|

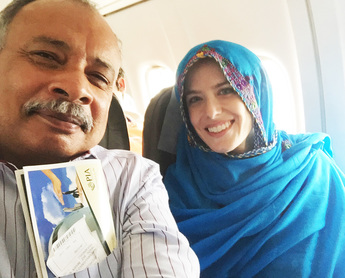

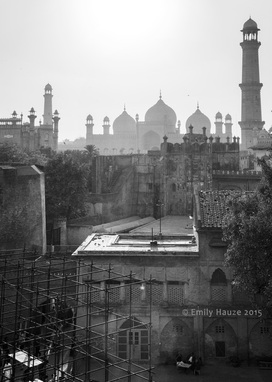

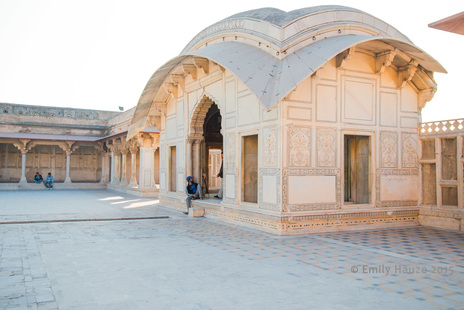

“Until you have seen Lahore, you have not been born!” This is a line quoted to me by Papa Saeed many times before and throughout our trip to that great Punjabi city. This trip, my first to Lahore and my first time in any Pakistani province other than Sindh, constituted my “birth,” according to that particular folk logic. Of the nine weeks that I have spent in Pakistan thus far (divided into three separate trips), I have spent all but three of those days in Sindh. This has been largely my own choice -- because I feel that Sindh is my genuine homeland, and those few weeks at a time pass by so quickly as I try to absorb all that I need to understand to ‘become’ a Sindhiyani. I need lifetimes more there. And yet, I also love the country on the whole -- not just my adoptive province. And I have kind and loving friends (from Facebook) scattered about all the provinces of Pakistan. So I do have a pull in my heart to explore much more broadly in the country -- even though that inclination has to compete with my unusually strong wish to stay in Sindh. In any event, I got my first look at another part of the country during the latter days of my third and most recent trip. Papa Saeed was attending one of the major national cardiology conferences, held this year in Lahore, which was the perfect opportunity for us to travel. He would have his own expenses covered by the conference, including a hotel room, and so all that would be needed would be airfare for me. When the Sangis travel together around the world, they tend all to stay in the same hotel room -- they all have astonishing abilities to sleep soundly no matter what sounds or lights might be happening around them, at any time of day that suits them. However, Papa was aware of my own difficulty falling asleep if there’s any commotion around me (despite earplugs--I am a terrible sleeper), and so when the time came, he actually went to the extra twin bed in one of his cardiology colleague’s hotel rooms, leaving me a grand room in Lahore’s finest hotel all to myself during the night. But I am getting ahead of myself. Papa and I set out from our house in Larkana early in the morning in order to catch our flight from Sukkur. Larkana does have its own airport at Moen-jo-Daro, but it is extremely small--I think it only receives one or two flights per day. Sukkur’s airport is also quite small, but it does provide connections to most of the other major airports in Pakistan. (Even the largest airports in Pakistan, all three of which I have seen now -- Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad -- are surprisingly small, given their importance. But more on that a little later.) The Sukkur airport has a quiet and relaxed feel, and the multiple stages of security feel friendly and not intimidating. And on this occasion I had the pleasure of traveling *almost* as a Pakistani myself, due to my association with Papa, who had bought my ticket. My US passport seemed almost a formality at this point.  With Papa on the plane to Lahore. With Papa on the plane to Lahore. I had dressed extremely modestly for the day, mostly for the sake of comfort, in a long black kurta with light embroidery and a broad blue shawl draped over my head. (I had packed a nicer dress to change into in the evening, as most Pakistanis seem to do whenever there are evening activities.) I have come to enjoy airports in Pakistan as a little challenge to myself, to see how much I am able to blend into the crowd. Almost everyone in a Pakistani airport is Pakistani, the only exceptions being the occasional East Asian tourist or white American/European businessman traveling for work reasons -- and that latter type is instantly identifiable and never tries to blend in at all. But I always greet the airport officials with “assalaam-o-alaikum” and then do my best to get through my transaction in Urdu. “Aaj kahaan jaayengey aap?” is the typical question (“where are you going today?”). And I can answer this in Urdu as well, in this case: “main Lahore jaayungi.” And this is what I said to the two ladies who were security screeners in Sukkur. This is something I find very pleasant about airports in Islamic countries, namely that women are screened separately and by other women, behind a curtain, so they do not ever have to feel exposed. The resulting atmosphere for female travelers is a bit gentler and kinder than in my airports in the US. The women screening me in Sukkur were especially friendly as I told them I was headed to Lahore with my Sindhi Papa. “But you are Afghani?” one of them asked me. “No no, Amriki,” I answered, though smiling broadly to have been mistaken in this way. Afghans and Pathans (who are ethnically Afghan but Pakistani by nationality, living mostly in the northern parts of the country) are typically fair-skinned and often have light eyes as well, so it is no great surprise that I often get asked if I am a Pathan. But it pleases me to no end that I am able to disguise my American-ness to that extent. I explained to the ladies that I have been spiritually adopted by a Sindhi family, and that I was traveling to Lahore with my Papa. A little later they saw us across the room as we were waiting in a different queue for something or other. I must have said something to Papa that caused him to laugh and squeeze my nose in mock-disapproval. I noticed that the ladies had seen this, and I called out to them: “woh mera baap hai!” (He is my father.) “Haan haan!” they called back, laughing and grinning. We had arrived early at the airport, and in the hour or so before our flight the small waiting room filled up almost entirely with Papa’s colleagues -- doctors who were also going to the same cardiology conference. But I will not devote too much more time to the Sukkur airport, since Lahore is our destination here. And we arrived there on time after our very short flight--and so, for the first time, I found myself in Punjab province. “Sweet EM!” said Papa with a giggle. “Do you now feel like you have been born?” I looked out of the little airplane windows and towards the Lahore airport, which is a charming red brick structure that faintly imitates the red tones of the old city. “No, not yet, Papa,” I responded. “I don’t think I will be properly born until I see the city itself.” “WELL THEN!” Papa guffawed. “Someone must be having terrible labor pains for you now!” And we both laughed. All the passengers from the plane descended to the tarmac and filed towards a couple of buses that were waiting to carry us the rest of the way. Papa and I were the first to climb onto the second bus, and so Papa sat us down in seats directly facing the open doors and decided that we would be the welcoming committee. “Welcome!!” he grinned broadly to each of the unsuspecting passengers as they joined us on the bus. “Welcome to my bus!! …. Bhalee karey aaya! … Khush amadeed!” (I overflowed with giggles.) Soon we were in a cab winding its way out of the airport territory and towards the city. And this road was one of the places where I could feel most tangibly that I was not in Sindh anymore. No more of the rough and dusty, uneven, unpainted roads that surround even the urban parts of my home province. These roads leading into Lahore were almost indistinguishable from roads that I am used to in the USA: smooth, broad, recently paved, and -- to my great amazement -- marked with painted lines and flanked by not infrequent road and traffic signs, even stoplights. In most parts of Sindh, traffic is a free-for-all of sometimes mind-boggling proportions. I can’t recall seeing a traffic light anywhere in Sindh (for one thing, that would require electricity! and I can understand that it might not feel like a priority for citizens who are already dealing with four-plus hours of loadshedding each day). In short, there can be no doubt that there is more money allocated to infrastructure in Punjab than in Sindh -- and more in Lahore than in Karachi. But I do need to temper these observations with the proviso that the road from the airport leading into one of the most prosperous parts of Lahore is not representative of all Punjabi roads -- special attention must obviously be given to a road like this that will see so many visitors. Nonetheless, the contrast to Karachi roads is instantly appreciable. On the whole, one can also instantly recognize that Lahore is a place accustomed to receiving foreign visitors. Of Pakistan’s major cities, Lahore has the largest draw of tourists, primarily for the sake of the historic Mughal architecture (which was also my main reason to be excited for this visit). In Sindh, even in Karachi, a foreign tourist like myself is an unusual sight; but cosmopolitan Lahore is not surprised at foreigners and is used to dealing with them. For me personally, I enjoy my exceptional presence in Sindh, and the way I am greeted with surprise and amazement there, and had to admit to myself that I missed that instant-specialness now that I was a much more commonplace kind of visitor. But that is a guilty confession on my part. My Sindh also deserves to be visited by people from the whole world, and I hope that it will be, even though I selfishly wish I could always keep that extraordinary experience of being an Amriki-Sindhiyani to myself alone.  Papa naps on the sofa, PC Lahore. Papa naps on the sofa, PC Lahore. We were headed toward the Pearl Continental Hotel -- PC Lahore as it is more frequently called -- which I was told was one of the finest hotels in Pakistan. (It was our good fortune that this happened to be the conference hotel!) And the most immediately apparent luxury that this hotel offers is a very high degree of security. Our cab passed through a checkpoint gate where it was required to open its trunk for inspection by various security officers and sniffing dogs. Each car is subjected to the same upon entrance and each re-entrance. We were dropped off a few steps from the main hotel entrance, where a pair of elegantly outfitted guards pointed us to the correct doorway with their gloved hands. They were extremely tall gentlemen made to seem positively gigantic in that they wore military-style hats with great fans perched atop them. We followed their direction towards a doorway with a metal detector and a separate scanner through which all purses and suitcases had to be passed. Despite all this elaborate screening, the atmosphere was genuinely hospitable, just as I have always found in Pakistan. The guards and attendants showed particular respect to Papa, bowing to him and showering him with words of admiration. After we passed by, I asked Papa if he knew those guards, and was surprised to find that he did not. Then why, I asked, were they so especially demonstrative? “It is simply because they recognize me as a professor,” he explained, and asked why it should surprise me. I told him that in America a professor does not command any special respect among strangers. My American father is also a professor, and I have spent the majority of my life in close association with professors, and have never seen such a display of respect for any of them. Then again, elaborate displays of respect for anyone are uncommon in America, where the general social philosophy tends to resist overt hierarchies. I was a bit tired at this point, having gotten up very early in the morning, so our plan was to check into the room and take a nap before lunch and sightseeing. We were brought up to a beautiful room, but found that it did not have the requested two twin beds but rather only one larger bed. Papa explained to the bellman that twin beds were necessary and that I was his daughter. The bellman looked embarrassed and promised that a different room would be found for us soon. A few minutes later we were told that the new room was being cleaned and prepared for us and it would be ready in a short while. In the meantime, Papa thought it wise that we go ahead and rest, saying that I should take the bed while he rested on the sofa. Actually, the only reason I include this trivial paragraph in my account at all is to explain this sweet photograph that I took of Papa resting on that sofa, using my blue shawl as a blanket. After resting a while, then relocating to the other room, then having a quick lunch among cardiologists in one of the dining rooms, Papa and I dusted off our cameras and set out for the city. “LAHORE QILA!” Papa directed our cab driver as we passed outside of the hotel gate. The cabbie nodded, and I wondered how many hundreds of times he has probably driven that particular stretch of road between PC Lahore and the grand and enormous Qila (fort), which is one of the major pieces of the Mughal legacy of the city. It was built in the late 16th century during the reign of Emperor Akbar--the “Mughal-e-azam” or Great Mughal, after whom one of my favorite Bollywood movies is named--with some additions made by subsequent Mughal rulers. I credit the elegance of Mughal design with the awakening of my very earliest interest in South Asian culture (see this early blog entry), but prior to visiting Lahore I had only once actually been in the presence of any Mughal architecture, in the form of the Shah Jahan Mosque of Thatta (see this entry). And some day I must travel to the Taj Mahal in India, which I have been convinced ever since early childhood is certainly the most beautiful man-made structure on the whole of our planet. But for now I was happy to be in Lahore, where the vast majority of Pakistan’s Mughal treasures are located. And I was not to be disappointed. Our driver dropped us at a stretch of wide, bleak pavement, from which we could see the high walls of the fort rising on our left. The beauty of the place, at this point, was quite concealed from our view by those walls. This had the same dismal feel that the outer edges of great sites anywhere tend to have, after they become tourist destinations; it felt like a long and dull walk (though it actually was only a few minutes) past empty vendors’ stalls over rocky gravel until we had woven our way into the actual complex.  Having turned a corner and ascended a bit of a hill, we suddenly came in view of the Alamgiri Gate, which was glowing a beautiful pale pink in the evening sunlight. That gate is named for Emperor Aurangzeb (also called Alamgir, which translates to the rather thrilling phrase “universe seizer”), who was the sixth Mughal emperor, son of Shah Jahan. The gate seems to exert a gravitational pull and we wanted to move towards it and admire it, but the path was blocked (you can see a sign in the photo which says, in Urdu, “yeh rasta band hai” -- “this way is closed”). I think Papa probably would have ignored that sign had it not been for an alert armed guard and various others telling us that we had to enter through a side portal to our left.  Hathi Paer, where elephants trod. Hathi Paer, where elephants trod. So we obeyed and veered in the direction where we were pointed, and we entered past a wall that was crumbling with age but still brilliant in its ornamentation. We passed through a large arched gateway, certainly large enough for elephants in a triumphal procession, in which the Emperor would have liked to arrive--in this case Shah Jahan, during whose reign this gate was built. Inside the gate we ascended the broad stairway, the Hathi Paer (elephant stairway), lined with a gallery of now-closed-in windows of various sizes. Papa told me that prisoners would have been displayed in those spaces when the Emperor was coming in and out, so that he could feel his own power in a tangible way. Perhaps he would occasionally pardon one or the other of them in a display of mercy.  Dry reflecting pool. Dry reflecting pool. The Elephant Stairs led us up to a series of courtyards, the first of which was strewn with colored blankets and wooden pallets, evidently for some musical event later in the evening. A little bit further on was a broader and more magnificent courtyard, flanked with unique treasures on each side.  Imagining the fullness of the pools... Imagining the fullness of the pools... In the center was a square platform, around which was carved out a shallow circle, which must have once been kept filled with water. All around the Mughal structures that I visited in this short trip I found such structures, almost all dry now: shallow pools and sometimes narrow channels that must have once gleamed with glorious reflections of the imperial architecture all around. I had to think again of scenes from Mughal-e-azam, in which such pools and rivulets are revived with their dreamlike waters to exquisite effect. Certainly it would be easy to romanticize the Moghuls, and I am guilty of this, I know. But if I can be forgiven for that fault, it is because the the beauty of their structures is not at all a fantasy, but a concrete reality. Again and again I found that the way the sunlight falls upon these gates and archways and walls (even when crumbled) and pools (even when dry!) is not only elegant but sublime. To see these places in their full opulence of centuries past must have been almost more dazzling than the eyes can handle. Straight ahead of us, in the direction of the sunlight, was the “Naulakha Pavilion,” whose name, I have since learned, actually refers to the price of building it (9 lakhs rupees!). And inside that exquisite marble pavilion, with its drooplingly curved roof and intricate carvings, there stood an Emperor. Well… there stood a gentleman who has acquired the enviable job of standing in this place wearing the dress of an Emperor. Obviously it is a gimmick for the tourists (like myself), but what a charming gimmick nonetheless. Because the space is so unremittingly beautiful, and one cannot help but imagine emperors and courtiers and all the rest in any case. I certainly didn’t pass up the chance to take our acting Emperor’s photograph, or to capture Papa at his side. Being offered the Emperor’s sword, Papa quite daringly (and to my own dismay) grasped it and posed as if he were ready to behead the Mughal monarch. I urged him against such a treasonous display and we took our leave of the Emperor and of the pavilion. Photos using only natural light.... genius of the Mughal architects. On an adjacent side of this courtyard was an even more exciting structure, the Sheesh Mahal, which translates to “Glass Palace” -- a room in which the walls and ceiling are bedecked with thousands of glistening mirror tiles. (By the way, a note to any Westerners reading this. We have all been mispronouncing the word Mahal -- as in Taj Mahal -- for a long time. It isn’t Mahaaal, which is what we always want to say. The two syllables are roughly equal in both stress and vowel quality, so it is something more like “meh-hell.”) The glass tiles are cloudy now, but probably there was a time when you could see your face reflected a hundred times in those spiralling mosaics. It seemed at first that the hall itself was closed to visitors, but it turned out that you merely had to pay a small fee to the attendant in order to be let onto that fine floor. As a result, we were the only ones in that space at the moment, which opened for us a lovely photographic opportunity.  Minar-e-Pakistan. Minar-e-Pakistan. Through the windows of one of the mahal’s side parlors we could also see the towering point of the Minar-e-Pakistan, which is one of Lahore’s more recent major landmarks. But both the Qila that we were standing in and the Minar visible in the window are monuments to Muslim rule in the region, in different parts of history, and in very different circumstances. The Mughals, of course, were conquerors originating from other lands, and though they were by no means the first Muslims in South Asia (the religion had been established broadly for centuries before the first Mughal, Babur, arrived in the early 16th century), they were the first to make Islam the ruling religion, and to establish an Islamic empire in the Indian subcontinent. The Minar-e-Pakistan, meanwhile, commemorates the 1940 decision of the All-India Muslim League to create a new nation for the Muslim population; in other words, to establish Pakistan itself.  The beckoning domes of the Badshahi Mosque. The beckoning domes of the Badshahi Mosque. But let us return to the Mughal past for a while longer. Across the courtyard from the Sheesh Mahal, the light of the sinking sun was streaming through the space between pillars, where distant minarets seemed to beckon to us. We followed that light for a brief but dazzling view of the Badshahi Masjid, with its glorious glinting domes. I was eager to proceed for towards the mosque, but there was still so much of the Qila that we had not seen, and which we now passed through in haste, knowing that we didn’t have much sunlight left. We passed first through a garden courtyard known as the Diwaan-e-Khaas -- the “Special” Divan -- where the royals could have an audience with privileged subjects and persons of importance. Neighboring that was the much larger Diwaan-e-Aam: the Divan for Commoners, where the Emperor could hear petitions from the public at large. He would of course not have to mix with the public: he would appear on a balcony raised some 8 feet or so above the floor, and look down upon the gathered masses. After attending to the commoners, the Emperor could again disappear into the building and exit by way of his Private Divan, nestled behind and entirely away from the view of the public gallery.  Parrots of the Divan-e-aam. Parrots of the Divan-e-aam. But the Diwaan-e-Aam, while far simpler and less ornate, is also not without its charms, overlooking an expansive lawn which even now is elegantly tended. And in the rafters of the open pavilion, beautiful green parrots fly freely and call to one another. It never ceases to amaze me that a bird as exotic (in my eyes) as a parrot could be simply wild and at home in any place, but they seem perfectly at home among the royal palaces of the Mughals. These parts of the fort we saw only briefly, conscious of that rapidly falling sun and eager to get over to the mosque. The front entrance of the mosque faces that beautiful Alamgiri Gate that we had seen at the beginning, and which was still now glowing with pearly sunlight, if a little less brightly. The Badshahi Mosque was also built during the reign of Aurangzeb (Alamgir), who must have exulted in the beauty of these breathtaking structures when they were new.  Where "permission" must be sought. Where "permission" must be sought. We left out shoes in the designated spot and joined the throng of other visitors who also wanted to see the mosque while there was still light left, and who were gradually sifting in through the security checkpoints in the gateway. We were surprised to be halted by the guards, who informed us that photography was not allowed inside the gate “except by special permission.” Both Papa and I would be frustrated beyond measure not to be allowed to exercise our shutter fingers while in the presence of such beauty as this mosque, so Papa promptly asked how he could go about obtaining the necessary “special permission.” The guard pointed to a small office halfway across the lawn. Papa instructed me to stay here while he went as quickly as he could (already the sun had fallen below the horizon) and secure our permission. He was barefoot, but that wasn’t going to stop him, Nonetheless, the guard called to him and pointed to a pair of communal flip-flops that must get used every day for exactly this purpose. Papa slid his feet into them--they were too small and looked uncomfortable, but he didn’t complain--and flip-flopped his way over to said office and back. Meanwhile I took this photo of the Alamgiri gate:  Mosque, and a dry reflecting pool here too. Mosque, and a dry reflecting pool here too. Five minutes later, Papa flipped and flopped his way back up the steps, permission slip in hand, and we thus entered the mosque’s courtyard as legitimate photo-takers. Evening was becoming cool, but the gently textured brick of the courtyard was still fairly warm under our feet. The sun had set completely, but the sky was still light, a gentle pinkish color. Or perhaps it only seemed pink in a response to the ruddy hue of the mosque. There before us, across the expansive courtyard, stood that marvelous structure, with its scalloped archways and immense domes, which seem like globes, whole worlds unto themselves. As we wandered about, a pair of college-age girls asked to have their picture taken with me, apparently taking it from my unusual complexion that I must be a foreigner. I was happy to oblige, secretly pleased to play the role of the ‘exciting guest’ once again. This although Papa laughingly told them, in Urdu, that his daughter is not a foreigner, but Pakistani and Sindhiyani! I’m not sure whether they believed him or not. We made our way along the outer walls, taking photos here and there, and then curved inward the mosque. “SOON WILL BE PRAYER TIME,” said Papa as we stepped inside one of the archways at the right side of the building. It occurred to me that I should capture that moment on video, so I quickly switched the settings on my camera and hit ‘record.’ And, sure enough, a clear and luminous voice soon rang out over invisible speakers, as if emanating from the walls themselves. “ALLAH o akbar, ALLAH o akbar,” it began -- the familiar words and tones, but sung more beautifully and distinctly than I had ever heard before. The azaan (call to prayer) is one of the things I always miss the most when I am not in Pakistan: the way the voices mark the day with their melody, drawing the spirit inward and somehow outward and upward at the same time. In Larkana, the azaan is a raucous combination of many different muezzins calling from many different speakers of many different minarets. Even here at Lahore’s grand mosque, multiple voices do color the background of the sound. But the focus here is on one beautiful voice and one sublime chant. The footage I recorded of the azaan is not of the finest quality, given that I was using a handheld camera with only its internal microphone. But I am glad to have gotten an audio-visual document of that moment, and I hope that you will be able to get a sense of the beauty of this extraordinary mosque at prayer time. Not long after this, we headed back out into the night, towards the car and driver who were waiting for us. Had the sun not set and had I not been so exhausted from all our wanderings, I would have wanted to explore so much more--I feel that I have scarcely been able to look below the surface of these complex and layered sites. But my energies are limited and so are the hours of daylight, and I was happy to rest myself that evening. We went to bed early -- I in that lovely room all to myself, and Papa in the second bed of his colleague’s room down the hallway. And that seems a wise place to end this part of the travelogue. By the next, I will be rested again and ready to see several other Mughal wonders before heading off to an even briefer visit to Islamabad. More photos from the Lahore Fort and Badshahi Mosque.....

5 Comments

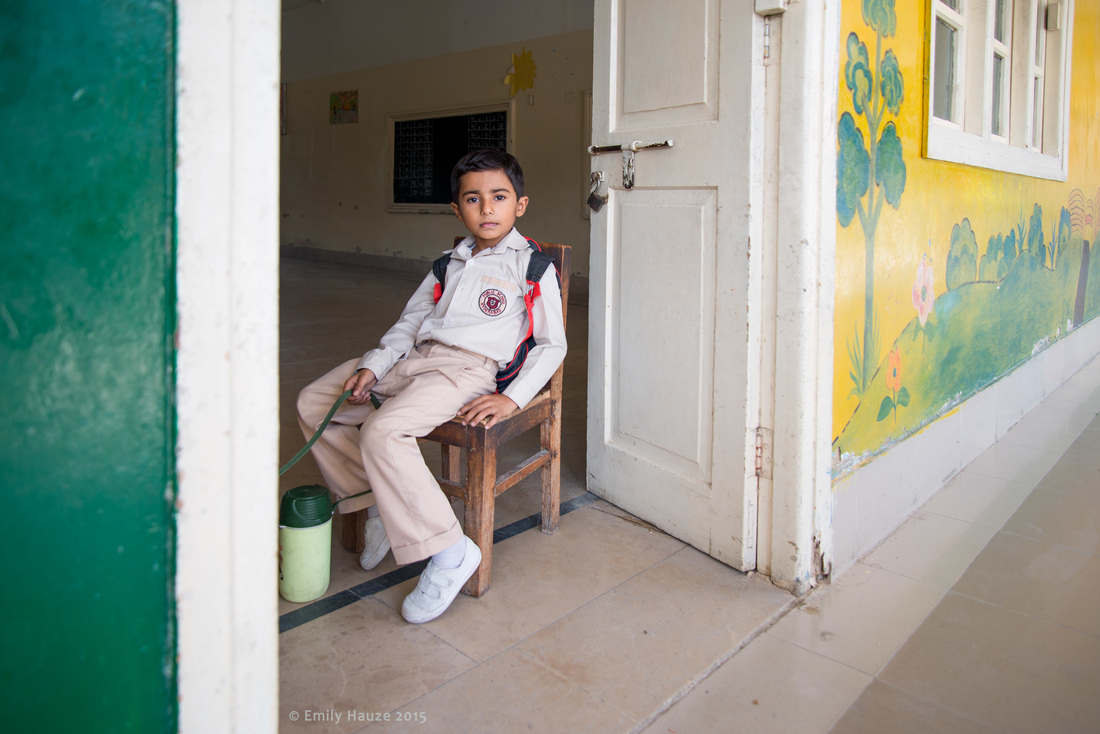

I had slept a bit late on that particular Friday afternoon, and Inam had already left for the office when I came out to have my breakfast. But Inam’s wife, Farzana, tended to me with great care and gentleness, as she always does. Her skills in English are probably only a little better than mine in Sindhi, so communicating together is a good challenge for both of us. I hope my Sindhi will be stronger by the next time I get to see her, but even as it is, we are already able to communicate a fair amount together. On that morning I recall that Farzana told me some beautiful things about her faith. She explained that we are made up of two parts, spirit (rooh) and dust (khak), and that it is the desire of every Muslim for the part that is dust to find its rest in Medina, the Prophet’s city. As for the part that is spirit -- that will be reunited with what is Holy, no matter where the dust comes to rest. These things she told me in a combination of Sindhi and Urdu, as I listened carefully, asking her often to explain certain words. And I sipped my milky tea and ate my fried egg with Sindhi bread, and the two budgies, one blue and one green (or is it yellow?), chattered sweetly in their cage in the corner of the airy living room. As I was finishing up my breakfast, Farzana got a call from Inam, who had been making arrangements for my visit that morning to the Public School Hyderabad. I had two particular reasons to be excited about this visit, namely two people: my adi (respected sister) Shagufta Shah, who is on the senior faculty of the school as an art teacher, and also Priya, Inam’s eldest daughter, who has also been teaching there (in a different section) in the couple of years since her graduation from university. From adi Shagufta I had been hearing about the merits as well as the tribulations of this venerable institution for quite some time. And in my previous trip to Hyderabad, when I first met Priya, I learned about the school from her perspective, though at that stage I had not realized that the school Priya was describing was in fact the same one that I already knew about through adi Shagufta. In both cases I had hoped to visit the school, and so I was all the more delighted when I realized on this trip that the schools were one and the same. The plan now was that I would first go and see adi Shagufta in the senior girls’ section, and she would show me around her part of the school, and eventually lead me to the section for the younger boys, where we would find Priya. Since it was a Friday, which is the holy day, classes would let out around noontime. This meant that I needed to get going quickly -- it was already mid-morning -- if I wanted to see any of the classes still in session. So I grabbed my purse and wrapped myself in my dupatta and started out the door. Farzana pressed a piece of paper into my hand as I left, saying, “Shah sahib khe ddey” (‘give this to Shah sahib’). It was a little note written in Sindhi explaining that the driver should go to the main gate of the school and ask for Shagufta Shah. The driver, whose first name I don’t know since everyone simply calls him “Shah sahib,” was already familiar to me -- he is Inam’s most trusted and reliable driver, so I had no qualms about being taken into the city otherwise alone in his car. But he speaks little English, so it was kind of Farzana to write him a note in case I might have difficulty telling him where I needed to go. Note in hand, I trotted down the stairs of Inam’s house and through the courtyard to where the car was waiting for me. Shah sahib, a soft-spoken man with a gentle face, held the car door open for me and closed it after I had succeeded in gathering my various folds of cloth--dupatta and dress--inside the car. Pakistani readers may wonder why I describe such banal details, but I think my average Western reader will understand what is special about them. In our daily lives we rarely experience these touches of civility and service. The idea of “having a driver” is something reserved only for the very rich, and no one would expect any chivalry from an American taxi driver. Once Shah sahib was situated behind the wheel, I handed him the note and said something like, “Public School halandaaseen.” He looked at the paper and nodded, “Ji ha, madam.” Though Inam’s house is out a little ways from the hustle and bustle of the city, it was still only a short drive to the heart of town where the school is located, via the “Auto Bhan” road. (That road was of course named to suggest the high-speed German Autobahn highways, though the name has been very lightly misspelled. Cars on the Hyderabadi Auto Bhan, however, do not reach such break-neck speeds, as there is simply not enough room on the road for that in this densely-packed and lively city.) When we reached the gate of the main section of the school, we found it guarded by a pair of armed policemen. This is not the least bit unusual -- as I have mentioned in other blog entries, nearly everything in Pakistan is patrolled by armed guards. Although that presents an initial shock to the Western traveler, it is surprising how quickly one becomes accustomed to it, and somehow the guards never seem menacing, despite their heavy weaponry. Shah sahib rolled down the window and asked the guards how he should proceed in order to meet with Madam Shagufta Shah. Adi Shagufta is a well-known personality at the school, so there was no doubt that the guard would know how to direct us. From the glance that he gave me, it seemed possible also that he knew who I was, and why I would be coming -- because through my connection with adi Shagufta on Facebook, I was already fairly well known in this school. He told us that we would find Madam in the Girl’s Section, and pointed us down along the road to a different gate. The school grounds are expansive enough to merit separate entrances to the boys’ and girls’ sections, it turns out. And beyond the senior boys’ and girls’ sections, there is yet another building, devoted to the younger children (elementary school age), which is where we would find Priya later.  Me with adi in the PSH auditorium. Me with adi in the PSH auditorium. Arriving at the second entrance, we inquired with a second set of guards, who told us we would find Madam Shagufta just beyond a nearby entrance. Shah sahib got out of the car to accompany me in case I had any trouble, but it turned out to be hardly necessary, because I spotted adi Shagufta through a window, in a front office, and we both waved excitedly as she hurried out to greet me. “Hoo’a munhnji pyaari adi aahey,” I explained to Shah sahib (‘she is my dear sister’), as she came out to give me a warm hug. It is a wonderful feeling to be welcomed into a new place where you are nonetheless already known and loved. I always feel proud in such moments -- especially if there are guards or other onlookers who might naturally be a bit suspicious or curious about what an outsider like me might be doing there. The mood always changes when I am greeted by those who know me -- and few could greet me with more love than my dear sister Shagufta. As her guest, I would command all the same respect that she does. She handed me a bouquet of bright flowers, beautifully bundled -- mostly blossoms of bougainvillea, I think, though somehow I didn’t manage to keep a picture of them. I do recall that they had been gathered and arranged from right there on the school grounds by one of the gardeners, and that they do that regularly for honored guests. Tending to those expansive school grounds is a large job, adi Shagufta told me, and the gardeners on staff work long hours and are paid very little, but still they put a great deal of love into their work. The campus is indeed lined with many flowering bushes and graceful trees, tended by the same hands which had prepared my bouquet. At this point we exchanged the same kinds of loving pleasantries that one might expect -- along with an exchange of gifts -- my Sindhi friends are generous beyond measure, and adi Shagufta is especially so. She gave me some beautifully stitched clothes (a dress and more), and a locally made dupatta, which she was pleased to see matched the simple traditional dress that I was wearing at the time. So I pulled off the dupatta that I had been wearing and replaced it with the new one, which you’ll see here in the photos. I gave her a diary sketchbook, because I know she is fond of sketching and thought she might like to record her visual thoughts in this way.  But we knew we should not spend too long chatting and giving gifts, because we wanted to see the classes before they let out for the day. As we set out into the hallway, we were joined by a tall and smiling woman who at once gave me a big hug, though I did not recognize her. “This is Asma,” said adi Shagufta, “but you know her already as Assyed Syed.” “Oh, of course! So nice to have a face to go with your name,” I said, and returned her hug. She was indeed known to me on Facebook, but she like many other Pakistani women does not use her own photograph on her profile (or even her precise name), which is why I had never seen her before. The reasons for such privacy among women on Facebook are complicated and varied -- sometimes it is societally induced, sometimes it is the behest of a father or husband that a woman not show herself, and sometimes it is simply modesty. I’m not sure which of these reasons keeps Asma from sharing her own picture online, but out of respect for it I will not share any pictures of her, even though she was our companion for the rest of this visit. (Adi Shagufta, meanwhile, has been very progressive in her stance on photographs online. For one thing, she knows that she is a public figure -- she is well-known in Sindh for her writing in many genres as well as for her artwork -- and she does not feel the need to keep her face hidden, and most of the time she does not cover her head with her dupatta. That does not mean, however, that she lacks modesty; she is instead a fine example of a different way in which traditional Islamic modesty can combine with more progressive and liberal views.)  Assalaam-o-alaikum! Assalaam-o-alaikum! We proceeded down a short corridor and towards a central courtyard, around which the girls’ classrooms are arranged on two levels. Like so much of the architecture in Sindh, there is a fluidity between what is indoors and what is outdoors. In a climate in which it is rarely cold or rainy, the focus is always on maximizing coolness and airiness. Behind windowpanes we could see the girls at their desks, writing and watching and listening. Perhaps they were doing these things less intently at this hour than they might have been earlier in the week -- after all, what schoolchildren don’t get excited about the imminent arrival of the weekend? But I didn’t notice any tell-tale signs of distraction or giddiness. The girls seemed focused on their learning. “Would you like to meet the students?” adi Shagufta asked me. I answered “of course,” and so we strolled right into the first classroom. To my great surprise, the students all stood up at once as we entered, and said in a slow and rhythmic unison: “Assalaam-o-alaikum!” “Walaikum assalaam,” I responded, no doubt smiling broadly. I realized at once that this must be a school custom so ingrained as to be completely automatic for the students -- but for me, such elaborate displays of respect and discipline are still a source of amazement. A group of young American students might be induced to say “good morning Mrs. So-and-So” on command, but only sometimes, and usually grudgingly. But for them to stand up immediately upon a guest’s entrance into the room and offer the greeting cheerfully -- that would be extremely unusual. The girls all wear uniforms -- which is not unheard of in American private schools, though it is very uncommon. In Pakistan, however, school uniforms are nearly universal, and from what I’ve seen, they seem quite similar from school to school. At PSH, the girls wear a simple grey suit with white shalwar pants and a white stole, with the option of a hijab over their heads. Most girls I saw, perhaps surprisingly, did not cover their heads -- but since only women were present (apart from a few male teachers), there must not be much pressure to do so. (Notably, a much higher percentage of veiled heads is visible in my photograph of a math class, whose teacher is a man.) A sensible pocket at waist level bears the crest of the school. Under the grey kurta is a white blouse with a rounded collar and scalloped edges, which are visible both at the collar and on the cuffs, and which add a certain softness and quaintness. It seems to me these are also marks of Englishness -- and certainly the educational sphere is one of the places in which colonial heritage can be felt most strongly. I was first introduced to the teacher, who greeted me with a hug and did not seem to mind our interruption of her class. Then adi Shagufta turned to the class and introduced me to the girls. “Many of you will already be knowing Ms Emily Hauze from Facebook, especially if you are connected with me there,” she said. Many of the girls smiled and nodded. “Do any of you have any questions to ask Ms Emily? A blush of shyness came over most of them, but one girl in a middle row piped up, “Do you like Sindh?” To which I explained what my blog readers will already know well, which is that indeed I love Sindh and it is a second home to me. The girls giggled contentedly at my response. We repeated that same pattern of meeting-and-greeting in several other classrooms, and in each one I was pleased to be met with the same charming salute of “Assalaam-o-alaikum” from the students. We had a peek also in a couple of science labs, not currently in use. The chemistry lab was enchanting to my eyes -- very old-fashioned in appearance, with ancient-looking bottles of chemicals lined up on carrell shelves. There is something both good and bad to be said for the “modernizing” of classrooms. A comparable American chemistry lab would be fitted out with more digital devices, and any bottles of chemicals would be stored away in locked closets as per safety codes. The students might be able to perform more accurate experiments, and more safely, in the American setting, but at the same time, very few of the students would feel the magic of it--and the net result of learning is probably no higher. The older-seeming equipment of the PSH laboratory carries a hint of excitement, an invitation to learning and experimenting. For higher education, more advanced equipment would certainly be necessary -- but for the level of science needed to get teenagers interested, the chemistry lab I visited seemed ideal. I hope that the young women of Public School Hyderabad are indeed being inspired to advance in scientific fields.  Prefects display a fine sash. Prefects display a fine sash. A little further down the hallway we came to a classroom in which some of the older girls were gathered for their last class of the day. As before, they all stood up to greet me, and remained standing until I had left. Among this group I saw that a few of the girls wore sashes across their kurtas indicating that they were Prefects (or the Head Prefect, Deputy Head Prefect, etc). This also caught my eye as something very different from American culture, at least as it was in my own youth. Although we had an Honor Council and a group of student Proctors in my high school, and it was a source of pride to be in either group, we never wore any kind of badge to announce the privilege, even if we secretly would have liked to. For us, high school years were all about blending in with the crowd and trying to be as un-unique as possible. A sash announcing a special status would have quickly become a point of derision and mockery (disguising the other students’ jealousy). It seems to me that in Pakistan, by contrast, rankings of this kind are held in more genuinely high esteem, and that a Prefect is someone who commands a degree of respect, rather than jealous mockery.  Craftwork gifts, student-made. Craftwork gifts, student-made. And finally we arrived in a hallway that was already very familiar to me from adi Shagufta’s Facebook timeline -- her art department. Some of the younger girls were in an art class at that moment, and we said a quick salaam to them before going to adi’s own office-studio at the end of the hallway. It is a large open space with a desk in one corner near the windows, which look out on adi’s familiar view of the open field and the ceramic-tiled roofs of the school building. The walls are lined with student art projects (and also some of adi’s own drawings), arranged neatly with a gallerist’s sensibilities. One long table at the left side of the room was covered with student craft projects -- purses, fans, and other decorations designed loosely with Sindhi traditional themes and young girls’ imaginations. Adi told me that these were to be given to guests, and that I would be welcome to take any of them. Trying not to linger too long on my choice, I picked out a small and simple purse and an ajrak-patterned fan. On the other side of the room was a cabinet containing more student creations: decorative boxes and dolls and vases filled with tiny arrangements of colored baubles suspended in gel. I was offered any of these that I might like as well, but, worrying for the weight of my suitcases, I had to decline. (I try to leave space in my suitcases for gifts whenever I travel to Sindh, but I invariably end up filling them to the brim nonetheless, because of the extraordinary generosity of Sindhi people.)  Junior's Section, exterior. Junior's Section, exterior. By this time, classes had all let out, and the building was gradually becoming quieter and more empty. I asked if we ought to be heading over to the Junior Section, where Priya would probably be waiting for us. There was some deliberation as to whether we should find our driver or simply walk there, but it is actually a very short distance, so adi and Asma did not argue when I urged that we should walk. In the hotter months, I’m sure that even that small walk can feel like a trek in the beating sun, but on this day we walked comfortably together down the broad alley and then across a grassy path which forms a short cut to the boys’ section and the junior section, both set apart from the girls’ section. The area around the Junior Section is charmingly landscaped, with sculpted hedges and immense flowering trees that blanket the building itself in their colorful shade. A few children were milling about, meeting their parents, but mostly it was quiet. We inquired inside at an administrator’s office as to where we might find Miss Priya, and were told that she was in a meeting with the principal.  Peeking Juniors Peeking Juniors So we continued to wander. I found that the Junior Section is also arranged around a central courtyard, though the classrooms comprise only a single storey on all sides. The corridors facing onto the courtyard are lined with rounded pillars, some of them painted in bright colors, and interspersed with hanging flowers. Some of the walls are painted with fanciful scenes. Though most of the children had left, a few giggling faces peered out at me from an open window along one of the walls. Luckily I was just quick enough to snap their picture before they vanished again into their classroom. Down a little further, I found another boy, who was sitting on a chair in the doorway of his classroom, waiting for his parents. He was an especially beautiful child, sitting perfectly still, with a wistful and air of quiet around him. He didn’t seem to mind as I knelt to take his photo, and his expression remained peaceful. I wondered what sorts of childhood stories might be playing in his mind as he remained statue-still there in his chair.  Soon we left the Junior Section and continued to the Boys’ Section, which is the oldest of the buildings, and features the imposing clock tower, which has become a symbol of the school. On our way, however, I was in for a surprise, when Asma asked if wanted to see the Zoo! A school zoo? I wondered, never having encountered such a thing. But there indeed it was, another enclosed courtyard lined with cages containing a few animals -- mainly a monkey, but also some colorful birds, and many geese and ducks wandering around the center. I told my companions that if there had been a zoo at my own school, I probably would have spent countless hours there.  hikro ddingo bholrro. hikro ddingo bholrro. Even in this moment I was tempted to linger in the little zoo, communicating with that solemn monkey who watched us knowingly from his cage. At one random moment the monkey burst forth with a huge shout, causing us three women to jump in surprise and then burst into laughter. Asma explained that he always does that, and that he’s a very naughty monkey.  Quick glimpse of the Boys' Section. Quick glimpse of the Boys' Section. We did not hover too long in front of the monkey cage, conscious of the advancing hour. We made our way onward to the Boys’ Section, where Priya had been meeting with the Principal. She was just getting out of that meeting as we arrived. I introduced Priya to adi Shagufta -- the two of them knew each other from a distance, but hadn’t had any real contact, since they work in different sections of the school. I felt pleased to be a connection between these two women, coming as I do from all the way on the other side of the world. And when Priya mentioned a bit later that she had in fact always been an admirer of Shagufta’s, having read and loved her novels years ago, my own feeling of delight at connection rose even higher.  Principal's office. Principal's office. By this time word had also reached the Principal that a foreign guest was here on campus, and we were all invited into his office for tea. Principal Muhammad Youssef is a distinguished-looking gentleman with a love of literature and considerable eloquence in speaking English. I hardly needed to introduce myself, because it turns out he knows Papa Saeed, though I can’t now remember what caused their paths to cross in the past. Soon after we sat down, a servant appeared carrying slim glasses with two kinds of sugary juice, one green (lime?) and the other an almost milky white (lemon?), Pakistani colors of course. Tea followed soon after, and I apparently proved myself as a ‘true Sindhiyani’ in the eyes of Principal Youssef when he saw me automatically dip my cookie into the tea before taking a bite. Certain customary behaviors come to me instinctively, I explained to him, and in other cases they come from close observation--and when I pull it off successfully, there is none more pleased than I. And, once again, my recounting of a visit ends in a moment of shared tea and Sindhi hospitality. (After this short meeting with the Principal, we all piled into Shah sahib’s vehicle once again, and he dropped adi Shagufta and Asma off at their respective homes before delivering Priya and me back to Inam.) In this case, however, I am aware that I haven’t told the whole story, and the omissions weigh heavily on my mind. I have not intentionally obscured any harsh truths, but have perhaps avoided them out of an excess of caution, because I do not yet know enough about them to evaluate them fairly. What I am hinting at here are problems in the administration--issues of corruption and ineptitude, which are common to all levels of Sindhi bureaucracy to varying degrees, and education is an area in which corruption is especially deep-seated. I was told by various teachers at Public School Hyderabad, for example, that they often have to go without their own paychecks for months at a time, not due to an actual shortage of funds but due to some administrative inability to allocated the funds at the right time. Months with no salary at all -- and the salary that they do receive is extremely humble, even though they are teaching in one of the most elite schools in the second-most important city in Sindh. One can only imagine what injustices, by comparison, are faced by teachers and staff at schools of less privilege. Further there is a history of nepotism and cronyism and unfair hirings and firings -- all the same pains that chronically afflict so many areas of life in my beloved Sindh. So why didn’t I spend more time talking about them here in this surprisingly long account of my visit? Two main reasons. The first is that I simply do not know enough about them to speak authoritatively -- I don’t know who is to blame, I don’t know the extent of the problems, and it would take a lot more investigative journalism than I am capable of doing in a 2-hour visit in order to report fairly on them. And secondly, I don’t feel that investigative journalism of that sort is my main purpose. I do not like to turn away from harsh realities -- but nonetheless, my inner calling is to celebrate what I find in Sindh. The problems are everywhere -- I can’t and don’t want to hide from them. But still I love what I see. I love what is shown to me. At Public School Hyderabad, I saw dozens of beautiful young faces whose eyes were bright with learning. I saw teachers who work hard to offer the gift of knowledge to those young ones who come to them. I saw gardens tended by unseen hands of gardeners who get paid almost nothing, yet keep countless flowers blooming. I saw cleanliness and discipline and passion and creativity. Perhaps in the future I will have cause to investigate the problems of the school or other educational institutions more deeply. For now, my primary message highlights what is going well: learning is alive. Additional photos from Public School Hyderabad: So far, out of my three trips to Pakistan, my husband Andrew has only been able to accompany me once. But that was enough for him to have many adventures of his own. I asked him to write down the story of his last day in Pakistan, which was especially action-packed. He has kindly obliged... his writing follows below. ~Emily Hauze My wife, Emily, is the adventurer in our house. She has spent almost a quarter of the last year traveling in Pakistan, and, while I loved my short visit there and look forward to returning, I am, by nature, much more of a homebody. I generally prefer to be at home and, as a pronounced introvert, I do best interacting with those I have known for a long time. For the last nine-and-a-half years I have taught at the same small college in a small town in Pennsylvania, the same college that Emily and I both attended. I tend to prefer slow, gradual change. On this last day of 2015, though, it seems appropriate to recall December 31, 2014, a day that was, without question, the most adventurous, varied, and unexpected of my life. New Year’s Eve was my eighth day in Pakistan with Emily. It was our first trip there (she memorably recounts our journey in her first four blog entries). I had had a wonderful time. Though I was quite sick for about three days at the start of the trip, I was given such extraordinary care by the Sangi family that I look back on the whole trip with an enormous sense of joy and gratitude. Neither of us had met anyone we visited on that trip in person before: our sole interactions had been through Facebook and, with the Sangis, Skype calls. Yet, by the end of the trip, I was known as “Andrew Sangi Hauze,” and I truly felt a member of the family. Though Emily would stay in Pakistan until the middle of January, I needed to come back to the U.S. to work, and so, on New Year’s Eve, the time had come for my journey home. However, as with every other aspect of our trip, the journey would not be complete without some intensive sight-seeing and hourly surprises along the way! The day started in the Sangi house in Larkana with several delicious cups of milky tea and sad goodbyes to all of the Sangis. In just a few days they had become my second family I felt amazingly close to each of them, and I was sad to leave them when we’d only just begun to know one another. I was to fly to Karachi from Sukkur, a city about an hour-and-a-half from Larkana. I was a bit nervous about this, as it would mean taking a very small plane (we had driven from Karachi to Larkana initially), and it didn’t seem that the ticket had actually been purchased yet. (It was difficult to get a clear answer from Papa Saeed on the exact status of the ticket, but his friend and travel agent was calling him quite frequently that day!)  Papa and Sachal's admirably focused devotee. Papa and Sachal's admirably focused devotee. Before flying, though, Papa Saeed wanted me to see some more sights, and so we set off down the road for the shrine of the Sindhi poet Sachal Sarmast. (Papa was very concerned that my visit was so short, and so he kindly made certain that I saw an amazing number of Sindh’s many attractions during my stay.) The shrine, while on a simple, unprepossessing road, is remarkably beautiful. The vivid blues and yellows of the tiles create patterns of great complexity and overwhelming loveliness. Before we approached the shrine, though, we were tempted by street vendors with their wares spread out on blankets before the entrance to the shrine. We bought some baubles for some of our young friends and family at home, and Papa Saeed bought candies for our journey that day. Next to the vendors was a musician with a fine voice, singing to honor Sachal Sarmast and accompanying himself on a tamboora and, sometimes, with jangles as well. Papa Saeed is never one to let such a musical opportunity go by: he sat down by the musician, gave him an offering, and asked if he might try his tamboora and jangles. The man went on singing, accompanied by Papa’s improvisations, while Emily played the jangles and worked to keep them all in time. Amazingly, in the midst of all of this, several young men approached and sat by us, greeted warmly by Papa. They were some of his many medical students who had also come to visit the shrine on that day, and so they sat with us until their professor was finished trying out the instruments! After paying our respects at the shrine with the magnificently fragrant rose garlands that seem to be omnipresent in Sindh, we were back in the car, on our way to the second sight of the day, the fort of Kot Diji. Papa tended to know the general direction in which to drive, but when he needed more precise directions, he would simply stop one of the many people walking by the side of the road and ask them the way. They were unfailingly kind and smiling (though often quite surprised to see us in the car!), and always pointed us in the right direction.  Elephant gate closed. Elephant gate closed. As we approached the fort of Kot Diji, we were awed by its imposing presence high on a hilltop. The fort in the 1780’s-1790’s by the rulers of the Talpur Dynasty. (It’s astonishing to think that the fort was being built as the American constitution was being written.) With three “elephant proof” doors (enormous wooden doors reinforced with metal and with gigantic spikes protruding toward oncoming traffic), the fort appears to be utterly impregnable. Perhaps, then, it’s no surprise that it was never actually attacked! Crouching to make our way through the smaller, human-sized openings within the spiked doors, I was struck that there was no one selling tickets or keeping watch over the fort or the safety of the visitors. We had quite a climb ahead of us, up mud brick steps and sandy paths, and yet there were no railings or safety precautions in sight. It was wonderful to visit such a site on our own, without the feeling that we were constrained by barriers, yet, at the same time, it is sad that the fort is generally not cared for by the government. (This regret that would be echoed later in the day by one of the descendants of the Talpur rulers.) There is litter everywhere, and one alcove we passed was filled with what sounded like thousands of bats! (We only know that they were bats because Papa Saeed stuck his camera in the doorway with the flash on and bravely snapped a picture.)  On the climb up to the fort, we met a couple with their baby girl who were also visiting the site (there were very few people there, in general). As so often, Papa Saeed boldly introduced them to his “American children.” While I would often be nervous at the mention of our nationality (as the United States has not exactly been kind to Pakistan in recent years), without fail the people of Sindh would smile and welcome us, usually with a look of gentle astonishment on their faces that we had made the journey. Often, too, they would reply, as this couple did, with “Thank you.” We tried to express that we were the ones who should be thankful, but there is no winning an argument with Sindhi hospitality. On our way back down, Emily posed for pictures with them and with their daughter.  Emily at Kot Diji Emily at Kot Diji To walk through Kot Diji is to exercise the imagination. In my lack of experience with historic forts, it felt like I had stepped onto an elaborate film set rather than an actual fort. With each step I could picture sword fights, military drills, commands shouted from one tower to the next, the enemy army approaching from the distance. While these were fanciful visions, it was uncanny to be utterly free in such a place. We stepped into the barracks used the soldiers. We walked past the enormous pool in which they would store months of drinking water in case of siege. We climbed to the highest ramparts and took pictures of Emily dancing on what seemed to be a stage (though it was probably a lookout tower). Our next stop was to be the Faiz Mahal. I knew little about it then, other than that it was some sort of palace. Once again, Papa Saeed would stop people on our way into the city of Khairpur to ask them the way to the Faiz Mahal. We soon found the walls surrounding the palace and could see the gentle pink color of its highest towers, and yet we could not find an entrance anywhere! Papa drove all around the block occupied by the palace several times until, finally, we found what seemed to be a back entrance gate. We drove through, parked, and were met by several guards (armed, as usual, with AK-47’s). Papa began to speak with them in rapid Sindhi, while Emily and I stood and smiled at them, hoping that this might help. They seemed quite skeptical of us at first, though Papa seemed to insist that one of them take his identity card inside. The man disappeared with Papa’s card while Papa explained to us that, as the royal family was at home, the palace was closed to visitors. (The royal family, I learned later, are the modern descendants of the Talpur dynasty who ruled the Khairpur region for centuries.) The guard soon returned and gestured that we should follow him. We did so, and were ushered onto a long lawn of beautiful green grass in front of a magnificent, if slightly worn, palace. There were some people gathered in chairs on the grass in the center of the lawn, and the guard led us to them. It then became clear that we were being introduced to Prince Mir Mehdi Raza Talpur, his brother-in-law, and his children. Emily and I were in a state of some shock (there had been no mention until now that we were to meet a prince). The prince was very kind and, after we were introduced, he looked at us with sad eyes and said: “And what has brought you to this God-forsaken land?” We explained a little bit of how we had come to Pakistan, and he was, like everyone else we had met, wonderfully welcoming. He and his children posed for some pictures with us. One of the boys had a toy, and I asked him if it was a lightsaber from the Star Wars films. His eyes lit up, and his father told him to “bring that lightsaber” so that it would be in the photos with us, too. It was a truly bizarre meeting of the culture of my childhood with the living cultural history of Pakistan. Slideshow: A young princeling brings his lightsaber. The Prince’s brother-in-law then kindly gave us a tour of the public areas of the castle, explaining to us the history of the family, and the agreement between the ruling family and Jinnah at Partition that was then breached after Jinnah’s death. Learning more of this history on my return to the U.S., I can understand even better the sadness in the Prince’s eyes. In his view, his family had exercised good governance over the region, making it one of the wealthiest, healthiest, and best educated in all of (what was then) India. Most of these advantages have now been lost. His father, who made the agreement with Jinnah, is still alive, though in ill health. It is amazing to think that he was somewhere in the palace while we visited, a living link to the royal past of Khairpur.  Emily, Andrew, a Sukkur policeman, and Sajid Mangi. Emily, Andrew, a Sukkur policeman, and Sajid Mangi. On our way out, Emily asked: “Papa, what was the Prince’s name, again?” Papa, with his impish grin on his face, said softly: “I … don’t … know?”, making it clear that he, just like us, had no idea that we would meet the royal family on that day! I learned that one must never underestimate Papa’s ability to charm his way into anything. I was getting a bit more nervous as the day wore on, as we only received confirmation that I did in fact have a plane ticket after we left the Faiz Mahal, though we still had to make the journey to the Sukkur airport. On our way to Sukkur, Papa was making arrangements with his friend Sajid Mangi to bring us dinner, and, as we drove down a road adjacent to the Indus, there was Sajid Mangi, waving to us from a motorcycle. He had brought us bags of fast food, which we took down to the beach to eat. Before we could reach the beach, though, we had to pass through metal detectors! At first I thought this might just be normal security, but, no, it was in fact due to the imminent arrival of a Hindu holy man whose arrival would be celebrated by many pilgrims visiting the Hindu temple just across the river. Many boats, loaded with pilgrims, were launching from the beach where we had arrived. We sat and at our chicken fingers as we watched the glimmering water and the brilliant colors of the shrine and the pilgrims’ clothes. Just as we finished eating, the holy man arrived, surrounded by a throng of people packed tightly around him. They all got into a launch and headed for the temple as we walked the other way, back towards our car. Unfortunately the extra activity had made the normally congested roads almost impassable, and I was getting more and more nervous that we might be stuck in a traffic jam and miss my flight. Fortunately my flight didn't leave Karachi until 3:30 AM (it was now about 5:00 pm), and so I anxiously calculated that, if necessary, someone could drive me to Karachi (though that journey itself would take at least seven hours, and there are bandits on the road at night). Fortunately we made it to the airport with time to spare. Papa had kindly purchased me a “first-class” ticket, which allowed us to use the VIP lounge at the airport. We were brought refreshing cups of tea, after which Emily and Papa had to leave to drive back to Larkana before it got too late. We said our goodbyes, and, while I didn’t relish the idea of leaving Emily for two more weeks, I was very comforted to know how well the Sangis would take care of her. Sajid Mangi kindly waited with me in the airport lounge until we were ushered onto the tarmac to meet the plane (and it was well over an hour, as the plane was considerably delayed — that it Sindhi hospitality for you!).

I hadn’t been in such a small propeller plane since I took a puddle-jumper from Reading, PA to Philadelphia in 1997, and I didn’t realize that I could not bring even my backpack to my seat, as it was too large. Fortunately, the gentleman sitting next to me noticed that I had nothing to read, and he offered to give me one of the English newspapers he had with him. Over the loud noise of the engine, he asked if it was my first time in Pakistan. I told him a bit of our story, and he told me that he was a Parliamentarian, heading back to Karachi as Parliament had been recalled on New Year’s Day. I had noticed him in the VIP lounge, and he had seemed to be a man preoccupied with much important business to conduct on his cell phone. I was pleased that he was so kind to me, and we wished one another well as we stepped off the plane in Karachi. While I would have preferred to sit in the Karachi airport, stationary and settled for the seven hours until my flight, I had one more taste of Pakistani hospitality to accept. The day before, Papa Saeed had taken us to visit a farm owned by Sarfraz Jatoi, a prominent lawyer in Sindh. I had spoken with Mr. Jatoi on the phone to thank him, and, when he asked about my travel plans, and I told him that I would be in Karachi the next day, he insisted that I come to dine with him. While very grateful for the hospitality, I had read in the parliamentarian’s newspaper on the airplane that New Year’s Eve would involve many road closings in Karachi, as well as “celebratory gunfire” at midnight. I wasn’t exactly excited about being out on the Karachi streets at this particular time of year. Mr. Jatoi had given me his number and told me to call him when we left Sukkur. When I called from the tarmac, he told me that he was sending a driver to meet me. Unfortunately, I could not see a driver anywhere, and my plane had been quite late. I looked everywhere for him, but soon found myself with my bags outside the Karachi airport, unsure of what to do. Ready to give up, I called Mr. Jatoi again. He told me that his driver had no cell phone, so there was no way of finding him, but he suggested that I take a taxi, and that he could give the driver directions over the phone. I tried several taxi stands, but they all had waits of at least 45 minutes (it was New Year’s Eve, after all). Ready to give up, I called Mr. Jatoi again, but he suggested that I try some more taxi stands (his desire to have me to dinner did not give up so easily!). Fortunately, I was in luck at the next stand. Mr. Jatoi spoke with the dispatcher on my phone, and they ushered me to a beat-up old car driven by a man of about seventy. He had no teeth, but a very kindly smile. The dispatcher gave him the directions that Mr. Jatoi had given them, and we were on our way. I sat in the passenger seat, a bit nervous that the gasoline gauge read “E.” As we reached the highway, and a Karachi New Year’s traffic jam, I tried to clear my mind of visions of our running out of gas by the side of the road. The driver said something to me in Urdu as we sat in traffic. I had to say, “Maaf kijiye, me Urdu nahin boltahun.” He smiled, nodded, and said “Ah.” Fortunately the traffic soon cleared, and as we arrived in a residential neighborhood, he began asking me which house it was. Of course I didn’t know, so I called Mr. Jatoi yet again and had him speak with the driver. He let me out in front of a tall building with a white tent on the yard in front. The tent was illuminated from the inside, and I could hear lively music. I walked inside, and seemed to be in a hotel lobby. There was no one there, though a large party in the tent adjacent to the lobby. I called Mr. Jatoi again (I must have called him ten or twelve times that night!), and soon he appeared, smiling, and gave me a big hug. The dinner to which I’d been invited was, it turned out, actually a wedding dinner! (I believe it was his niece who had just been married, though I could be wrong.) Immediately a servant put my bags aside and Mr. Jatoi ushered me (not very formally dressed) straight onto the dais, where I met the happy couple and many members of Mr. Jatoi’s family, including his daughter Marvi (a lawyer in Boston) and son-in-law, Awais. They were flying with their baby son back to Boston that very night! I was grateful to have them to speak to, as they were close to my age and understood a little better than most how disoriented I was feeling. They were tremendously kind and helpful to me while I was feeling pretty worn out, as by now I had traveling for twelve hours or so, with a long journey ahead. Mr. Jatoi sat me at a table with many other wedding guests, many of whom had studied in the U.S., so we chatted amiably about the differences between our countries. They were curious to hear my impressions of Pakistan, and we all enjoyed a delicious wedding banquet. I was getting nervous about the time, though (I did not want to be out during the midnight celebrations), and Mr. Jatoi arranged for his driver to take me back to the airport. I wished everyone goodbye and thanked Mr. Jatoi for his remarkable hospitality (I’ve often wondered if the married couple look back at their wedding photos and wonder who the strange mustachioed American was!). I was relieved to approach the airport in Karachi, though a little taken aback when I saw the armed guards at sentry posts by the side of the road leading to the airport (a sensible precaution, though, given the terrorist attacks there in June, 2014). Being without Emily made everything more tense for me, as I speak no Urdu, and so would be entirely dependent on the ability of everyone I met to speak English. Fortunately everyone was kind and understanding, and the trip from this point forward was uneventful. I was so happy to arrive back in the departures hall at Jinnah International Airport, though sad to be parted from Emily, and wistful about leaving this remarkable country and the myriad adventures it brings. |

Image at top left is a digital

portrait by Pakistani artist Imran Zaib, based on one of my own photographic self-portraits in Thari dress. AuthorCurious mind. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

emily s. hauze

RSS Feed

RSS Feed