|

My night in Thar had ended in music, and so too did the next day begin. After breakfast in Irfan’s office (at which I was most pleased to see that delicious makan’u-maaki once again), we were introduced to a young man named Zawar Hussain, who, we were told, is a “rising star of Sindh.” I didn’t know what was meant by that until, moments later, he burst into song. He is a slim young lad whose physical presence takes up very little space, but his voice is strong and easily could fill much larger rooms than the one we were in. Although most of the Sindhi poetry he was singing is still far beyond my level of understanding, I was able to recognize the text as Shah Latif’s tale of Sassui and Punhoon. The legend has it that the Baloch prince Punhoon had traveled all the way to Bhambore in Sindh to see Sassui, so renowned was she for her beauty. The two fell in love and were married; but this angered Punhoon’s brothers so much that they drugged him and dragged him back to Balochistan on camels. The song of Sassui is, therefore, one of grief and longing, as she sets out on her own to follow him across the desert. She is willing to face all the blistering hardships of the terrain in order to seek her beloved. And this is what Zawar Hussain sang to us that morning:

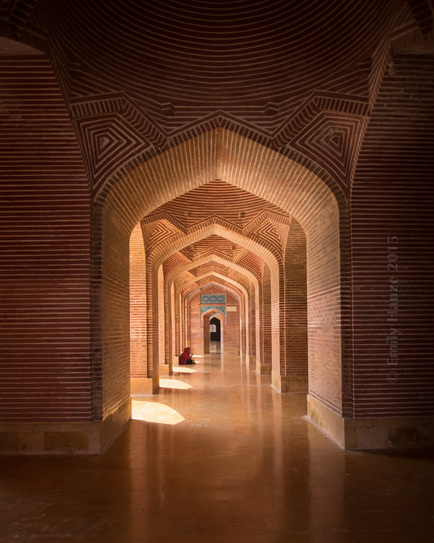

And Zawar’s song sets the tone for what follows. Soon after this performance, my buddies and I set out to visit a village where the means of living have changed very little in the centuries since the Sassui of Latif's tale set out on her journey.  Children's program in progress Children's program in progress But -- first I would like to step out of order here to recount one other story from Radio Mithi, which actually took place after our breakfast but before hearing Zawar’s song. As Mustafa (Irfan’s chef) cleared away our breakfast dishes, Irfan mentioned that there was a children’s program currently live on air, and would I like to see it? And of course I was eager to see it. So we left his office and crossed the now-familiar small and sunny courtyard to the production side of the radio building. A small thicket of child-sized shoes had covered the floor right outside the studio door, to which we (Irfan and I) dutifully added our own shoes, and then attempted to enter the studio as quietly as possible so as not to disturb the program in progress. But surely it must have been a great distraction to the children and the program host to see the station director enter their space along with a clearly foreign female guest. But, like the dauntless radio reader the previous day, the present crowd also kept their focus admirably -- at least the ones who were currently speaking into the microphone. The younger children on the periphery did turn their large eyes to us to stare with an expressionless curiosity. Irfan and I sat down on the floor, where about a dozen children were gathered around a pair of microphones. A man sat at one of the mics, interviewing a boy seated at the other. Irfan waited until they had reached a pause, and then borrowed the presenter’s mic. Irfan spoke in Sindhi, which the children there must have been able to understand, though I think they were primarily Dhatki speakers. And I could not understand everything that Irfan said, but I understood when he asked the boy at the other mic, “I heard you say before that English (Angrezi) was your favorite subject in school, is that right?” “Yes,” said the unsuspecting boy. “That’s great,” continued Irfan. “But have you ever met a real Angrez in person before?” (In South Asian parlance, any native English speaker counts as being “English,” including Americans. Being a lifelong Anglophile, I love being referred to in this way as an “Englishwoman.”) The boy shook his head in an innocent ‘no.’ “Well, now you have,” said Irfan (still speaking in Sindhi). “My guest, Ms Emily, comes from America.” And he handed the microphone to me. I said a few words about how lovely it was to be visiting Mithi. I tried to keep my language very simple, though probably it was still too much for most of the children listening to the program. Nonetheless, I suspect that our young fellow who loves English class at school was able to understand a bit of it.  Zawar Hussain, Khatau Jani, and me. Zawar Hussain, Khatau Jani, and me. Then I handed back the microphone to the regular presenter, and we let them all continue with their show as we slipped out again, as quietly as we could. We returned then to Irfan’s office, which is where young Zawar Hussain was waiting patiently to sing for us -- but I have already narrated that part. After we applauded Zawar and bade him farewell, we set out again for a village. We were going this time to the village of Mustafa, the chef. We took two cars now -- Mustafa and Hanif (Irfan’s driver) led the way in one car, and Irfan drove the rest of us (me, Naz, Khatau Jani) along behind. The sand of the desert is a bright white in the noon-time sun. This is my least favorite time of day for photography -- when everything is awash with too much light, and colors tend to lose themselves in the glare, and eyes wrinkle up into squinting expressions or are lost behind dark sunglasses. But I was fortunate to be visiting in the cool of November, when only light is a problem, and not heat. The November sun, for all its brightness, is mild in its temperature. I can only imagine what that glare must feel like in the stinging summers. It was only a short ride to Mustafa’s village, and we parked our cars on a stretch of white road that was almost indistinguishable from the gleaming sand around it. A pair of young girls who were standing there looked up at us with forlorn expressions as we got out of the car. Yesterday’s village had been tucked into the side of a sand dune and had appeared to us out of that misty sunset as if from a dream. Mustafa’s village, by contrast, was set mundanely on more even ground, and the clay walls and mud roofs felt perfectly solid as they stood fending off the beating sun. There was far more trash on the ground, gathered in heaps and scattered all about the sandy earth. Trash collection is lacking even in urban areas of Sindh--so what are desert villagers expected to do with it all? It can hardly be surprising that wrappers and plastic trimmings of modern consumerism, having reached the village, have proceeded to pollute it.  Mustafa at the edge of his village. Mustafa at the edge of his village. There were no peacocks wandering in the shadows. There weren’t as many sources of color anywhere--not as many bold and beautiful rillies, not as many women draped in queenly colors. I might have thought that the comparatively muted colors were the result of my faulty memory, but my photographs seem to confirm it. I, in my hot-pink dress, was far more brightly dressed than the village women. However, many of the women I would soon meet did not wish to be photographed, so the photographic record can’t represent the full range of what I saw that day. Irfan told me that Mustafa’s female relatives had wished to meet me, so I should walk with him towards the nearby cluster of huts. My buddies, being male, were not invited, but they would be nearby, visiting with the village menfolk. So I followed Mustafa across the sandy terrain and asked him a few questions. He could speak only a very tiny amount of English, but we managed to communicate in a mixture of Sindhi and Urdu. He told me that his sister and his mother especially were excited to meet me. I asked if he had learned to cook here in the village. He said yes, but was eager to tell me that cooking was not his only profession: he had also worked as a photographer and a makeup artist. I was impressed that he had found opportunities like this that brought him out of the village -- he had found work with some sort of a broadcasting company in a major city, perhaps Hyderabad -- though I wasn’t able to catch all the details. We crossed into a sunny courtyard, where a few children were wandering at the edges, and a few small and sleepy-looking goats were resting. It seemed very quiet and still -- perhaps many villagers were indoors avoiding the bright midday sun. But after a few minutes some more women and children started to emerge, and Mustafa pointed to his sister, who was carrying a very young child. She approached and greeted me warmly. She was a very short woman of a rounded figure, and she seemed to be of an indeterminate age. Her appearance seemed much older than her brother -- and I could not tell if this was the result of years or of the difficulty of her lifestyle in the village. One of her eyes gazed at me clearly and solidly, but the other seemed enlarged and discolored, perhaps the result of some childhood disease,. The child she was carrying, though only a toddler, seemed quite large against her squat frame, and it seemed to me he would be quite heavy in her arms. But she was also spirited and strong, despite those other visible signs of hardship. Soon I also met her mother, who appeared in the doorway of one of the huts. To my eyes she looked almost identical to the daughter - only a little bit farther along on the path of time and aging, but not so very much farther. This led me to wonder whether perhaps the hardships of poverty are weighted unexpectedly early in life, causing women to age more quickly in early years. And perhaps that is the case in any situation where childhood is so promptly followed by -- or in some cases even overlaps with -- childbearing.  Tea and a khatta to sit on. Tea and a khatta to sit on. I was invited into one of the houses, which was in this case not one of the round huts, but a rectangular and more spacious one, built of the same smooth-edged mud clay material. There was very little inside it apart from two khattas (four-legged cots with woven surfaces for sitting or lying on). I was urged to make myself comfortable on the khattas, while Mustafa’s sister sat on the other with her child, and Mustafa remained standing. My eyes adjusted to the dimness inside the house, which was a stark contrast to the flooding sunlight just outside the door. I was asked if I would take some tea--to which I naturally said yes. Mustafa’s sister was talking -- partly to him, and partly to me, though I sadly wasn’t able to understand much of anything at all. I am not even sure at this point whether she was speaking Sindhi or Dhatki; if it was Sindhi, then it was in a local accent that my mind could not penetrate. Without understanding the words, I could nonetheless perceive a certain intelligence and clarity in the way she was expressing herself. I wished that I could leap forward several years in my language learning to be able to connect with her in some real way.  As it was, I caught only a few words and ideas -- particularly the word “ghareebi” (poverty), which she said more than once. “We are very poor people,” she told me. I wasn’t sure if she was telling me this out of self-consciousness, or perhaps some degree of embarrassment at the comparison to myself coming from visible privilege, or to gain sympathy, or for some other reason entirely. But I felt all of these things on her behalf, upon hearing her speak. I responded rather helplessly--and probably in English--that they were nonetheless rich in spirit and hospitality. By this point I had been presented with a cup of hot and milky tea, which was as delicious there in the village as it is anywhere else. Sindhi hospitality is a theme throughout this blog--in a way, all of this writing is an ode to Sindhi hospitality--and this is a quality that is common to all the people who have welcomed me into their homes and lives during my travels. Guests are always honored in Sindhi culture, even among people who have almost no possessions to call their own. I felt this as I sat in perfect comfort on the khatta in the shady house, drinking sweetened milky tea, protected against all the hardships of life that these villagers face each day. Because the others were out and about -- working, hauling water from wells, herding their livestock, tending their children. Theirs is not a life of idle tea-drinking on comfortable cots. But for a guest, they will always take time and care to make a comfortable space for visiting, which is an honor indeed. Mustafa had taken my camera into his hands and was snapping pictures of me there with my tea. The results are mostly not in good focus or properly exposed, but that is only the result of my not being able to communicate to him well enough how to use the settings on my camera (he does have, after all, some experience in photography--just not with my camera model). And he held on to the camera as we went back outside, instructing me to go and pose in front of this or that hut while he took pics. I knelt down to stroke a small goat who was loitering about in the courtyard. Anyone who knows me knows my curiously intense love of goats -- somehow I can’t resist them, with their blunt round heads and rambunctious energy. I love the simple joyfulness in the way they prance about butt into things, and their complete lack of shyness, and the way they try to munch harmlessly on anything they can find. I could happily spend hours in the presence of goats. I seek them out here in America, too, but they are harder to find here. You have to go visit distant rural farms and petting zoos to find a goat. In Sindh, however, goats and goatherds can be found anywhere, even in cities. But they are a part of the fabric of life in villages especially, and their hardy gentleness fits most naturally into this context. Some of the village children were watching from a slight distance and saw me smiling at this small goat. One of the children picked up another, even smaller goat, and brought it to me. I sat down on the ground so that I could take the little goat into my lap. Mustafa seemed worried for a moment, and said, “na Adee, tawhaanja kapra kharaab theenda!” (No sister, your clothes will get dirty.) “Na na, mushkil konahey,” I managed to respond (‘no no, it’s no problem’), trying to convey that a bit of dirt on my clothes was a small price to pay for the innocent joy of holding a goat, in my opinion.  Where the menfolk had gathered. Where the menfolk had gathered. The children seemed delighted -- though certainly not more delighted than I was -- and one by one they kept bringing me more small animals to play with. Mustafa still had my camera and took some more pictures as all this happened, there on the smooth clay floor of the sunny courtyard. The warmth in the children’s smiles and giggles as they brought me their animals is probably my sweetest memory from Thar. And I would have happily stayed there with those children and their goats and lambs for hours, if there had been no time constraints. But the day was advancing, and the time had come for me to rejoin my buddies. So I walked with Mustafa down a lane and then across a sandy passage to where the menfolk were gathered. They were outside as well, in another courtyard, where there were three cots arranged in a U-configuration. This area was a little bit shadier due to its proximity to various spindly desert trees and high shrubs. And a charming gathering it was -- several generations of men and boys were clustered around my buddies. As I approached, the small crowd parted for me, clearing off one of the cots completely so that I could sit on it undisturbed. The fellows who were thus displaced moved instead around the edges of the gathering and stood while I took my place on the cot. Though I certainly didn’t need all that room to myself, I did appreciate their courtesy. A lady can always expect such courtesies in Sindh, I have found -- especially as an honored guest. Occasionally I have been asked if I had ever felt threatened or preyed upon by men during my travels, and I’m happy to respond that no such thing has ever happened to me, and that my presence and person have been given more respect and honor in Pakistan than anywhere else I’ve been. And that this courtesy is the same among all classes--whether I am in a village or among intellectuals or in the presence of some high official or other. In any event, we did not linger very long in that setting, with the three khattas and the sun and dappled shade. But we stayed long enough for Irfan to introduce me to one of the oldest gentlemen gathered there. “He has been telling me,” said Irfan, “about how much he loves to listen to the radio. He listens to my station, of course, but he also tunes in regularly to the BBC Urdu Service. He has been a loyal listener for decades. Look, he brought out his radio to show us.” The elderly gentleman lifted his machine onto his lap -- a sturdy metal box of an older vintage such that I haven’t seen in many years. This was a radio from the days before cheap electronic displays, from the analogue days, when you would turn a smooth dial to navigate across the radio spectrum, across seas of static onto small islands of active signal. This radio has been working for decades, keeping its owner connected to the broader world (the BBC! the same radio service that keeps me connected to the world every day). And somehow this steadfast machine has continued to capture those signals, despite lost knobs and warped metal and decades of desert sand threatening to grind down its inner workings. That old gentleman must have thousands of fascinating stories to tell from his own life -- for a man who listens is one who perceives -- but unfortunately I was not able to stay and hear any of them. It was already time for us to be leaving. We were expected back in Hyderabad by early evening, and we had a long road journey ahead of us. So we said our farewells to Mustafa and his fellow villagers. Among the children who had gathered near us in those last moments were the two girls who had been standing there by the car when we arrived, and whose faces had struck me as forlorn. But in the whirlwind of new sights, I had not noticed that these were the same two girls -- but fortunately my camera has preserved them so that I can make the connection. First impressions are often deceptive: those faces that had seemed rather blank and lost now seemed calm, curious, radiant. Their lives are difficult, no doubt, and they live under a constant strain of poverty -- but you cannot fail to see the grace and depth of their spirit when you spend even a small amount of time with them. I would have loved to spend much more time at their side.  Interior of Naukot Fort. Interior of Naukot Fort. But as it was, we climbed back into our two vehicles, which proceeded to grind their way back out on the sandy roads. When we reached the edge of Mithi, we got out and said goodbye to Khatau Jani, who then headed back to his normal life in his small and beautiful city. And our driver, Hanif, once again took the wheel, while I sat in the front seat, with Naz and Irfan in the back. And the four of us were on our way out of the desert, soon to leave that strange and wonderful place, with its peacocks and its prickly shrubs and ancient radios. But we took a different route this time -- not the new commuter road that had carried us so smoothly before, but another, rockier one, which led us to a different exit of the desert. But before that exit, just inside the desert gates, there was an old fort, Naukot, which was our reason to take this route. Naukot has a similar design to other Sindhi forts I have visited (Kot Diji and Ranikot), with vast mud-brick battlements, and rounded towers. Of those three, Naukot is the newest -- only 200 years old, compared to Kot Diji’s 250, and and Ranikot’s exact age is unknown. It was built by one of the Talpur emperors, Mir Karam Ali Khan Talpur, in 1814. This same Talpur is also the one who built and is buried in the Hyderabad tombs, which I wrote about in an earlier entry. And our same buddy, Ishtiaq Ansari, who oversaw the beautiful restoration of those tombs is now also heading the effort to repair and renovate Naukot Fort. Our visit there was a short one, however--owing in part to my own travel-saturated exhaustion. We drove right inside high gate in our car--a gate that would be more naturally traversed on camel-back, or even better, on an elephant. But we drove right in. And we saw the sights, climbed the ramparts, took some pictures. It was a brief but interesting stop, worthy of further thought -- perhaps in a future chapter in which I detail my visits to the other forts as well. But for now, it is simply a bit of a post-script to the other parts of my Thari journey. The rest of the ride back to Hyderabad was, for me, a rough one. This road was not smooth and straight, as the previous day’s road had been, but rather something of a ruin itself. Our intrepid driver, Hanif, had to keep constantly alert so as not to slam too riotously over the numerous speed-breakers -- and Sindhi speed-breakers are no gentle speed bumps like we know here in the States, but rather steep and pointed little walls, which Papa Saeed likes to call “car-breakers.” And apart from that, pot-holes like small canyons sank into the road at regular intervals, the results of flooding and erosion and neglect. And Hyderabad itself seemed elusive on this afternoon, because when we finally approached the city limits, we found an enormous traffic jam blocking the way completely. A long detour and second attempt met with yet another closed road, and only the third lengthy detour succeeded in delivering us all back to Inam’s house. But all in all, what tiny difficulties those were--surely not even worthy of minor grumpiness as I sat in the car. After all, I had a comfortable reclining seat to myself, in a safe if bouncy vehicle, with climate control, and kind friends as well. To quell my grumpiness, I’d have done well to remember the diligent Sassui, who braved a far longer journey in the same direction, and without any vehicle at all, and no comforts, and no companions. That legendary queen traversed her desert homeland with nothing at all to protect her, apart from the love of her heart, as she sang: “Palak’a na rahey dil to reea, waru miyan Khan Baloch….palak’a na rahey.” Photos from this episode.....

2 Comments

1. Mandir There was almost no light left as my traveling companions and I departed from the village, rumbling along that strange hilly road whose edges were now even more obscured by dust and darkness. I think we were all quiet for some minutes then, allowing the strangeness and mystery of the place to sink into us a bit longer. Or perhaps only I was quiet, sitting there in the front seat and watching the shadowy dunes drift by, while my buddies were pleasantly chatting in the back seat. The three of them, Irfan, Naz, and Khatau Jani, all squished together in that small space into one affable lump of friendliness. And I should also count our driver, Hanif, among my companions, because he was also a pleasant presence in all these various scenes that I am describing. As we left that broad wild desert terrain and reentered the narrow streets of the city, I inquired as to what we were doing next. “We are going to visit that mandir!” answered Naz. And I recalled that earlier in the day, my buddies had asked around to find out what times prayers would be offered at the Hindu temples (mandirs) in the city, and they had determined that the Shri Krishna Mandir would be holding prayers at just the right time in the evening. I cannot remember now how many mandirs there are in Mithi, though I did ask -- it was something like 8 or 10, perhaps. In any case, it needs to be a substantial number, to serve the majority Hindu community in Mithi (see my previous blog entry for a bit more on that topic).  Night barber in Mithi. Night barber in Mithi. Even in my travels in other parts of Sindh, where Hindus are a small minority, I have been given many opportunities to learn about Hindu worship in Pakistan. Eventually I will write up an account of my earlier visit to the beautiful Saadh Bello mandir in Sukkur, for example -- a golden-yellow temple that floats on a small island in the middle of the Indus. And I have also visited the shrine of Udero Lal, near Bhit Shah, where a Hindu holy site stands adjoining a Muslim shrine, connected by a small courtyard. Both of those visits deserve attention in their own right -- but I mention them now in order to make it clear that Hinduism and other minority religions too are very much alive in Pakistan, even though it is an Islamic Republic. Others may comment on the difficulty of being a member of a minority in this Islamic nation, and I do not deny those difficulties -- but another reality is just as clear to me, which is that the majority of Pakistanis respect and honor all faiths in their hearts. Most of my Muslim friends, when I ask them about these topics, answer sincerely that their own strong faith in Allah commands them also to be respectful of other faiths, and to look upon all humanity as one.  Children buying Diwali firecrackers. Children buying Diwali firecrackers. So -- this visit was not going to be my first visit to a Hindu temple in Sindh, but it would still be unique, because I had not yet witnessed any prayers or rituals inside one of these temples. There was also a special energy humming around the dimly lit streets of the city, because it was just a few days before Diwali, and the local children were buzzing around street vendors’ carts, picking out their favorite sparklers and firecrackers for the holiday. And quite a number of impatient firecrackers could be heard to go off that evening as well. Our car stopped in one of countless shadowy and bustling streets in the city of Mithi, near the Press Club, which would be our destination a little later when the inevitable need for tea would arise. From this spot we could easily walk to the mandir in question -- easily in terms of distance, though the walk was a bit harrowing to me in another sense. There is no separate place for pedestrians to walk in those narrow streets -- not here or in any typical Sindhi town. So people of all ages traveling on foot must share the path with vehicles of all sorts and moving in all possible directions -- cars, motorcycles, carts, and not a small number of wandering cows and bulls (a sacred symbol, of course, in Hindu Mithi). Of these, the only ones that I find genuinely stressful are the motorcycles, which seemed to rev about with wild abandon, squeezing themselves suddenly through tiny spaces between pedestrians. Avoiding their paths seems to be second nature to my Sindhi friends, but for me it is a rather enervating pursuit, especially in such darkness, where tripping on stationary things is also a distinct possibility. But I did my best to stay close to where my buddies were walking, and managed to get by without any unexpected tumbles or collisions. “It is useful that you are dressed locally!” Naz was saying as we dodged along the alleyway. “Yes, that was intentional,” I responded. I was wearing a very simple traditional suit that day, modest and loose-fitting, with colorful embroidery and mirrorwork. All of the Sindhi clothes that I wear are gifts that I have received from family and beloved friends, and of these, the majority are traditional in style, meaning that they are examples of Sindhi handicraft -- and not necessarily the sort of clothing that urban women in Sindh wear on a daily basis. But I’ll save the differences between those kinds of attire for some other blog post. Suffice it to say that the outfit I had chosen for that day not only disguised my Western-ness, but also my modern-ness, making me appear -- at least from a distance -- something like a local. And though the lightness of my skin always draws the attention of those who notice, there is never any hesitation among Sindhi people to accept me as one of their own, and quickly, seeing that I am comfortable in their cultural attire.  The writing above the entrance reads "Shri Krisha Mandir." The writing above the entrance reads "Shri Krisha Mandir." Along one of these dark streets, the walls opened in a high archway, through which a walkway ascended at a steep grade. This was our mandir. Up this ramping walkway was a colorful though shadowy courtyard, where we took off our shoes. It was not as dark here as on the street, however, because much light was escaping from within the mandir itself, where there was no shortage of illumination. We moved inward toward that light, ringing the hanging bell on our way. Some of my readers may be unfamiliar with Hindu temple bells -- and I am sure that there is much more symbolism in them than I am yet aware. But I can offer for the moment that it is believed that sounding the bell will wake the Gods inside and prepare them to hear your prayer. But I think there is much more meaning in these bells than that -- notions of time and peace and vibration and divinity -- which perhaps I will learn more about in the future.  Inner courtyard and bell. Inner courtyard and bell. Actually, the impressions that I can offer from that evening in the mandir are in general just as hazy and naive as my above description of the temple bells -- though I believe they are still worth sharing. I do not pretend to be an expert (about this or any other aspect of Sindh, really) -- instead, what merit my observations might have comes from the freshness of my naive perspective. Inside the mandir, there is really only one thing (apart from the highly decorative walls), and that is the central shrine. In this case, the shrine is not in the very center of the room, but not up against the far wall either -- the reason for that being, I would soon discover, that it is necessary to be able to walk behind it, and to circle all around it. The statue of the god in the shrine itself is, to the best of my understanding, the most important element of the temple. In this case, of course, it is a statue of Krishna, though in other temples you would find other gods -- the powerful Shiva, Ganesh with his elephant head, the monkey-god Hanuman, etc. And it is believed that these gods come to inhabit their statues during worship; thus offerings are made to the statues, and incense and candles lit in their honor. (Again I want to stress that my understanding of the subject is minimal, but that I know there are thousands of layers of symbolism and complexity to all this, which can be understood by those who wish to learn.) But it was a fortunate coincidence for me that the iconography of this particular temple was all devoted to Krishna and his associates, simply because Krishna happens to be the Hindu god with whom I am most familiar. Through my study of kathak dance and rudimentary knowledge of the Mahabharata, I can at least identify Krishna as the blue-skinned god of the dance, playing his flute to the delight of his love-intoxicated Gopinis (cow-herding girls); I can recognize him by his peacock feather and his bansuri (wooden flute), and I can identify the woman at his side as Radha, his partner and beloved. And these were the scenes illustrated on the walls of his mandir.  Base of the shrine. Base of the shrine. At first, my buddies and I were the only people inside the temple, apart from one or two men who seemed to be priests or caretakers of the place, and my buddies were chatting with them cordially. I think it’s worth emphasizing here again that this was a moment of genuine interfaith exchange -- because out of the four of us (Naz, Irfan, Khatau Jani, and me), only Khatau is a Hindu. My Muslim friends treat the mandir with respect and reverence, and they are just as eager to share Hindu traditions with me (their foreign Christian friend) as they are to explain their own religious customs. And for Khatau, there was clearly nothing unusual in inviting his non-Hindu friends to come to a mandir with him. There seemed to be no difference between us all; we were all part of the same human fabric. I came to realize around this point that the reason the interior of the temple was empty was that the worshippers were gathering outside and preparing to enter. Naz alerted me to this fact and I went out to watch and to record the proceedings. A small crowd of people of various ages, men children, had gathered with candles at the door of the mandir. (In my memory there were women also - but my video doesn’t reveal any. Possibly they were present but avoided my camera.) They began by ringing that bell loudly and persistently, adding also to that sound-texture repeated strikes against a small gong, and tones from a kind of a fluty whistle. Then they entered the temple and stood before the shrine, where they began to sing. It was a chant, I suppose, and not a song, but they sang it with full voices, invoking words that they all must have memorized long ago. They sang most of the lines in unison, but at key moments they broke into two-part harmony. After a few verses had past, a gentleman who seemed to be the leader came forward and received a tray with a candle from within the shrine. He swayed it in circular motions as the chant continued, and then eventually led the group in a procession around and around the shrine, all still singing, but now and again pausing from their circling walk in order to touch the small cradles that swing at the base of the shrine.

service may feel exotic to you (if you are not Hindu), I think you will still recognize some things that are familiar and common to worship in all religions: a sense of awareness of a group and a sincerity in supplication; an invocation of something very ancient; a natural pacing and rhythm of ritual -- a pace to which boisterous young children have a hard time adjusting themselves (and children are indeed the same across the globe!). 2. Lights, then Music  Naz (left) and Irfan (right) with the bookstore owners, Khatau Jani and his brother. Note the active photocopier in the background. Naz (left) and Irfan (right) with the bookstore owners, Khatau Jani and his brother. Note the active photocopier in the background. Our next destination would be the Mithi Press Club, but we stopped along the way at a brightly-lit bookshop that seemed a colorful oasis in those dark streets of the city, by virtue of its densely lined walls of brightly colored (mostly Sindhi) books. It was explained to me that this shop was owned by Khatau Jani’s family and run (I think) by his brother Kishore (if I am remembering his name right). That family connection seemed enough reason to stop in, but I soon realized that we had a more pragmatic goal to accomplish, which was to make a photocopy of my passport. The guest house where we were staying had asked for such a copy, so I had entrusted my passport to Naz earlier in the day. But photocopiers, it turns out, are a little bit hard to come by in Mithi, and that was the reason we had come specifically to this bookstore to make a copy. So that was a brief stop, and our tea in the Press Club was also brief and pleasant, and probably not worthy of further narration here. I may at some time return to the phenomenon of the “Press Club,” which seems to have a greater significance in the journalistic community in Sindh than it does in America - but that’s for another time. I will offer this shadowy photographic impression of the Mithi Press Club, however, which contains almost my entire memory of the place: This was the last that I would see of the inner city of Mithi, for this trip, anyway. It was by this point about 8:00 in the evening, which is still a bit early for dinner (by Pakistani standards, anyway). So my buddies told Hanif to drive us to a place called Gaddhi Bhit, which translates roughly to “High Dune.” A wide plateau has been leveled upon this high dune, with a big open space (seems like it would be perfect for concerts, though from what I gathered it isn’t often used that way) next to a large monument of relatively recent construction. The monument itself forms a partial wall at the edge of the mound’s plateau, intercut with archways, beyond which you can see all the lights of the city of Mithi as it lies nestled into the desert. I sat down on the floor of this arched monument for a while, looking out at the expanse in the darkness. My buddies were standing somewhere nearby, chatting pleasantly as they do. I think they are probably used to these moments when I sit slightly apart, in silence -- at least, they don’t seem bothered by it. I think they know that it is not a sign that I am moody or unhappy, but merely that I need some time to absorb everything. While I am in Sindh, I try to be like a sponge. I take in as much of that universe as I possibly can, so that I can bring it all back with me, and present it all again here in my blog, and tell the stories to anyone I meet. In these several quiet minutes, sitting cross-legged on the cool stone floor of the monument, I was not re-playing any specific episode in my mind, but simply inviting it all to sink in a bit deeper. And I was absorbing this new scene as well, the blanket of dimly glowing lights from this lovely small city below.  Drummer Boy of Gaddhi Bhit. Drummer Boy of Gaddhi Bhit. In my stillness I only gradually became aware of a rhythmic thumping sound coming from somewhere behind me, on the other side of the monument. I got up to see what it was. Around the corner I found my buddies watching a small boy with a double-skinned drum slung round his neck and long drumsticks in his hands. In that low half-light, the expressionless boy seemed to be some sort of apparition, gravely beating the two sides of his drum. My first impression was that he was all alone there, a ghost of the Gaddhi Bhit, though I think that in actuality he had some family nearby in the periphery. When he stopped playing, my buddies congratulated him and gave him a few rupees. Khatau Jani was looking at his watch, and I heard my buddies saying something about “roshni” (light), though I wasn’t sure of the rest of what they had said. “Soon the lights will come on in the city!” Naz explained to me, as we all turned our attention back out to the city view. That’s when I understood why the city streets had seemed so unusually dark to me while we were walking down below, and why the urban scene was only dimly glowing at this point. Of course there could be no other answer: load shedding. For those unfamiliar with Pakistan (and who haven’t read my other blog posts), load shedding is the result of the country’s dire electricity shortages. Most cities have to tolerate several hours per day without electricity, usually at fixed times so that you can anticipate the cut. During those hours, people have to fend for themselves, resorting to generators and large batteries. So, Mithi had been glowing dimly thus far because it was running on only auxiliary power. And now, just as Khatau predicted, all at once, the city doubled or tripled its brightness, as electricity was restored - and that dim city was dim no more. This long and eventful day is beginning to draw to a close -- but not quite yet. My buddies had told me that Thar was not only famous for its food, but also for its music -- and I had been promised a performance. Very soon after we returned to the rest house, our singer and his accompanying musicians were ready for us. The musicians set themselves up on a blanket on the floor of the large lobby of the rest house. It is typical of all traditional South Asian musicians to sit on the floor to perform, including the singers. The reasons for that performance posture probably extend back centuries and would be worthy of proper research, which I have not yet done. But I would conjecture that, in addition to practical concerns (not needing tables for the drums this way, for example), sitting on the floor emphasizes that the musicians are rendering a service, with all the humility that comes of serving. Western culture has moved towards placing its musicians on higher and higher pedestals--even though that may not be true to the spirit of the music itself. By contrast, a traditional South Asian musician assumes a posture of submission and reverence -- whether he be submitting to his esteemed audience or to his Saint or to his God -- or to all of the above at the same time. And that attitude of reverence is part of what makes Sufi music in particular so deeply affecting. In humbling himself before God, the Sufi musician somehow opens up a space in which all who listen can fall naturally into the same divine continuum--no matter what their own religious beliefs may be.  Rajab Faqeer consults his book of poetry. Rajab Faqeer consults his book of poetry. And that attitude of self-negation also goes a long way toward explaining why Sufi musicians tend to take on the word “Faqeer” into their own names. The archetypical Sufi faqeer is an ascetic and a spiritual seeker; someone who is not fed by worldly foods, but by the spirit alone. And music and poetry are part of his spiritual nourishment, which he shares with the wider world in exchange for small offerings into his beggar’s bowl. For the modern Sindhi musician, the “Faqeer” status is more symbolic than literal. A young musician these days is not expected to cast off all worldly pleasures in exchange for his art--though perhaps some of them still do, to varying degrees. The title of “Faqeer” comes now more as a philosophical concept and a symbolic link to the traditions of the past. I think this is how our singer for that evening in Mithi, whose name is Rajab Faqeer, would probably describe it himself. And our Rajab Faqeer is a young man with a round face and a trim mustache. He has a pleasant aspect from the moment you see him, but only when he begins to sing can you appreciate the full sunniness of his personality. His is a beautiful voice, which you can hear in the videos I’ve uploaded here. But I must apologize that the sound quality of my camera’s microphone does not do Rajab justice. You can get an idea of his voice, but only an idea--much of the sweetness and brightness of his tones is lost in the recording. Rajab sang in several local and regional languages, though Sindhi is his own primary language. I recorded several of his songs, but sadly was not prepared quickly enough to catch his very first number, which proved to be my favorite of the night. It was a telling of the Punjabi romance “Heer-Ranjha” by the poet Bulleh Shah. I was only barely familiar with this story at the time, and certainly couldn’t decipher the words being sung. But Naz translated the essential lines for me even as they were unfolding, so that I could understand the sentiments that go with the melodies. And these lines made quite an impression on me. The poet is using the voice of the heroine of the story, Heer, who is suffering in separation from her beloved Ranjha. And says:

But, as I mentioned, I sadly did not capture any video of that marvelous song. So I will instead share two others. The first of these contains poetry by the Punjabi Sufi poet Sultan Bahoo as well as the Sindhi poet Aijaz Ali Shah Rashdi (though the language throughout, as best I can tell, is Hindi-Urdu). It asks,

(Credit to dear Naz for the info and translation above, which I have only re-stated in my own words -- hopefully without losing the meaning or mis-stating any facts.) And the second comes from another beloved Sufi poet, Imam ul Din Dakhan, who had died only a week or two prior to this evening. It caught my ear especially because I had so recently been made aware of the poet, but also because it is a memorable tune, and because I am able to understand a refreshingly high proportion of the Urdu in this case (though by no means all of it). It is a song about the mystery and ineffability of the spirit:

And on that note of universal mystery -- I will close this second episode of my Thari travelogue…. But in the third episode, coming soon, we will finally see what desert villages look like in the harsher light of day. And now I have finally been to the desert. Only briefly, so far. Like all of my adventures in Pakistan thus far, my trip to the Thar desert in southern Sindh was a whirlwind -- fast and fleeting. Yet it created such a dense bundle of memories. Probably the best way for me to recount them is simply chronological. I will try my best. 1. Road trip We started on the road from Hyderabad, where I was staying with the family of my best buddy Inam Sheikh. Inam himself decided he needed to stay home, for various reasons, but I felt no qualms about traveling alone with two other buddies, Naz Sahito and Irfan Ansari, who likewise treat me as their beloved little sister. It took some effort to convince Papa Saeed on the phone that he could entrust me to the care of these two gentlemen, but after interviewing both of them extensively, he gave his paternal consent. And though we missed Inam’s presence on the journey, it would be hard to find two more pleasant traveling companions than Naz and Irfan. Both of them are experienced broadcasters, having attained senior positions in their fields, and yet they both radiate a childlike energy and delight that is absolutely infectious. Throughout my trips, Naz has been a keen guide for me, eagerly sharing cultural ideas with me, overflowing with information about the history and identity of Sindh. And Irfan has that kind of rare personality that can keep any gathering of friends in constant laughter. One short anecdote can illustrate this: One evening later in my trip, when I was sitting with Inam’s family over a quiet dinner, Inam answered his cell phone and started talking as usual. But soon he started laughing, and kept laughing, and pausing for a second and then laughing more. Inam’s youngest daughter and I were both soon bursting with giggles ourselves, even though we hadn’t heard any of what caused it. Meanwhile Inam kept doubling over with increased laughter while listening to his phone. I knew very quickly that the only person who could be on the other end of that phone line was Irfan Ansari.  Gas station in Badin. And why on earth didn't I turn the camera the other way to see our tea? What a shame. Gas station in Badin. And why on earth didn't I turn the camera the other way to see our tea? What a shame. So my journey was guaranteed to be a pleasant one. And my companions were further ideal for this trip because of their connections to the region. Irfan was recently appointed the station manager of Radio Mithi -- Mithi being the city toward which we were headed, which is something like a capital city to the region of Thar (in more official terms, it is the headquarter city of the Tharparkar District). So, these days Irfan is very accustomed to the four-hour commute between Hyderabad (where his family still lives) and Mithi, and was well-situated to host us at our destination. Naz too has strong ties to Thar, from his career in journalism. He recounted how he used to come to report on the difficult situations in that desert region a couple decades back, before there were even proper roads connecting the major towns. Back then, he told me, all travel was done on rough and dusty tracks. The only options were open jeeps and camel caravans. I can only imagine what it must have been like for my buddy to traverse that terrain -- in sizzling summer heat -- as a young reporter in the field. Nowadays, due to much more recent development of the city of Mithi in particular, there is a very fine new road that runs between the city of Badin and the inner desert. And as for us travelers, we paused there in Badin at a gas station, because, having already been in the car for a couple of hours, we naturally started wanting some tea! And for my Sindhi friends, this is the most normal and routine thing in the world -- but I think that my American readers will share my delight at the quaint idea of drinking tea at a gas station. As we got out of the car, I heard one of my companions saying something like “kursiyoon rakho” -- bring chairs. After a moment, some plastic chairs and a small coffee table had been produced for us -- right there on the ground next to the gas pumps. And after a few minutes more, there was our tea -- genuine mixed milk tea, served properly with china cups and saucers. At this point my Sindhi readers will be wondering why on earth I have devoted a whole paragraph to such an ordinary activity -- but I do think it’s an important observation, because this ordinary activity is practically inconceivable in America, where consumer culture and frenzied schedules have left us with little option other than the profoundly unsociable drive-thru. As we piled back into the car, the driver told my buddies (who then translated it for me) that I had been recognized. Apparently, someone working inside the gas station and noticed me, and had told the driver, “I know her! That is Miss Emily from Facebook.” This was again amazing to me -- and flattering for sure -- that I have become well enough known in Sindh that people who happen to see me are able to identify me. And how right this fellow was -- “Miss Emily from Facebook.” For what other place could more properly claim to be my permanent residence?  Gateway to Tharparkar. Gateway to Tharparkar. But now I shall delay no longer on the arrival into the desert. And it is not difficult to mark that arrival, because there is in fact a large gate positioned over the road that tells you in no uncertain terms that you have now, indeed, arrived at the desert. Of course, nature is not quite so obedient -- there is no magic line beyond which the coastal terrain turns suddenly into an expanse of sand. Much of Sindhi terrain has hints of desert anyway, even outside of Thar; and Thar itself not a land of enormous barren sand dunes like we might picture from Lawrence of Arabia. But there is still a noticeable and quick transition into the Thari landscape soon after passing through that arched gateway. And how to describe the Thari landscape! Of course, it must look quite different, at different times of year… and I was visiting it at the mildest of times, long after the blistering summer had died down. The Thari sun in November is a purely welcoming sun. The breeze is soft and sweet. And yes, there is sand -- lots of sand -- as much as one could want in a desert. But there is also a strange fertility in this sand. I might have expected sweeping sand dunes of towering lifelessness -- but in fact it would have been hard to locate a patch of empty sand larger than a few meters. Because everywhere, interrupting the sandiness, there grow an array of bushy plants and trees of almost comical appearance. They don’t give the impression of a forest -- they do not merge to form a wood. Each one of these peculiar bushy plants stands on its own, like a prickly creature who is not a complete rebel, but likes to maintain his own space. Someday I will try to learn what all these strange plants actually were…. for now I am thinking of them simply as the prickly bushes of Thar. After passing through the gate to Tharparkar, the drive rest of the drive to Mithi was only an hour or two. There is more desert beyond Mithi -- deeper desert, I am given to understand, where perhaps I would find some of those imagined towering sand dunes. But this journey did not extend past Mithi… which is where my traveling companions and I are arriving at this point of my story. There is a dense urban center of Mithi, as there is in any long-established town. But at first I was not taken there, as we rode instead along wider, government-built roads and past walled structures of a more recent vintage. [Here I am recalling information from what I learned there, which may not be entirely accurate -- any reader who wishes to supply better information is welcome to let me know, and I will edit.] I believe that Mithi has become a favored place in very recent years, something akin to a resort town, and government structures and official protocols have been developing in the area, along with a variety of different rest houses and accommodations. Irfan’s radio station is located in these outskirts of the city, and so was the guest house where Naz and I were to spend the night (in separate rooms, needless to say). 2. Radio Mithi But our first port of call was Irfan’s office at Radio Mithi. And I was quite amused to enter this space alongside my buddy Irfan, and see him in his official, leadership role. He sat down behind his large and empty desk, and almost immediately some staff person walked in with a stack of papers requiring his signature. As he examined them and applied the appropriate strokes of his pen, with a serious expression befitting a station boss, various others of his subordinates gathered around the office, waiting for his attention. Eventually, when all pressing business matters had been attended to, I told Irfan and the others that it was really quite amusing for me to see him for the first time in his Big Boss role. “Because generally,” I explained for the benefit of the others in the room, “ddingo chhokro aa!” (He’s a bit of a rascally boy.) And, hearing this, Irfan again burst into his characteristic laughter.  A Thari feast brought to the office. A Thari feast brought to the office. Around this time I learned that Mithi and Thar more broadly are famous for two things: food and music. The latter item would be demonstrated to me a little later on -- but it was already time to discover the first. I had not been expecting any elaborate spread for our lunch -- but actually, I should have been expecting it, because Sindhi meals in my experience are almost always elaborate, always consisting of more and more plates and dishes and flavors than I would have expected. Now, I must confess that I am not an avid food writer -- and although it was all delicious, I have little eagerness to go into detail about the marvelous interplay of spices, the different varieties of roti, the new twists on familiar curries that were suddenly spread before me. But I will mention my favorite part of it, a simple, paired delicacy that I have also enjoyed elsewhere in Sindh, and which will always have its own unique flavor wherever it comes from. This delightful pair of things is nothing other than butter and honey -- “makan’u maaki” as I learned to say in Sindhi. It was a fresh, rich, enticing butter (makan’u), and a honey (maaki) of indescribable depths. I am sure that I could never grow tired of the makan’u-maaki of Thar, even if I were given it every day. Naz and Irfan were also enjoying their meal with typical gusto and appreciation, even though this sort of elaborate spread is not at all unusual to them. Naz seemed particularly pleased that I was also eating with relative gusto, and conveyed my compliments to Irfan’s chef, Mustafa. I mention his name now, because he will reappear a bit later in this story. Mustafa seemed pleased and urged forward to make sure that I had gotten as much of everything as I could possibly want. Ah, one other thing about this meal is worthy of note, which is that its curries contained a lot of meat. In itself that is not notable at all -- Pakistanis are mostly Muslims, and mostly meat-eaters, and that suits my own tastes as well. But Mithi is unlike other Pakistani towns, in that Muslims are not in the majority, but rather significantly in the minority. According to one statistic I read, Mithi’s population is 80% Hindu. So when Irfan invited his engineer, Dileep Aamer, to have some lunch, Dileep at first shrugged and gestured to the meat, and said he couldn’t. Fortunately there were a few dishes on the table that were meatless (some daal and some rice, and of course the makan’u - maaki), so he did find enough to eat after all. The religious demographics are not all that distinguishes Thar from the rest of Sindh. In many ways it feels like a completely different province--so different, in fact, that many Thari people do not think of themselves as Sindhi at all. The local language is not Sindhi, but rather Dhatki -- and although Dhatki belongs to the same enormous category of Indo-Aryan languages that also includes Sindhi, I think there is enough difference between them that they are not mutually comprehensible. So, although Sindhi is widely spoken within the boundaries of Mithi, it becomes quickly less familiar in the outer desert communities, where the language is Dhatki and the lifestyle is Rajasthani. Culturally, the Thar desert is continuous with the Indian region of Rajasthan -- the border of Pakistan and India having been placed in the middle of this territory only recently in history. These were all things that I was learning from Naz, Irfan, and now also Dileep, as we finished up our meal.  Before we set out again, Irfan gave me a tour of the radio station. My readers may not know that I also have worked briefly in radio, for a few of years (though very much part-time) serving as a production assistant for a live radio program at WHYY-FM, Philadelphia’s public broadcasting station. So I was particularly interested to see how Irfan’s station operations compared to what I was used to. I don’t think that Irfan will mind my saying that it is a rather humble building: only one studio and control booth on one side of the complex and simple hallway with a few offices on the other side, connected by a small and sun-soaked exterior courtyard. But despite its tininess, Radio Mithi does contain all the life and spark that is necessary to keep a broadcasting station vibrant. We met one of Irfan’s news reporters (or perhaps there is only one of them?) as we passed by the tiny room marked “News Section.” In the technical part of the building, I was shown the transmitter room, which contains only a few boxy-looking machines, and yet is responsible for keeping that radio signal alive and well. Next to that was the control booth, containing an old-fashioned fader board (but I must note that old-fashioned is not a bad thing when it comes to audio technology, because in many cases audio devices used to be made far more solidly and elegantly than they are today) as well as a computer interface for airing content that isn’t being immediately produced in the neighboring studio. On the other side of the glass, in the aforementioned studio, a young man was reading in Dhatki from a script in front of him. I must admit that I have absolutely no idea what the content of this program was--presumably some information of local interest, though I believe poetry was also involved. I can say that the young man displayed admirable focus on his task, because he must have been surprised to see his station director appear on the other side of the glass along with a host of others (for a group of people had gathered along with us, as always happens when I am shown around any facility), including an obviously foreign female. A look of nervousness did appear in his eyes, but you would not have been able to hear it in his voice as he continued his narration. After a moment, Dileep signalled him to stop, and used the computer interface to switch the program to some music (which is probably also a very typical part of this broadcast), and we all barged in on the poor radio announcer in his studio, and took the photos that you see here. As we left, I told the announcer that he was doing a very good job -- though I don’t know if he could understand me. Because of my previous job, I’ve spent a lot of time in radio control booths, and radio listening (in the form of the BBC) is still an extremely important part of my life, so I was interested to compare what I found in Mithi to what I’ve known before. My former workplace, although desperately underfunded by American standards (because our public broadcasting is funding in the majority by free will donations from its small listenership), nonetheless had a beautifully renovated building, full of what now seems to me to have been very shiny new equipment. The equipment available at Radio Mithi is, by comparison, extremely minimal. However, the population of Mithi is also minute in comparison to Philadelphia, so any comparison of the two radio stations is difficult to achieve meaningfully. It would not be as difficult, however, to compare the roles and effectiveness of the two countries’ public broadcasting systems on the whole -- and I am tempted to start doing that here -- but I sense that my readers might be quite eager at this point to get on to the more picturesque aspects of this Thari voyage, which are still to come, in great abundance. So for now I will simply say that it seems to me that Radio Pakistan on the whole, despite a lack of up-to-date resources, is nonetheless a varied and integral part of the broadcasting life of the country, and that it is more appreciated and far more alive than its American counterpart. It is also more essential in Pakistan, a country in which dozens of languages are spoken by regional communities, and in which the nation’s official languages (Urdu and English) cannot be expected to communicate deeply with the entire population. Programs at Radio Mithi go out in both Sindhi and Dhatki (though perhaps some programs are carried from higher-up station affiliates in Urdu). In a country that is so linguistically diverse, surely radio must be a crucial way of keeping citizens connected, in a way that Americans can hardly fathom. But now I shall speed up the tape a little so that we can finally get outside and into the desert. Our next destination was actually our guest house, where I was given quite a large and elegant room to myself. Naz took the room next to it (and only later did I see how much smaller his room was), wanting to make sure that I felt safe, with someone I knew close at hand at all times. After the requisite settling into these rooms, and of course, some tea (served out in the lobby area), the afternoon had already advanced considerably. It was past four o’clock, and the sun was falling low in the sky. Seeing this, I got a bit panicky, knowing that there was very little time left for good photography before night would fall. So I urged my buddies back into our vehicle so we could head towards what I most wanted to see: a true Thari village. 3 - Dry Venice, and a City made of Pottery On our way to this village, however, I also got my only decent glimpse of the inner city of Mithi. And I wish I had had time to take photographs (at the time I didn’t want to waste the sunlight, so didn’t ask to stop the car), because it is fascinating to look at. Though buildings seemed to be made of similar materials and on similar patterns to others that I have known in Pakistan, they all seemed to be a bit smaller and a bit more delicate, a bit more ornate, more intricately interwoven with one another. The impression I got was something similar to Venice -- a city which is certainly a part of Italy and yet feels at a deep level intensely different; more luxurious without being richer, more ornate without being more ostentatious, and somehow possessing a very different imagination from its wider context. My companions were surprised at my naming of Mithi as the “Dry Venice,” but I think that they were nonetheless convinced by it when I explained.  Our local guide, trying his best to get his bike moving, as the sunset rapidly approaches. Our local guide, trying his best to get his bike moving, as the sunset rapidly approaches. At one point, in one of these dusty and decorative streets, the car stopped for just long enough to allow another gentleman to climb into the back seat of our car, where Irfan and Naz were already sitting. This was Khatau Jani, a new face and name for me, but an old friend of both my traveling buddies, a fellow journalist and a native of Mithi. He is a pleasant, quiet fellow with curly hair and a slim physique, and he became my third traveling buddy for the rest of this short trip. Khatau had arranged for someone belonging to one of the local villages to guide us out of the city, which I only realized as I noticed that we had begun following this person on his motorcycle. And the process of actually reaching the village was prolonged yet more because our motorcyclist was also having difficulty getting his vehicle to move. By the time we reached this village, the sun had just fully set, so my entire visit to this extraordinary place was colored in the strange shades of twilight. The low light levels made photography a bit difficult, but the experience was magical. Though I cannot ignore the extreme poverty of the people who live in these villages -- their lives are full of harsh realities that are obscured by the gentle mistiness of this twilight -- I also feel called to celebrate the beauty of these people and their surroundings and their simple way of life. Because what I saw in this brief visit was so beautiful as scarcely to be believed. The village seems to grow organically out of its peculiar terrain, which is a sloping hillside of sand dune, dotted with those same comical bushy plants as I mentioned earlier. At this time of evening, sky and sand merge into the same color, and there seems to be no clear border between the grainy, unsolid ground and the dust-clouded sky. Shadows also are gentle and nebulous, having no edge or form. And on this blurry canvas arises a series of walls and huts and courtyards that seems to have come out of a fairy tale. The phrase “mud hut” might accurately describe these houses on one level, but those dull-sounding words do not convey the fineness of the structures. They do not seem to me to be “mud” but rather pottery. The village seems sculpted of a soft sandy clay; all edges are smoothed and rounded by the atmosphere, and yet all the architectural lines are clean and pure. The mud-village and the sand and the sky are all one single color and entity, varying only in degrees of solidity and contour.  A rare glance from behind the veil. A rare glance from behind the veil. And on top of that mesmerizingly colorless structure is laid so much color -- in the form of rillies (traditional quilts) lying on wooden cots in the courtyards and in the colors of the women’s dresses and long veils, which they typically hold up in such a way as to hide their faces completely from view. And the other source of color are the fabled peacocks, which run and dance in the wild here, and in great numbers. Who can describe the sight of a peacock strolling through its native land with such confidence? My camera has failed to do it justice, and my words will fail as well.  The hidden gaze. The hidden gaze. But the women who walk through the villages of Thar are just as beautiful as the peacocks, and just as colorful. I actually give credit to these women for inspiring me to learn about Sindh in the very beginning -- they are in some ways the reason that my whole adventure began. (Explanation for that can be seen HERE.) The Thari women have a rare kind of beauty, a royal and elegant quality that comes not from wealth or status, but somehow radiates from their inner humanity. They have a strength and a worldliness in their bearing, and a feminine grace that refuses to be dimmed by the harshness of their deprivation. They wear long dresses of the brightest colors, and long veils that often descend to their ankles. The dresses are often sleeveless, but their arms are never bare: they are instead covered by thick white bangles. Modesty is extremely important to these women, who rarely show their faces -- a rule which applies not only to strangers but even to men in their near-immediate family. It was explained to me at one point, for example, that the reason a particular woman was holding her veil over her face with left hand was that her father-in-law was presently standing somewhere to her left, and even he was not supposed to see her. Similarly, passing women typically covered their faces even from my view. But I was never made to feel alien among these beautiful people. The villagers welcomed us warmly as their guests, and if I seemed a strange creature to them, they certainly didn’t reveal it. I was delighted to be invited into one of the huts, the domain of the young wife of a man who was speaking with my travel buddies. This woman gestured for me to come in and sit down, first spreading a thick quilt for me to sit on. And she was one of these fine Thari beauties that I had long expected -- a pure and natural radiance veiled in deep colors. I am grateful that she allowed me to take her photograph. She was hesitant in this, but when her husband gave permission, she allowed me a quick smile to catch her beauty and share it in this gentle way with you all. She and I couldn’t speak a word together -- a Dhatki speaker, she couldn’t understand my still-terrible Sindhi. So I spent these few moments simply in observation, trying to absorb my surroundings and imagine what her life must be like. The hut was maybe fifteen feet in diameter, with very little inside except for cooking pots and a rustic stove, on which something or other was simmering.  Small world inside a Thari hut. Small world inside a Thari hut. There was a basket of fruits there which seem to be a local delicacy -- I can’t name them -- but can recognize them now by their faintly putrid smell. And there was a pile of mats for sitting, and little else. After a minute or two, an older woman, probably the mother of the young wife, came in and tended to the stove. But despite this fascinating glimpse inside the home, I am still largely at a loss to imagine what the rest of their lives must look like. When I re-emerged from the hut, I found my buddies talking with a large group of men gathered in the courtyard around a large quilt that had been laid on the ground. “Come, sit sit!” Naz called to me, and pointed to the quilt. The men all moved a few steps away from it, keeping a respectable distance as I took off my shoes and folded my legs into a sitting position there, not sure what was going to happen.  “They would like to offer you peacock feathers!” Naz explained. And sure enough, there was a man holding a large bundle of those bright feathers, fanning out in all directions like a full tail of the peacock itself. And he proceeded to hand me the entire bundle. I handed my camera to Irfan so that he could take pictures of the beautiful gift. We didn’t actually take all of them with us, but only a small handful -- and what happened to that handful, I’m afraid I do not know. As a result, it feels a bit like these feathers might not even exist outside of that village -- like objects in fantasy stories that instantly vanish when you take them away from their enchanted place of origin, the only place they belong. The feathers were real enough -- I held them softly against my face -- but only there in Thar. It was too short a visit to take in even a small fraction of what was going on around me in that village, though I kept my camera in hand to catch details that my eyes could not notice. Children gathered around, which is always one of my favorite parts of village visits in Sindh -- the children always follow their curiosity and stay as near to me as they can. My photos reveal to me that there were a couple of children in particular who stayed close by, like small curious angels -- a gentle-looking boy in an olive-colored shalwar and a girl with a quizzical expression and a lime-green veil. If I ever get a chance to return, I'll try to find them and ask their names. Evening was growing darker, and soon we were again on our way…. I will stop my narrative here for the moment, but soon will follow up with Part 2, in which there is much more to come…. Mithi at night, sung prayers in a Hindu temple, a different village in the light of day…. for now, wari milandaseen, dosto. complete photo gallery for Thar: Part 1 .... “SWEET EM! YOU ARE GOING TO HAVE THE TIME OF YOUR LIFE,” said Papa Saeed into the phone. I was still in Hyderabad, scurrying to get myself put together to go on the day’s field trip. I had just told Papa that Inam and buddies would be taking me to see Makli and Thatta, which are neighboring towns about two hours southwest of Hyderabad. “YOU WILL BE AMAZED AT THE HISTORIC SITES. YOU HAVE NEVER SEEN ANYTHING LIKE MAKLI. TAKE MANY PHOTOGRAPHS, SWEET EM.” This was the second full day of my second trip to Sindh. My previous two blog entries describe most of the first day -- my welcome in Hyderabad by my dear friend Inam Sheikh and his family, the assembling of buddies, our visits to sites within the city of Hyderabad -- but even they do not describe all that had already happened since my arrival. On that first night, for example, I was honored with a gathering of extraordinary Sindhis who met me for dinner at the Hyderabad Gymkhanna, organized by the prominent intellectuals--whom I am proud to call my friends--Jami Chandio and Sahar Gul (who is Jami’s wife, but also a highly respected academic in her own right). Jami and Sahar had gathered a room full of Sindhi luminaries to meet me--men and women in equal number--writers, anthropologists, psychologists, activists, journalists, and others, including my dear adi (sister) Shagufta Shah, who had also greeted Andrew and me on our first day in Sindh on the previous trip. I wish I had recorded the proceedings as these guests introduced themselves to me one by one around the room. Rarely have I been in such thoroughly distinguished company -- each one of them far more accomplished than I. Each day I spent in Sindh seems to have been stuffed with several lifetimes’ worth of experiences, which expand across many pages when I try to unravel them for this blog. But now I shall move on to that second day of the second trip. After having breakfast with Inam’s wife and daughters, who are themselves so charming that I could have happily spent the whole morning chatting with them, Inam told me that a few of our buddies from the previous day had again gathered and were ready to depart. I think there were five of us -- Naranjan, Rafiq Chandio, Mohammad Khoso, Inam, and myself, plus a guard and maybe another driver, and we would be joined by several more buddies in the afternoon at Thatta.  Our first stop: a mysterious terrain. Our first stop: a mysterious terrain. We left Inam’s house in two cars, and for the first leg of the journey, and conversation was lively, such that I almost didn’t notice when we suddenly stopped in an unusual expanse of desert-like terrain. And I am not entirely sure what this place was. I think it was an enormous burial ground--it certainly looked like that--but it looked to me like something from another planet, with its strangely arranged jagged stones, organized and yet seemingly organic, like the stones had arranged themselves there on their own. The whole place been both immensely eroded by the sands and winds of time, as well as oddly compacted onto itself, its obelisks and memorials all gathering closer and closer to one another like a contracting galaxy of stars. If this place was explained to me at the time, I can’t recall the story -- perhaps Inam can fill us in on this, if he reads this blog entry. Or perhaps it is more charming to remember it as a mysterious alien graveyard. But that was only a quick stop on the way--it was not the main destination. After the requisite photo-taking, we buddies re-shuffled our car arrangement and continued on toward Makli. This place towards which we were headed was also a graveyard, and also a ruin, but something on a very different scale from this first wasteland. Inam did try to explain to me, in vague terms, what we were going to see. But I suspect I still had little concept of what it was until we actually arrived at the Makli Necropolis. True to its name, this is not merely a graveyard, but a “city of the dead” (necro+polis), and one of the largest of these in the world. It is a silent city, consisting of miles of tombs and monuments erected in the memory of countless rulers and nobles and saints of Sindh. By some estimates there are as many as half a million graves, though of course not all of them are grand mausoleums. Nonetheless, there are many mausoleums, grand and grander, old and older, in varying states of erosion under the Sindhi sun. Researching the site after the fact, I found this little gem of a paragraph in a BBC travelogue, which I think bears sharing here: