|

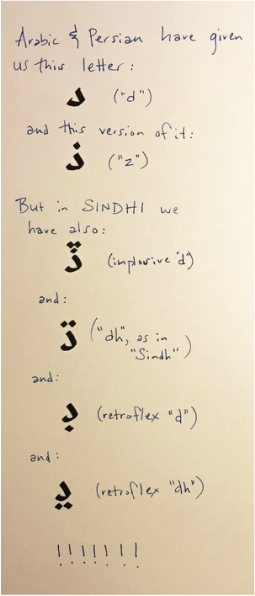

On a bright November morning during my most recent stay in Sindh, my buddies (Inam and Naz) took me to a place I had long been wanting to visit: the Sindhi Language Authority in Hyderabad. And soon I will describe all the interesting things I found there. But I also hope to convey here some sense of what I find so extraordinary about the Sindhi language, and by extension, about the Sindhi people. I am still very far away from my goal of being a true speaker of Sindhi, but I am beginning to make progress. And as I gradually learn to navigate the landscape of the language, more of the inner character and spirit of Sindh is revealing itself to me. I have been learning about Sindh for only four years, but noticed the unusually intense love among Sindhis for their language very early in that time. When I began to respond to my online friends using even the most basic Sindhi phrases of greeting or farewell, I was amazed at the fireworks of appreciation I received in return. Previously, when trying out a few Urdu phrases, I had also been greeted with surprise and joy -- but there was something different and deeper-felt in the reactions to my attempts at Sindhi. And if that was true for my online interactions, how much more emotional and delighted were the responses when I came to utter some of my practiced phrases in Sindh, in person! This can be partly explained by the rarity of the situation, since it almost never happens that any non-Sindhi (especially a white Anglo type like myself) learns Sindhi in the first place. It is also unusual for a foreigner to learn Urdu, but not nearly so astonishing, because Hindi-Urdu after all is the language of Bollywood, which is enjoyed around the world. Meanwhile, the cultural treasures of the Sindhi language have not (yet) learned to export themselves so widely. Therefore it is rare a foreigner to encounter the language by chance, and to be drawn into it enough to learn even a phrase or two. And yet, that is precisely what has happened to me--a chance encounter with a language and a culture, which has resulted in a lasting connection. I am not the first of these rare and lucky souls who discover Sindhi -- the beloved Elsa Qazi and others have already blazed the trail -- but perhaps I can help open the door for others who may similarly be enriched by it. The Sindhi love of the native language is, I believe, a contagious kind of joy, and the gentle, rolling sound of spoken Sindhi could bring a smile to even the least comprehending face. Smiling at the sounds is not enough, of course. But learning to comprehend is no easy matter. The challenge is especially great for a non-Asian like myself, who must learn the entirety of the language from the beginning, having nearly no earlier contact with any aspect of its grammar, its alphabet, its phrase structure, its vocabulary, etc.  an example I wrote up for you all. an example I wrote up for you all. But Sindhi can be a difficult language even for those who approach it from more closely related languages, especially when it comes to pronunciation. The Sindhi alphabet contains a handful of consonants that exist in almost no other world languages. These are called “implosives,” and depend on a reversal of the airflow upon production. To pronounce the implosive “dd” sound, for example, one must not only place the tongue in an unusual position at the roof of the mouth, but also create the actual sound of the “dd” consonant through a momentary in-flow of air and lowering of the glottis (which is the “implosion” implied in the phrase “implosive consonant”). If you don’t feel like trying to figure out what I meant in that peculiar description in my last sentence, I can’t blame you. Just know that it is even harder physically to create the “dd” sound than it is to understand the description of it. It is simply not something that other languages do--not even other South Asian languages. And I promise you: Sindhi people can instantly tell the difference between a correctly produced implosive consonant and an incorrect one. Every time. To date, I am not certain I have ever done it correctly. (But: I am practicing. And maybe: just maybe: I am getting close.) Learning Sindhi presents many challenges, to be sure, and not only to non-Pakistanis. Sindhi is one of dozens of languages spoken in Pakistan, and like other regional languages it must be tended and cared for in order to maintain its vibrancy and relevance. And the city that is most especially devoted to this care and maintenance of Sindhi is Hyderabad, along with its neighboring Jamshoro. For the sake of any non-Sindhi readers of this blog, allow me to share a few statistics to explain the way the Sindhi language currently fits into its landscape, and why Hyderabad is so important in this regard. It is a complex situation, because Sindh is an official province in the federal republic of Pakistan, but political and governmental realities do not always reflect the cultural identity of a place. The governmental capital city of Sindh is the colossal port city of Karachi, which is not only the largest city in all of Pakistan, but one of the largest in the world. Greater Karachi’s population is estimated around 24 million; and although Hyderabad is the second largest city of Sindh, its population of 3.5 million feels genuinely tiny compared to Karachi’s. But the differences between Sindh’s “first” and “second” cities are more significant than just their differing population size. Culturally, they are different worlds. Cosmopolitan Karachi is composed largely of transplanted communities who migrated there after the creation of Pakistan in 1947. It is not surprising, therefore, to find a substantial percentage of Urdu speakers in Karachi--roughly half of the population, according to the 1998 census*. The more surprising figure, to my mind, is that Sindhi speakers do not comprise the second-largest group in Karachi, and not even the third. Punjabi is the second largest language community in Karachi, and the third is Pashto -- the language brought to the region by immigrants from the distant northern regions Pakistan and Afghanistan. The Sindhi language, in the official capital of Sindh, is spoken by less than 8 percent of the population. This statistic in itself cracks open a window of insight on the broader issue of a sense of marginalization that the Sindhi community has felt ever since Partition. While Karachi has been rapidly expanding and transforming itself into a pan-Pakistani mega-city over the past century or so, Sindh’s second-largest city stands in greater continuity with the history of Sindh. It is not populated exclusively by Sindhi speakers, but Sindhi is by far the majority language. Hyderabad is, in essence, the cultural capital of Sindh. It is the home of the Language Authority as well as the Sindh Museum, among other things. And the cultural and intellectual nervous system of Hyderabad is further stimulated by the very close proximity of the town of Jamshoro, where the University of Sindh and the Institute of Sindhology are located. Hyderabad and Jamshoro lie facing one another on either side of the Indus, in a key position through which travelers always pass when headed either seaward towards Karachi or north towards most other parts of the country, so it is a natural hub for cultural activity.  A view of the Indus from the Jamshoro side, at the Kotri Barrage. (photo I took in Feb 2015) A view of the Indus from the Jamshoro side, at the Kotri Barrage. (photo I took in Feb 2015) The institutions of Jamshoro and and the cultural centers in the heart of Hyderabad are separate institutions (to the best of my knowledge, at least), but they share a few features in common. They are all significant, but none of them is ancient: they were founded after the formation of Pakistan. Any Sindhi person can tell you that the history of Sindh stretches back not merely fifty years, nor five hundred, but 5,000 years into the past. The challenge for the founders of Pakistan (and for its governors still today) was to find a way to link and unite a vast array of communities and cultures and languages under one flag; and a correlating challenge arose for those individual communities to maintain their own sense of self despite federation. That is a challenge faced not only by Sindhis, of course, but by most or perhaps all of those individual communities, whether they were indigenous or Mohajjir (migrated after the Partition). It would no doubt be fascinating to look at each one of those communities in depth. But Sindh is my adoptive homeland, so I am looking at this 'identity crisis,' as best I can, from a Sindhi perspective. And if I were asked to try to point to one central concept at the heart of Sindhi culture, I would say it has to do with connectedness to the living and breathing land of Sindh itself. The Sindhi language and the valley of Sindhu (the River Indus), the language and the soil, are all of one piece with the Sindhi people. The words Indus, Sindh, Hindu, Hindustan, and India all originally derive from the same root word, which is the name for the river and its valley. Though these words have grown and evolved in different directions over the centuries, I find that Sindh, Sindhu, and Sindhi all remain inextricably bound with one another as a singular concept: a place, a people, a language, an identity. To keep the language alive and vibrant is thus equal to, or at least inextricable from, the preservation of Sindhi identity. And this is the daunting challenge that has been undertaken by the Sindhi Language Authority (which I will now abbreviate as SLA). The delicate diplomacy of the task is evident in the first lines of the SLA’s constitution, which place the SLA firmly in the context of the Pakistani republic:

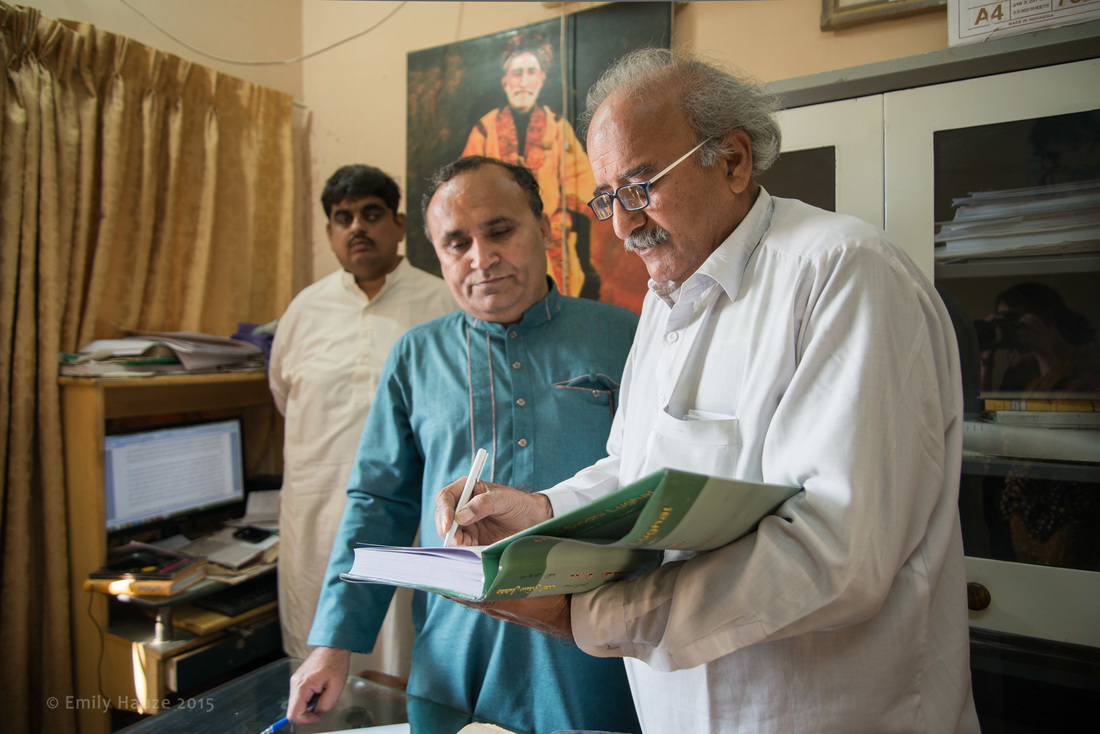

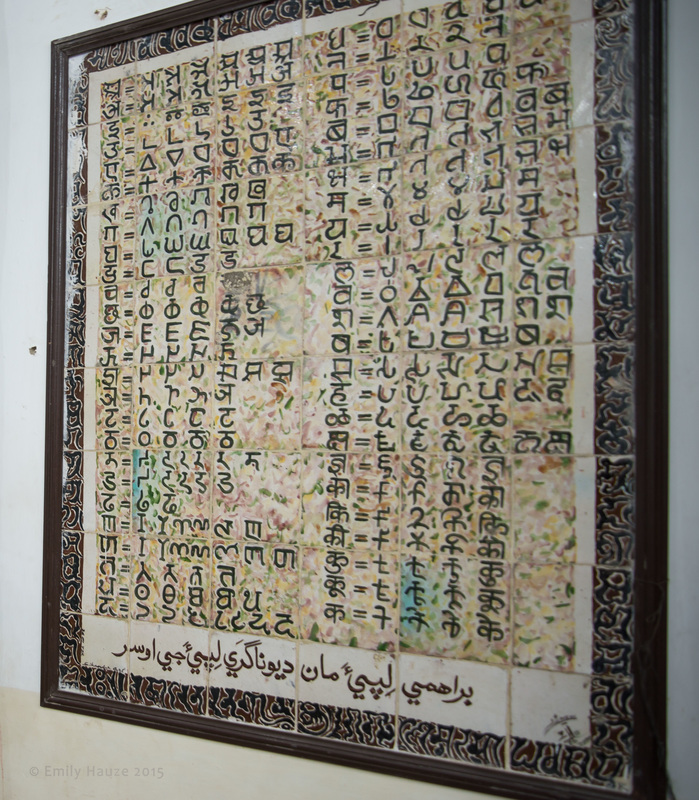

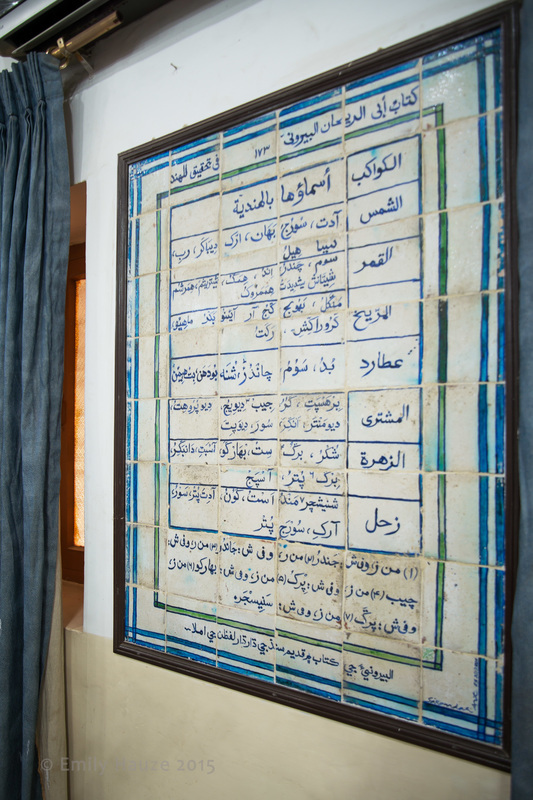

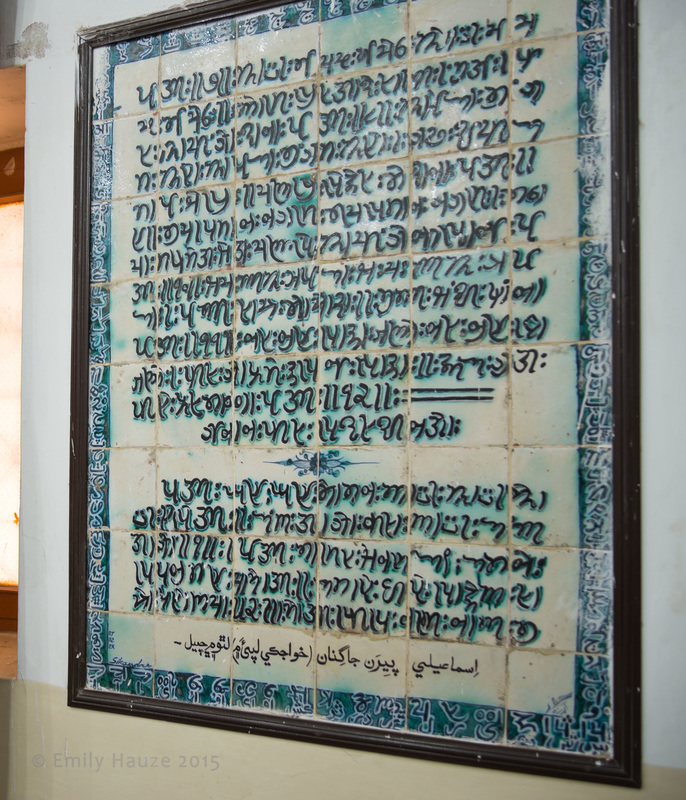

Our host, Khalid Azad. Our host, Khalid Azad. Having thus situated itself legally in the framework of the country, the SLA’s constitution then sets itself a mammoth list of duties (which can also be seen at the link above -- I will not quote them all), including the preparation and publication of reference works, oversight of the use of Sindhi in the media and periodicals, and the advancement of Sindhi computational technology. Reading through the list of responsibilities in the constitution, I was once again struck by the broad-minded role of the organization in its broader federal context. The very first item in the multi-part list of “functions” refers to promoting Sindhi in such a way as to achieve “better understanding, harmonious linguistic development, national cohesion and integration.” Further down the list, item (j) proposes arranging translations of major Sindhi works into languages such as Urdu, Pashto, and Balochi in order to “bring the National language and other Pakistani languages closer.” It is an admirable approach: the promoting one’s own (Sindhi) identity does not need to create barriers, but rather can be used to strengthen ties between groups. The next item (k) sets the SLA’s sights yet higher: “To undertake translations of major Sindhi works of scholars and writers into English for international understanding, goodwill and appreciation.” This is the function by which I am most particularly indebted to the SLA, since I am still not competent enough in Sindhi to approach the literature in its original version. These translations (especially dual and triple language editions) are an invaluable tool for me in my learning. I hope that some day my Sindhi comprehension will be strong enough that I can contribute some translations of my own towards the cause of spreading the goodwill of Sindh around the world. But now I am getting far ahead of myself. It is time to return to the story of my visit. I arrived along with my two most intrepid buddies, Inam and Naz, in the late morning. I don’t think that anyone had called ahead to alert the people of the SLA of our visit, but for people such as Inam and Naz, that kind of formality is rarely necessary. They are both well-known to all the relevant people in any place we might visit, and our hosts on these visits always feel honored to see them. And, to my great delight, I am also beginning to be a known quantity when arriving at these places -- for which I do not credit myself at all, but rather that same curiosity of Sindhi people which has sparked so much otherwise inexplicable interest in me. And so it was also on this day, as we were greeted by a smiling gentleman named Khalid Azad, who knew me right away. He had actually long been my Facebook friend, but we had had no interactions, so I think he will forgive me for not recognizing him on that day. In any case, I shall remember him now, because he gave me (and buddies) quite an extensive tour of the facility. Though the SLA building itself is not especially large, it houses a small universe of literary production facilities. Khalid Azad led us in and out of all the small offices that lined the corridors and introduced me to the various busy staff inside. The staffers seemed not to begrudge us a momentary interruption; all stood and greeted us warmly.  With a poster of the new Sindhi braille system. With a poster of the new Sindhi braille system. I think the first office we entered belonged to the couple of individuals who are working on the development of a Braille system in Sindhi. The Sindhi alphabet has 52 characters, which is cumbersome enough even for a sighted person -- twice as the English alphabet! -- and this doesn’t even include the auxiliary marks (diacritics) that denote certain short vowel sounds and other alterations to letters. To reproduce this alphabet in a coherent system to be read by the fingers instead of the eyes is no small task. In other offices we found individuals and small teams working on all imaginable aspects of textual preparation and publication. Some are working on research, others graphics and typesetting, others on archival matters, others on audio-visual material, or on periodicals, and still others on the accounts and administrative needs of the Language Authority. In one especially long, open-plan office on the second floor, we found the large team that is hard at work on the multi-volume Encyclopedia Sindhiana, the first of its kind, which will be the most comprehensive reference work on Sindhi culture and history in existence. Another major reference project underway is the “Mufasil Sindhi Lughat” -- the extended dictionary. I was pleased to be presented with the first volume of this dictionary by Mr. Taj Joyo. This first volume is already an extensive tome, though it contains only the first letter of the alphabet (alif). It is exclusively in Sindhi, of course. Receiving Vol. 1 of the "Mufasil Sindhi Lughat." Apart from the spaces where the workers of the SLA are busily engaged in their daily office tasks, the building also contains a number of spaces devoted to special uses. Unsurprisingly, there is a conference room for board meetings, and a larger hall for public lectures and events. Those things were only to be expected, but I was surprised and impressed to see the television studio, which was charmingly outfitted and seemed quite up to date. We paused here to pose for photos on the studio set, though of course we were not being recorded for any broadcast.  One of the corridors. One of the corridors. All of these various rooms, offices large and small, studios, boardrooms, et cetera, are arranged along the outward facing side of the simple and unassuming corridors. On the inward side is a pleasant courtyard in typical Sindhi fashion. The corridors stand partly open to the courtyard, as is also common in this nearly rainless land, where temperatures rarely sink to an unpleasant cold, and where the flow of the breeze gives vital relief. At first glance, these hallways could seem to belong to just about any well-kept public or official building in Sindh. There is something special about these corridors, however: they are lined with a series of tiled panels that illustrate, in text, the history of the Sindhi language. Each one of these panels is, to my eyes, a work of art as well, in elegant calligraphy of many colors. (But then, perhaps I am not the best to judge, since I am simply infatuated with Sindhi script; any common road sign in Sindh looks charming to me.) The panels do not present a straight-forward timeline elucidating the development of the language (as my Western mind might have predicted), but rather a series of windows onto different phases and uses of the language, each illuminating in its own respect, but not necessarily chain-linked to the others in a logical flow of thought. Each one is its own small treasure trove of information. For a language lover like me, these panels are infinitely fascinating. Many of them show Sindhi writing in scripts other than the one presently used in Sindh (which is, the 52-character modified Perso-Arabic alphabet that I mentioned earlier). Sindhi has connections, even living connections, with several other scripts as well. Of these, probably the most important is Devanagari, the ancient Sanskrit alphabet that is used still today in modern Hindi, Marathi, and certain other languages. Many Hindus, especially those who migrated to India at the time of Partition, use Devanagari for their Sindhi. Gurmukhi is another related but distinct alphabet used in some other Sindhi speaking communities. Hovering somewhere behind all these writing systems is the ancient pictorial writing of Moen jo Daro--those mysterious runes whose meaning has still today not been deciphered. I didn’t manage to take pictures of every panel (perhaps they are available somewhere already in a compilation, I don’t know), but here are a few of them, along with my best attempts to translate the Sindhi captions:

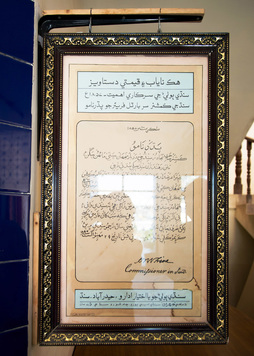

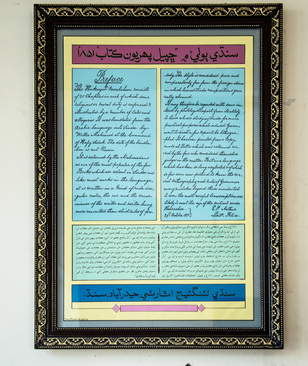

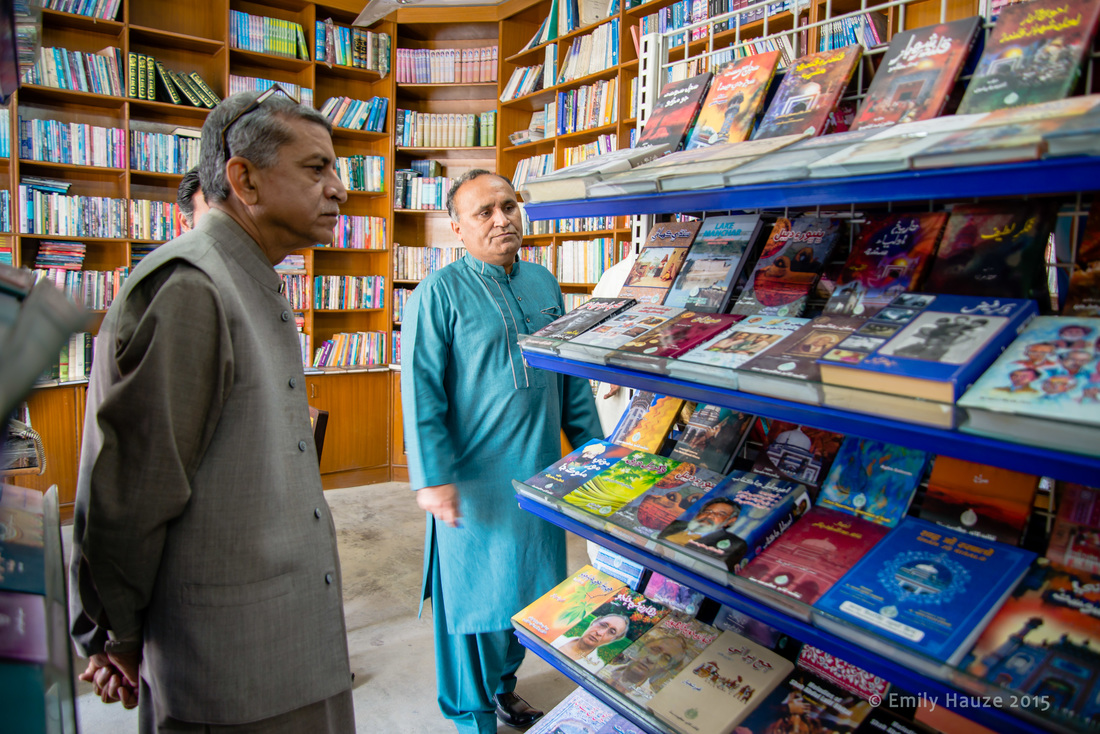

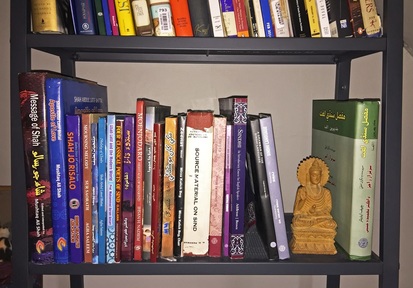

That at least offers a small peek into the visual library that is offered on the very walls of the Language Authority. The front entryway of the building is also adorned with textual significance: a quotation about Sindh from the sufi poet Rumi runs across the wall as a sort of marquee. هندیان را اصطلاح هند مدح سندیان را اصطلاح سند مدح (“Indians praise with words of India; Sindhis praise with words of Sindh"; Masnavi 2: 1757-59)  In truth, the Rumi quotation is more of an incidental mention than a keystone moment of Sindhi history. But there are a few other interesting items in that front entryway that I want to mention, which have a more direct bearing on the progress of the Sindhi language in the world. هڪ ناياب ۽ قيمتي دستاويز سنڌي ٻوليءَ جي سرڪاري اهميت. سنڌ جي ڪمشنر سر بارٽل فريئر جو پڌر نامو “A rare and precious document: A public statement recognizing Sindhi as the official language, by Sindh’s commissioner Sir Bartle Frere” If the British colonialists are remembered a bit more fondly in Sindh than they are in other parts of the subcontinent, it probably has something to do with Commissioner Henry Bartle Frere, who is remembered in the above item. Under his leadership, Sindhi replaced Persian as the governing language in the region. Commissioner Frere also required British officers in to learn Sindhi in order to facilitate work and governance.  Bartle Frere’s declaration was a rather lion-hearted one, given the ensuing challenge to the British to learn such a difficult and as-yet-unstandardized language. This second document attests to the difficulty of finding texts appropriate to help the foreign learner. It is the preface to an 1851 edition of a text which the government had selected specifically to be provided to British civil servants attempting to learn. The difficulty of the challenge is evident, for example, in these lines: “But in a language which has been so long neglected & of which so few even now pretend to know the correct Orthography and rules of Grammar many mistakes beyond those incidental to even the most careful transcription, are likely to meet the eye of the critical reader.”  The neighboring library. The neighboring library. I saw those things as we were leaving the main building of the SLA. But there was still more for me to see in the vicinity, as Naz invited me to walk to the research library next door. I was surprised to learn from Naz that the bulk of the young people we would find in the library would be those studying for the notoriously difficult Civil Service examinations. Not surprising, of course, that these students would be logging hours in libraries as they cram for the test, but surprising that there wouldn’t also be a significant number of literary students or other students of humanities making use of such a facility. But I was not able to divine a reason for this. In addition to rooms full of harried CSS students, I was also shown a beautiful children’s library in this building, decorated with whimsical murals in many colors. Returning to the main SLA building, we had one more room to visit before our tour was complete: namely, the bookshop. The shop is packed floor to ceiling with Sindhi books, and not only those published by the SLA itself, but all significant releases from other publishers as well. The majority of these books are in Sindhi, but, as I would soon see, there were some exceptions.  Receiving a treasury of books. Receiving a treasury of books. I could hear one or the other of my companions asking for books that would be of interest to an Angrez like myself, and I expected simply to be shown samples of such books to admire and then put back on the shelf. But I should have known that, in typical Sindhi fashion, these would actually be for me to keep. Bookshop staff were soon flitting about their shelves and pulling down volumes, some large and some small, until they had amassed quite a heap of crisp new books to present to me. I was thrilled to see the titles -- having to do with the history of Sindhi literature, grammar of the language, or other sundry cultural subjects. They were primarily in English, but dual-language in some cases (one of the most useful genres for the language learner). I must admit that a part of my brain was trifling with worries of how I’d be able to lift my suitcase once laden with these new gifts. But for the most part I was delighted and honored at such a beautiful gift from an organization that I admire so much. And indeed I got everything home without much trouble. Now these books have been added to my Sindhi shelf in my bedroom at home--the new additions probably nearly doubled the catalogue of my growing Sindhi library. Nowadays when I am in need of inspiration, I look to that shelf, and remember my own good fortune at having discovered a rich world of literature that had once been completely inaccessible to me. Granted, most of it is still beyond my reach. But I have been welcomed into the lap of this language, and daily more of its mysteries are being revealed to me. It will take me months and years to learn it comprehensively. But that is my goal -- and I am grateful to the Sindhi Language Authority, for helping to make this possible for journeying souls like myself from around the world. Additional photographs from the Sindhi Language Authority and neighboring library:

16 Comments

3/4/2016 07:42:33 am

Emily, I really enjoyed reading your blog. You are truly an ambassador of Sindhi culture and language. God bless.

Reply

Emily

3/5/2016 06:27:52 am

Thank you so much dear.

Reply

faraz

3/4/2016 07:50:34 am

emily dear, i read your blog about SLA it was full of knowledge full pictures, i had never visited SLA even though i lived near to SLA buliding from last couple of years but after reading this blog. i am thinking to visit this place and hope i will visit soon.

Reply

Emily

3/5/2016 06:28:23 am

Very grateful dear!

Reply

Bashir Abbasi

3/4/2016 07:58:59 am

Superb explanation of Sindhi language, and the spirit for learning Sindhi language you have shown is unprecedented. I appreciate your efforts, love and joy to learn a foreign language and culture is really amazing.

Reply

Emily

3/5/2016 06:29:13 am

meharbani!

Reply

Hameed Kazi.

3/4/2016 05:47:52 pm

A beautiful attempt and very extesive work done by you Emily for Sindh and Sindhi language. Congratulatios to Sindhi language Authority as well for doing such good work. Your love for Sindh and Sindhi is fascinating. Thanks vey Emily. Keep it up and God bless you. Only one correction. The Photo of Kotri Barrage shows the down stream side of Barrage. Jamshoro is on the right hand side . the far end - and not the end you say.

Reply

Emily

3/5/2016 06:32:07 am

Thank you very much, dear Hameed!

Reply

NazSahito

3/5/2016 04:41:27 am

this is totally adifferent piece of writting ,with scholarly research and love for land ,people and lnguage of Sindh.you have done really a great job by communicating that Sindh is a different soil in sub continent,,,,i here quote your two short paragraphs,which are enough to narrate the ground realities and your feelings,,,,,,,,,,,,,The sindhi language ,in official capital of Sindh , is spoken by less than 8percent population.This Static itself cracks open a window of insight ,the broader issue of sense of marginalisazation , that the Sindhi community has felt ever since partition,,,,,,,,,2,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,I hope that some daymy Sindhi comprehension will be strong enough that i can contribute some translations ofmy own ,towards cause of spreading good will of Sindh around the world........I think you haver done a great service to land ,which you have adopted as your home .Here we are always available to welcome you , in our homes and in our hearts.

Reply

Emily

3/5/2016 06:33:07 am

So grateful, dear Naz -- for your close reading of the blog, and for your guiding presence and sunny friendship. :)

Reply

Danish Latif Nizamani

3/5/2016 08:37:21 am

Nice piece of writing..stay blessed Emily Hauze

Reply

Rafique Memon

3/7/2016 10:59:33 am

Emily, I have gone through ur blog. This is amazingly an accurate analysis of a foreigner who adopted Sindh as her second home. I congratulate you on this work and want to encourage you to work on the aspect of efforts by the Sons of Soil to make Sindhi a part of modern family of languages. This particularly refers to launching of Sindhi satellite TV channels , computerized composition in Sindhi and very recently, inclusion of Sindhi in the translation system of Google, Thanx for being a true Sindhi dear...

Reply

3/9/2016 11:09:53 am

It was a real pleasure to read your blog (and watch the photographs) regarding your visit yo Sindhi Language authority @ Hydearabad. I might have visited it a dozen times but still found it informative and interesting. You have narrated your observations wonderfully well. I found some of your observations particularly touching and true, as this one.

Reply

Uzair soomro

3/12/2016 08:31:41 am

You r very Good work Of sindh

Reply

Ranjit Ajwani

12/4/2018 07:06:36 am

Enjoyed reading your blog it was very informative and interesting and the way you have quoted the written,

Reply

10/17/2022 12:11:53 am

Rock business successful. Career decide father.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Image at top left is a digital

portrait by Pakistani artist Imran Zaib, based on one of my own photographic self-portraits in Thari dress. AuthorCurious mind. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

emily s. hauze

RSS Feed

RSS Feed