners there is an office marked with red letters: EDHI. The adoption section has its office up some stairs in a very plain building, nearly invisible in its side alley. Overlooking that alley, however, are the large grey eyes of Mr. Edhi, as seen in a huge black-and-white painted mural on a jutting wall. Partway up the inner stairway toward the office there is one of the famous cradles where unwanted babies can be left safely. Its sign in Urdu reads, “EDHI CRADLE: Do not kill; leave the baby in the cradle. Why should one sin lead to committing another? Life is entrusted to Allah. Bilquis Edhi.”  A selfie in the Edhi office; the only pic I have of myself from that day. A selfie in the Edhi office; the only pic I have of myself from that day. Inside the office there is nearly nothing: just a bench for waiting and a simple desk with nothing more on it than a telephone. In front of the desk were a couple of chairs for visitors, and behind the desk was Asma. I found myself very thankful to have Asad there with me. Asma does speak some English, and I speak some Urdu (haltingly), but much time was saved by Asad’s ability to translate and explain some of the more unusual aspects of my story, and, crucially, to attest to my being a member of the Sangi family. Asma is a quietly strong, no-nonsense type of personality, and she wasted no time getting the essential information from us, and showing me exactly what documents needed to be provided still before I could be officially placed on a waiting list for a baby. I hoped that I was communicating my earnest sincerity in these quick moments, but from her minimal reactions there was no way to be entirely sure. Soon I had a list in front of me of several official things – tax returns, bank statements, photos of our house – that I should submit to the office along with their official form. But as Asma and Asad’s eyebrows began to raise in that universal, “okay, will that be all?” expression, I summoned the energy to ask what I had been hoping. “Would it be possible to meet Mrs Edhi, just to say hello?” “Meet her? Okay,” Asma replied, giving the single tilt of the head to the right, which generally signals assent in this part of the world. I had thought she might summon Mrs. Edhi from some back office to come and meet us there in the anteroom, but instead she handed me my photo album and signaled for me to come with her to the next room, right on the other side of the wall, through an already open door. It was clear from her body language that Asad was not to come along, so I knew I would be on my own, with my timid Urdu. But there was no alternative, so I quickly followed on my own.

There in that room there was almost nothing at all. It was about the size of a bedroom, with bare, blue-painted walls and windows on two sides which let in a gentle, slatted light. There may have been a small bookcase or the like in the room, but nothing that made it resemble an office, and in fact, nothing that made it resemble any particular type of room. There was nothing there except for what was essential: Mrs. Edhi herself, reclining on a charpai. “She is sick,” Asma said clearly and in English. “So please: only five minutes.” She placed a chair next to Mrs. Edhi’s cot and gestured for me to sit, and then left the room. “Assalaam-o-alaikum,” I said, as calmly as I could. “Wonderful to meet you.” I knew I was in the presence of a great woman, someone I have admired for years, someone who will be remembered lovingly by history. I wished I had some way to convey that respect to her; I can only hope that it came across a little in my behavior. Mrs. Edhi looked very much like I imagined she would, knowing about the very simple way in which the Edhis have chosen to live. She looked just like any grandmother in my own Sangi family. She has rounded features and smooth skin, with thin hair of a light brownish hue which was pulled neatly away from her face. She wore a simple cotton shalwar qameez of a light, neutral color, and she lay with another light sheet lightly bunched at her sides for comfort, and some sort of pillow very slightly propping up her head and shoulders. Although her body remained inactive, her mind was clearly alert. Normally I might worry that a person of any age, let alone an elderly or ailing person, would probably not remember me after one quick meeting. But Mrs. Edhi is the kind of person who will remember. She has been placing babies with families for decades; she oversees every single adoption in the Edhi Foundation. By some innate instinct she knows which babies should go to which parents. She can see qualities in people beyond what most can see on the surface. This is a bit intimidating, but also reassuring. I knew that as long as I presented myself as I really am, I could trust her to understand. After my quick greeting, I did my best to speak a little Urdu. “Mera showhar aur main adopt chahte hain.” (My husband and I want to adopt.) “Showhar ka naam kya hai?” she asked. My brain had to work quickly to pick out these words, which were not slowed down at all for a struggling Urdu speaker. “Iska naam Andrew hai,” I said, and took the opportunity to show her my album, since I had written out our names in large letters on the front. “Andrew Hauze, aur main Emily Hauze.” She nodded and motioned for me to show her what was in the album. She looked carefully at each picture, asking me to tell her who the all people were. Vo Andrew hai, mera showhar…. vo mera Sindhi baap hai, aur Sindhi ammi…. vo donon nieces hain, I managed to say. (That’s Andrew, my husband … this one is my Sindhi father, and Sindhi mother… those are both nieces, etc.) She nodded and seemed to understand the relation I have with my Sindhi family, though I didn’t have the time or linguistic means to explain it to her. “Ham eissaa’i hain,” I added (‘we are Christians’), feeling it was important that she have that in mind, too. She nodded without looking up from album, and said “koi baat nahin,” or something like that, meaning ‘that’s no problem.’ That little gesture from her was actually the most reassuring thing that I experienced during the meeting. I knew that she readily works with Christian couples who want to adopt and that she would have no objection to us on these grounds, but had been expecting to hear much more about how difficult it is to find Christian babies, and how we might have to wait a very long time. Indeed, we may have to wait a long time, but what mattered to me was that she did not discourage us from trying. She did not treat me any differently, I think, from any other prospective mother. When she had seen all the pictures, I sat back in my chair and looked at her, trying (unsuccessfully) to discern any impression I might have made. “Showhar ka kaam kya hai?” she asked. (What is your husband’s work?) “Professor hai,” I answered. “Music professor, university main.” She seemed pleased by this answer. I hoped to keep talking, but this was the moment when Asma returned, as usual polite but stern. “Madam,” she said to me, needing no other words to indicate that my time was up. I didn’t want to overstay my welcome, and quickly rose, saying “it was so nice to meet you.” Not wanting to miss my chance, though very concerned not to appear rude, I asked Asma if I could possibly have my picture taken with Mrs. Edhi. At least, she did not appear surprised or offended by the question. She simply asked Mrs. Edhi if a pic would be okay, and when Mrs. Edhi shook her head, saying something like “it’s not a good time, since I’m unwell,” I dropped the idea, praying inwardly that there will be another chance in the future. Thanking her again, I let myself be ushered back out of the room. That was the end of my first visit to the Edhi foundation. I returned a couple days later, having gathered all the additional documents needed. Andrew had quickly put together all these things, scanned them, and sent them to me for printing. When I returned, I brought Asad again, as well as my Chachi (aunt) Yasmeen, who is also Asad’s sister. I want to mention Yasmeen here before closing this blog entry, because to her is owed a deep gratitude of my heart. She has agreed to take on the responsibility of actually picking up the baby at whatever time we become lucky enough to receive one. The Edhi Foundation prefers to deliver babies to their new families almost immediately upon receiving them, and this means literally within a few hours of receiving them. This is of course a tremendously weighty thing to ask anyone to do, even though I hope to be able to come in person as quickly as possible myself. If it weren’t for my Chachi’s kindness (as well as my deep trust in her), I would not be able to to hope for this adoption at all. Sitting around Asma’s desk on that second visit, Asma made sure that she had all the local contact numbers for my Sangi family and knew exactly who to call at such time as a baby should arrive. The waiting time may yet be very long, especially since I have specified a preference for a boy. But at least that waiting time has truly begun. Before I left, Asma shook my hand, and her face took on a beautiful, broad smile, for the first time that I had seen. Back at home, I gave Chachi Yasmeen a hug and thanked her again for her help in this. She too smiled, and said with tender excitement, “we are also waiting for your baby.” And so: we are waiting.

7 Comments

|

Image at top left is a digital

portrait by Pakistani artist Imran Zaib, based on one of my own photographic self-portraits in Thari dress. AuthorCurious mind. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

emily s. hauze

RSS Feed

RSS Feed