|

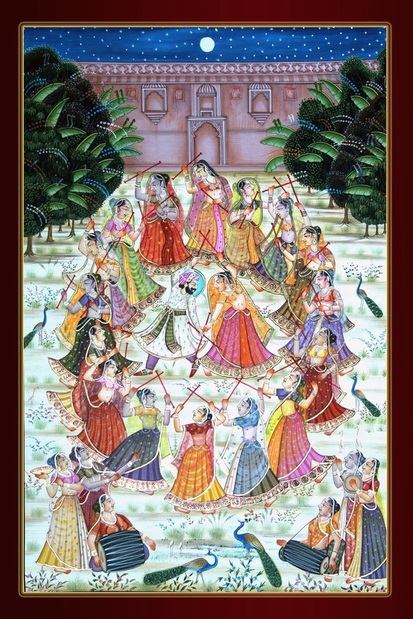

What happened to the Dancing Girl? It's a question within a question and a story within a story -- because actually there are two dancing girls. One of them is Sambara, from the Indus River Valley of 5000 years ago, immortalized in the shape of a small figurine. The other is me. The stories are multiple and interconnected: what happened to her, what happened to me, and how we came together. But before I can explain what happened to this dancer -- me -- I must ask a broader question: what happened to dance itself in my culture? Which is to say, white American Protestant (Christian) culture. I won't be so dramatic as to say that we have lost dance, but we have hidden it--pushed it into the shadows, ignored it, and all but forgotten it in our daily lives. Dance, for us stereotypically repressed Protestants, is something can happen only within very specific arenas, and at very specific times. It can happen on stage, in the context of a young girl's ballet recital or a musical number in a Broadway show. Or it can happen in fraternity-style parties, formless and frenetic, typically requiring a fair amount of alcohol to loosen the inhibitions of self-conscious partiers. And even in these sanctioned situations, actual dancing tends to involve a lot of timidity and trepidation. On the whole, dance is something that makes us nervous.  Me, age 5. 'dancing age.' Me, age 5. 'dancing age.' Children do not have this inhibition against dance. I can remember a phase in my own early childhood in which I demanded that I be dressed in skirts every day so that I could twirl and bop around to my heart's content. And like many of my peers I went to ballet classes and enjoyed the stylized movements and the opportunity to perform in the yearly recital. But that childhood freedom to dance soon met with the challenges and hindrances of adolescence. As the young ballerina grows into an anxious teenager, she tends to stop going to ballet classes and try to blend in with her peers. (Here I am abstracting my own experience into the third person, but the following sketch is essentially autobiographical.) The graceful gliding of ballet would stand out painfully among the brooding adolescents, so she intentionally forgets the dancer's way of thinking. She gets to relive the excitement of choreography in a very contained way if she participates in any musical theater -- opportunities for which are relatively abundant in high school and college but dwindle sharply after that. The college girl exchanges theater dancing for the occasional awkward twisting and jiggling on the frat-party dance floor, and then, after graduation, all but abandons the entire notion of dance for the years to come. If the girl is not interested in "clubbing" (as I am not), dancing then only re-emerges at weddings, where it takes essentially the same form as it did back at the frat parties, with all the associated discomforts and intoxications.  Edgar Degas: "Petite danseuse de quatorze ans," c. 1879. Edgar Degas: "Petite danseuse de quatorze ans," c. 1879. The French Impressionist Edgar Degas is known for his paintings and sculptures of young ballet dancers--all of whom are just shy of that age when dance becomes uncomfortable. His bronze statue of a "little fourteen-year-old dancer" is already teetering on the edge of maturity, however, and all its associated anxieties. Her feet gracefully mark a carefully learned ballet position, but her shoulders slope backwards uncertainly, and her face--well, perhaps it is simply a dreamy or absent expression, but to me it appears to bear a shadow of the kind of anxieties that teen years are certain to bring. This is not an academically researched hypothesis, but what I am seeing in Degas is a fascination with dancers precisely at this turning point that I can recall in my own life--the moment in which dancing goes from being routine, comfortable, natural, to being self-conscious and inhibited. It would not be fair to say that we have done away with dance entirely. We have an idea of dance, even an ideal of what it should be -- but we rarely embody it. [I have not yet done any research on this topic, but I expect there are probably scores of books about the uncomfortable relationship that my cultural compatriots have with dance. If anyone reading this post would like to suggest any good articles for me, please do comment!] I can't even say that dance is stigmatized -- because I don't think that this ever happens on a conscious level. We don't actually dislike dance. But still we don't do it. Or, we do it so rarely that it seems alien to us when it finally becomes time to dance. At some point--and probably that point is adolescence--we un-learn dance. In recent years a few things have made me particularly aware of the alienation of dance within my native culture. I will cite here two examples. The first is Bollywood cinema, in which dance is not only present but essential. One especially vivid instance is a scene in the movie Lagaan, in which a whole village, plagued by drought, falls into the sway of a rain dance. The scene is intricately filmed and must have been a huge undertaking from the perspective of cinematography and choreography. But what makes it so touching is actually its simplicity. The villagers -- people of all ages, shapes, and sizes -- dance with a natural rhythm that seems no more difficult than walking. To my Western eyes, it seems as if all these people, when they were children, had not only learned to crawl and then walk, but then advanced just one more phase into a basic and perfectly self-evident form of dance. Each person has his own personality and ability--just the way a person's walking gait is always individual--but the basic movements of the dance remain consistent throughout the whole group. The music, a translucent and minimalistic piece by A. R. Rahman, underscores the sense of unity. The texture of the music is almost nothing more than what is needed to dance with. It is a structure and a surface on which a whole village can dance, with a single melody that is passed seamlessly among the characters, like a colored ribbon weaving its way around the scene. Musical numbers within Western theater and films, when it is done well, can have a similar kind of effervescence--but it is very rare to find an example of group dancing in Western that feels so uninhibited and natural. The Lagaan rain dance, despite all the glorious artifice that must have been required to coordinate it, seems to spring forth from a source deep within the people themselves.  Picasso, "La Ronde de la jeunesse," 1961. Picasso, "La Ronde de la jeunesse," 1961. My second example is one closer to my own home. Growing up where I did, I might have easily assumed that dance was a rather distant phenomenon for all Americans--but I would have been mistaken. Outside of mainstream white Protestant America, dance is much more vibrant and alive. I came to see this quite distinctly when my husband and I attended a Jewish wedding for the first time--a couple years ago. Andrew and I had both enjoyed the musicality of the ceremony, which involved a lot of traditional chanting in Hebrew. To our amazement, the entire (Jewish portion of) the congregation knew, without any written cues, what to sing and when to sing. But we were stunned when, a short time after the ceremony, the married couple was presented to the assembled guests at the reception, and the Hora was announced. We were both vaguely familiar with the word "Hora" (a traditional Jewish circle dance) and we recognized the tune that was struck up by the wedding band. But we were amazed by the sudden energy that transformed the crowd in this moment. Within seconds this scattered bunch of people took on a shape and a trajectory and a thrilling energy. We ourselves were soon swept up into these concentric circles and revolving with the others. Andrew and I were quickly separated by the dance (I think the circles may have been gender-segregated) and found ourselves holding hands with strangers--and feeling completely welcomed by them. We mimicked their steps as best we could--which was not very well--but it didn't matter that we were new to it. We had a marvelous time. Driving back home that night we kept repeating our amazement to one another that a group dance like that could feel so warm and fun and uninhibited. And we kept asking -- why didn't we grow up with this kind of dancing, too?  Original Sambara. Original Sambara. But now I must interrupt my own reminiscences to introduce the original Dancing Girl -- Sambara of Moenjo-Daro. We know her as a bronze figurine, only 10 cm tall, and 5,000 years old. Her original stands in a museum in New Delhi, but her replicas are scattered widely about her home province of Sindh, and one of them now adorns the 'Indus Valley shelf' of my display cabinet. Along with several other iconic relics, the Dancing Now, it is not absolutely certain that Sambara (the name with which my Sindhi friends refer to her) is actually dancing. And she may not just be a 'girl who dances' but rather a "dancing girl" in the figurative sense. (Incidentally I was only a bit surprised to see that the original statuette is rather more anatomically detailed than my replica version, which has been ever so slightly censored. The original Sambara bears her body with no inhibition whatsoever.) But whether or not she is actually dancing, Sambara seems to embody the spirit of dance. Her long arms are positioned with striking confidence, and her legs seem to be bending to a beat. Her left arm is fully decorated with bangles of the sort that the women of the Thar desert still wear even today, and which I myself have had the honor of receiving (see my portrait at the top of this page). Indeed, those bangles constitute the majority of her clothing. Her state of undress, however, is less important than her attitude of confidence. Whatever it is she is doing, we can sense that she is doing it without inhibition. She is displaying herself, and she is comfortable with that. That bodily self-confidence is the main difference, to my eyes, between Sambara and Degas's bronze dancer. Both girls have thoughtful faces, but the thoughts are quite different. Sambara is thinking about her dance--she appears ready to dance, indeed, seems already moving. But what about Degas's danseuse? Her feet are in position, as if on instinct. But her sloped shoulders and absently upturned face suggest that her mind is somewhere else completely. She is thinking about everything in her life that isn't dance. She is growing and becoming an adolescent and adapting to the changing world around her. And this is not a bad thing. She is becoming introspective -- she may be developing a complex and beautiful personality. But at the same time: she is getting ready to abandon the dance shoes for something more practical. She is moving away from the dance floor. She is beginning to unlearn her dance. Sambara might also develop a complex personality that involves a lot more than just dancing. She does not look like a simple-minded girl. But the difference is that I do not see her giving up her dance as she continues with her life. Dancing will simply be a part of her life. Like it is for the villagers in Lagaan, dancing is just a breath away from walking. Just another natural state of being.  Me rehearsing with my kathak class. Me rehearsing with my kathak class. Now, I don't mean to bemoan the lack of dance in my life for the last couple of decades too dramatically. Because all is not lost. Dance does not play as large a role in my native culture as I wish it did -- but opportunities for dancing do exist, and I am taking advantage of them. I have not returned to the dance form of my childhood (ballet), but instead to a different classical dance -- kathak, which originates in northern India. It is my good fortune that we have here a wonderful teacher of kathak from Calcutta, Pallabi Chakravorty. I had taken her class briefly as a college student, but at the time did not devote enough of my consciousness toward absorbing it. But I must have tucked my interest in kathak away somewhere in my mind, because recently I felt the urge to try it again. And fortunately Pallabi allowed me to rejoin the class.  Holi circle dance; painting serving as basis for our kathak performance. Holi circle dance; painting serving as basis for our kathak performance. It has been a very long hiatus for me: twenty years. I left dance in my pre-adolescence at age 11, and have returned to it at age 31. It is a welcome return for me. Kathak is a fascinating dance form and deserves a separate post of its own -- so I will save that for another date (soon, I hope). For the moment, I will just say that learning about kathak has not only reconnected me with my inner drive to dance, but has also given me another window onto my adoptive (south Asian) culture. The piece that our class is preparing for our spring recital is based on traditional Hindu themes, specifically Krishna and his Gopinis (his young female adorers), and the springtime festival of Holi. Our piece concludes with a circle dance of the sort associated with Krishna and Holi. It feels especially meaningful to do a circle dance, as this resonates with the joyous Hora and many other archetypical ideas of the communal experience of dance (such as the Picasso image above, a print of which hung on the walls of my childhood home, or Matisse's iconic painting entitled simply "La Danse"). So: the dancer within me has been rediscovered. The last part of this story is the "rediscovery" of Sambara. By which I mean: the way in which Sambara has made her way into my home. She is of course a native of Moenjo Daro, and thus shares her homeland with my adoptive Sindhi family, the Sangis. So when my adorable Sindhi papa Saeed was planning a surprise package of gifts to send me, he wanted to include a replica of Sambara. That package, however, was stopped at customs in Dubai, where an over-zealous security person confiscated it, thinking it might be an original. (Clearly he was not familiar with the anatomy of the original Sambara.) The box that arrived on my doorstep contained many other Sindhi treasures, but no Dancing Girl. When papa Saeed discovered the issue he rapidly devised another surprise plan. He packed up another Sambara replica among yet another set of delightful Sindhi treasures (clothes and jewelry) and asked his friend, who was heading to a conference in Washington, D.C., to pack them in his luggage. His friend kindly mailed them to me from there, thus avoiding the problem of misguided customs officials. Just last week this surprise package arrived on my porch. And now my own Sindhi Sambara lives in my display cupboard, along with my other Moenjo Daro souvenirs (see my earlier post "Sindh" for a pic of those). And, I think, she has arrived at the perfect time.

8 Comments

SAEED SANGI

4/6/2014 01:49:36 pm

GREAT STORY , NARRATED BEAUTIFULLY. DANCE WILL NEVER DIE. IT STILL SURVIVES IN SINDH IN THE FORM OF JHUMIR(NOT LIKE SAMBARA BUT FULLY DRESSED IN COLOURFUL TRADITIONAL ATTIRE). DURING MARRIAGE CEREMONIES OR OTHER HAPPY OCCASIONS AND EVEN CULTURAL NIGHTS. HO JAMALO IS ONE MUSICAL DANCE IN WHICH EVERYBODY PARTICIPATES EVEN THE CHIEF GUEST AND HOST. A REALLY TREAT TO WATCH.

Reply

Emily

4/8/2014 01:41:47 am

thanks for the wonderful comment, papa, and for being a part of my return to the life of dance :)

Reply

4/7/2014 03:18:10 pm

Great post. I am really impressed that you've resumed dance and you associate that much meaning with it in life. I have more to say on it later. Now in haste. :)

Reply

Emily

4/8/2014 01:42:28 am

Thanks so much, Zaffy! I look forward to hearing your further comments... which you can put on the FB thread if you prefer, for easier dialogue... https://www.facebook.com/emily.hauze/posts/10201251450040827

Reply

Gul Agha

4/8/2014 06:51:20 am

Dance, when you're broken open.

Reply

Emily

4/8/2014 12:54:36 pm

Wise words.

Reply

Aziz Mehranvi

5/2/2014 05:45:24 am

Let your renown make the world of dance known!

Reply

Emily

5/2/2014 10:06:04 am

Thank you so much, dear Aziz, for your kind and heart-touching comment.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Image at top left is a digital

portrait by Pakistani artist Imran Zaib, based on one of my own photographic self-portraits in Thari dress. AuthorCurious mind. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

emily s. hauze

RSS Feed

RSS Feed